Tap or click the button below to download an activity booklet to color your own anemone or draw your own Long Island Sound animal from the #DontTrashLISound Protect Our Wildlife series.

Learn About the Habitats on Long Island Sound’s Seafloor!

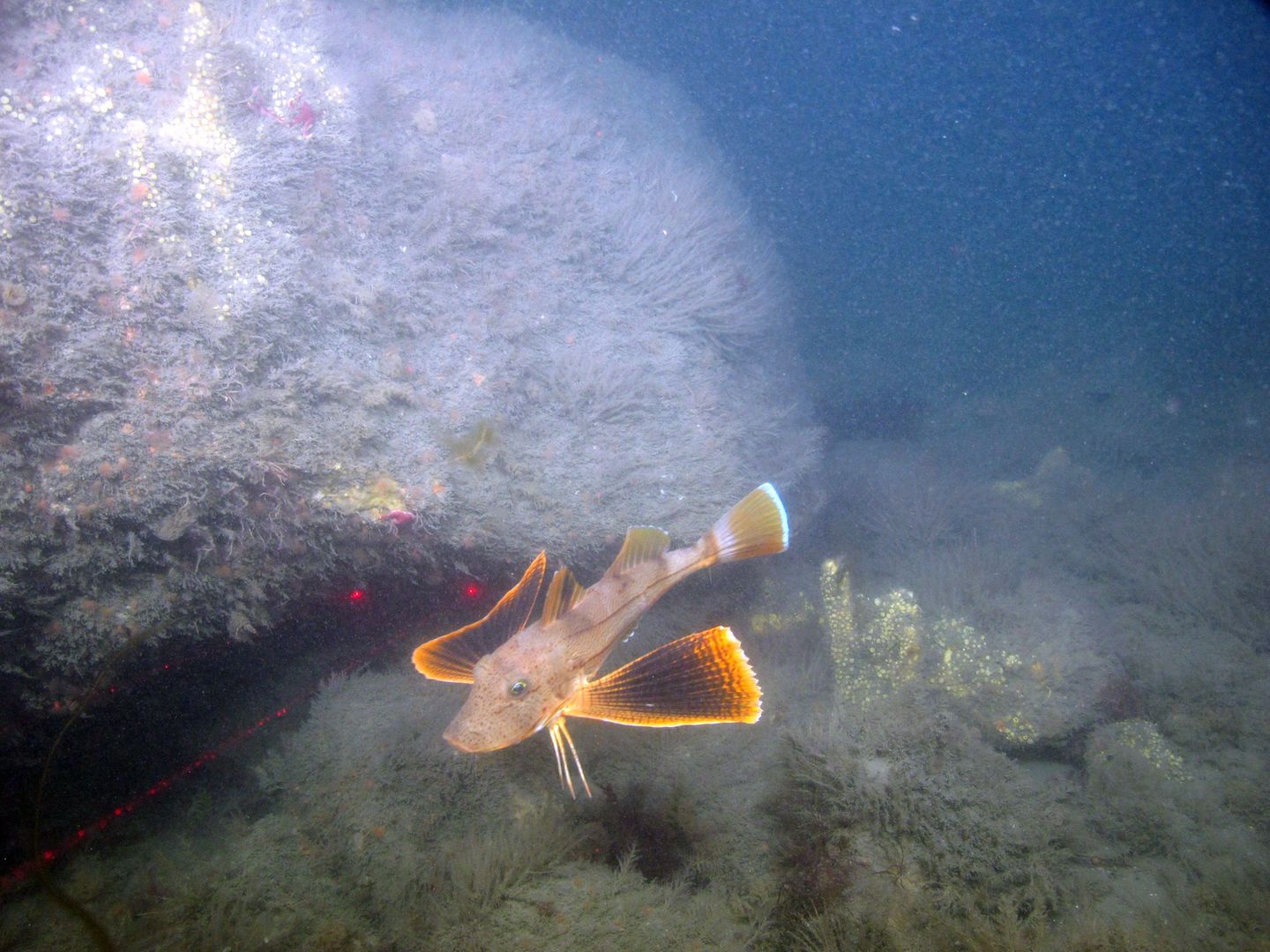

Life Under the Surface: Scientists map undersea life of the Sound

From shallow sandy habitats to deep boulder habitats, life for Long Island Sound’s marine life is rich in diversity. Long Island Sound’s undersea Habitat Mapping Initiative, with funding that was administered through the Long Island Sound Study, is documenting this life in images and maps on its website where you can see for yourself with an Underwater Story Map.

Tap or click the button below to download an activity booklet to color your own squid or draw your own Long Island Sound animal from the #DontTrashLISound Protect Our Wildlife series.

Facts About the Longfin Squid: one of Long Island Sound’s Most Abundant Invertabrates

Many people are unaware that longfin squid (Doryteuthis pealei) are very common in Long Island Sound. In fact they are one of the most common invertebrate species, by weight, caught in the Long Island Sound Trawl Survey (for a slideshow of the Long Island Sound Trawl Survey (LISTS) see: www.ct.gov/dep/lib/dep/fishing/fisheries_management/trawl_show.pdf ). Squid have been one of the top three invertebrate species caught in the Survey for twenty-six out of the last twenty-eight years. They also comprise a major component to the Sounds forage base for popular sport fish caught by anglers such as striped bass and bluefish. Long-finned squid typically migrate into the Sound in May to feed and spawn and then move back out to the warmer continental shelf waters in the late fall. Squid are in the mollusca phylum and are actually related to clams, oysters and other bivalves; however, squid have an internal shell called a pen rather than the external protective shell of these other molluscans.

Squid have a unique life history and have unique morphological characteristics that set them apart from other invertebrates. Squid grow extremely fast and only live about nine months to a year. Most squid in the Sound are less than a foot long (mantel length) but some have been recorded up to 16”. The larger mature squid show up first in our waters followed by smaller immature individuals. Although squid are known to spawn year round, the majority of squid in the Sound spawn in May through August. The Long Island Sound Trawl Survey (LISTS) will catch clusters of egg capsules, or “egg mops”, which are often laid on some sort of object like fucus (a common alga in the Sound) or other solid object on the bottom. Squid are social spawners, so each one of these egg mops may be comprised of hundreds of egg capsules from several female squid. Egg mops caught in LISTS are typically less than 1 foot in diameter; however, other parts of the northeast have recorded clusters as large as two to three feet in diameter. Within two to three weeks, depending on water temperature, the eggs will hatch and by mid to late September LISTS Fall Survey will often see young squid from 3 to 9 centimeters in mantel length (or 1 to 3 inches long). LISTS largest catch during a fall survey was over 5,800 squid in a single 30 minute tow. In some years where squid are particularly abundant the survey has actually averaged upwards to 270 squid per tow.

One of the most fascinating things about long-finned squid is their ability to change color and the patterns of their skin. Like other cephalopods, including octopus, they are often described as the “masters of camouflage”. They have the ability of using their well studied nervous system to control the underlying skin cells to change their color. Squid can selectively control reflecting cells called leucophores and chromatophores which are organs that contain different types of pigment that result in a wide array of varying iridescence. Looking closely at the surface of the skin one can see many small dots which are the chromatophores. Different colored chromatophores are controlled by muscles which relax or contract to form the overall shape and color pattern.

Although long-finned squid inhabit Long Island Sound, there hasn’t been much of a directed fishery on them in several years. However, landings in Connecticut have been increasing since 2009, with most of the Connecticut commercial vessels directing their efforts south of Block Island and Long Island, New York. Average landings in Connecticut in recent years has been about 1.5 million pounds. In 2019, the commercial fishery had landed a record harvest with over 2.2 million pounds worth an estimated 2.8 million dollars. Long Island Sound is relatively only a small portion of the squid’s geographical range, which extends from Newfoundland to the Gulf of Venezuela, but it is a very important nursery area where the species can flourish.

The article was written by Kurt Gottschall of CT DEEP’s Fisheries Division.

“Well, this is good news! Thank you Suffolk County Legislature for approving a bill to discourage the improper disposal of Personal Protective Equipment. Protect #LISound. Stop #PPElitter and #DontTrashLISound. http://ow.ly/PwTH50AGD5B

Eight Million Metric Tons! That’s about how much plastic enters our oceans each year! Bottles, bags, take-out containers, and fishing lines to name a few items. This is why the Long Island Sound Study this week is kicking off its fourth annual summer #DontTrashLISound campaign, to educate #LISound residents about the dangers of plastic to wildlife, and about what we can do to help make the Sound Trash Free!

The campaign, scheduled to run through early September, will include messages on social media on what people can do to promote trash-free beaches and Long Island Sound, such as by reducing their use of disposable plastic bags and bottles. There also will be quizzes on Instagram to test the public’s knowledge on plastic’s impact on oceans, and posts about the Covid-19 related problem of disposable gloves, masks, and other Personal Protective Equipment. Continuing this summer will be the popular Protect Our Wildlife stickers series that encourages residents to put a sticker highlighting a Long Island Sound animal on their reusable bottle and take a selfie at a Long Island Sound beach or park.

About three or four messages will be posted each week during the campaign. Long Island Sound’s Citizens Advisory Committee will help spread the messages by sharing the posts on their own social media sites.

So please, #DontTrashLISound. Break the Single-Use Plastic Habit! Use reusable bags and bottles at the beach and your local park. And discard #PPElitter in a secure trash can. Learn more at www.DontTrashLISound.net and view the posts on LISS’s Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram sites.

Each year the Long Island Sound Study develops a Work Plan as part of the National Estuary Program that outlines the work being done with EPA funds to help achieve the goals of the Study’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan. The 2020 Work Plan describes LISS activities planned with 2020 federal funding for Oct. 1, 2020 to Sept. 30, 2021. It also highlights projects undertaken from Oct. 1, 2019 to Sept. 30, 2020 with 2019 federal fiscal funds.

Download LISS FY2020 NEP Work Plan to read the document.

“Everything is connected – plants, land use and waterways…what we do matters – what we do on an individual level.”

Judy Preston, Long Island Sound Study Connecticut Outreach Coordinator

Since 2013, Judy Preston, the Long Island Sound Study Connecticut Outreach Coordinator through Connecticut Sea Grant, has taught hundreds of gardeners a better way to plant for their yards and Long Island Sound. Through her Coastal Certificate program, Preston teaches how to add native plants and grasses to a garden to reduce the need to use pesticides and fertilizer, chemicals that can enter local streams, and eventually do harm to the Sound and its aquatic life. Native plants also provide habitats for birds, bees, butterflies, and other creatures.

Preston has conducted eight Coastal Certificate Programs since 2013, and as part of obtaining the certificate, her students have delivered more than 2,000 hours of volunteer community projects. Unfortunately, the final two classes of this year’s program, which was being held at Connecticut College in March, were delayed as a result of the pandemic. But you can read about some of the past work from an article that appeared in the winter 2019-2020 issue of Wrack Lines, CT Sea Grant’s magazine.

Maggie Redfern, the assistant director of the Connecticut College Arboretum, joined Gardening for Good host Judy Preston recently to discuss what you can see while practicing proper social distance at the Arboretum. The Arboretum is a special place to enjoy native plant gardens, trails, and Long Island Sound coastal habitats such as Mamacoke Island.

Connecticut Sea Grant’s Judy Preston, who is the Long Island Sound Study Outreach Coordinator for Connecticut, is on the air and on online streaming! Judy is the host of a new radio show on the iCRV internet radio station in the CT River Valley. The “Gardening for Good” show strives to make connections between good gardening practices and protecting local streams and Long Island Sound.

Horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus, are unique and amazing creatures. They thrived on Earth’s shores and waters more than 450 million years ago – before dinosaurs appeared – and they are still around today! They can be found in Long Island Sound and along its shoreline!

In learning about the horseshoe crab, it’s good to first know about two common misconceptions. First, horseshoe crabs are not actually crabs, such as fiddler crabs or blue crabs, which are crustaceans. Rather, they are more closely related to arachnids, such as spiders and scorpions. Secondly, despite their strange brown helmets and long spikey tails that make them look kind of threatening, they are harmless. The telson, or spiked tail, that some people are afraid of is simply used to help the animal right itself when it’s upside down.

A Peek Underneath

Underneath the exoskeleton, which is a shell that resembles a horseshoe, are six paired appendages that are used for eating and locomotion. Horseshoe crabs don’t have jaws to chew food. Rather, when the five pairs of appendages that act as legs are moving, the bristly areas at the base of each leg called gnathobases tear and shred clams, worms, and other invertebrates. The other pair of appendages, two tiny front pincer claws called chelicera, push the food into their mouths, which is at the center of the legs. Young crabs also molt their outer shells as they grow, so you may find their empty shells during a beach walk. Closer to the horseshoe crab’s tail,or telson, are gills that resemble the pages of a book. These are called book gills and they are also used for propulsion to swim. (Larger photos with labels of the horseshoe crab’s anatomy can be seen in a slide show in the media center of the Long Island Sound Study media center).

Horseshoe Crabs are a Vital Part of the Ecosystem

For most of the year, horseshoe crabs move and feed along the seafloor. Paired female and males come ashore in the spring, mid-May through June in Connecticut and New York, to spawn. They follow the high tides up the beach both day and night but are most abundant during the evening high tides of the new and full moons. The larger females will dig nests 20cm deep (about 8 inches) on the beach close to mean tide, depositing about 10,000 small green eggs that are then fertilized by the male while they are covered with water. The paired female and males then follow the receding tide back out to sea. These eggs are an important source of food for migratory shorebirds, including red knots, ruddy turnstones, sandpipers, plovers, and dowitchers. This food source is only available when horseshoe crabs are abundant and dig up each other’s nests. Connecticut’s and New York’s horseshoe crab population is too low for this resource to be available to shorebirds.

HITCHING A RIDE

On a beach walk in the spring, you might find many small animals that have hitched a ride on a horseshoe crab’s shell. Horseshoe crabs have been called “walking hotels”—barnacles, bryozoa, slipper shells, sponges, and flatworms are some of the animals that attach themselves to their shells. Photo by Richard Howard.

Blue Blood and Many Eyes: The Horseshoe Crabs Importance to Human Health

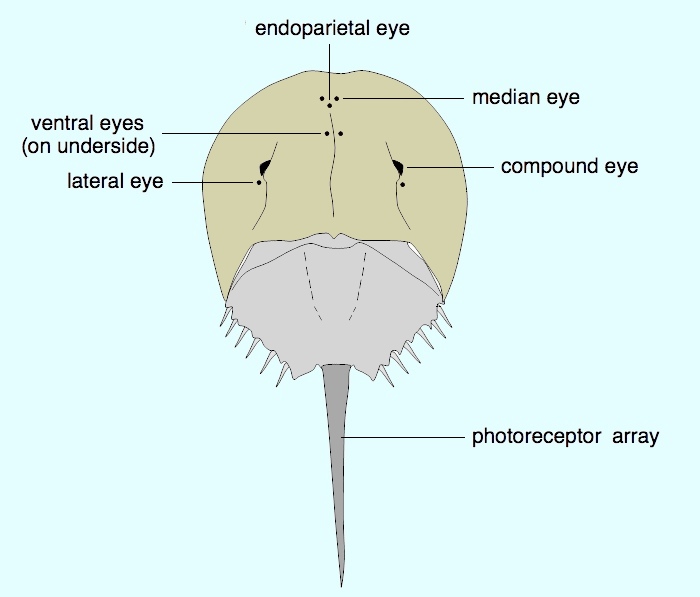

These amazing creatures also have ten eyes! The two compound lateral eyes of horseshoe crabs are used to help them find mates. The other ‘eyes’ contain over 1,000 photoreceptors, which have been studied by vision researchers to get a better understanding of human vision. Horseshoe crabs also have another unique feature of its anatomy: their blue blood, which is due to copper-based hemocyanin. Their blood also contains a product called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) that is harvested and used to identify the presence of harmful bacterial toxins in vaccines and other medical devices. No synthetic equivalent that has been federally approved for use is available to date. Pharmaceutical labs try not to kill the crabs when blood is extracted for medical use, but unfortunately, not all survive.

Besides medical purposes, horseshoe crabs have another important use for humans: they are harvested by fishermen for bait, and used to capture eel and whelk.

An Ancient Species, but Now Under Threat in Long Island Sound

Horseshoe crabs have survived five major mass extinction events over our earth’s geological history, and the species is known as a ‘living fossil’ because its basic body shape has changed very little over time. But now, with recent population declines in Long Island Sound, their very survival in our region is challenged.

Population monitoring data collected by researchers and citizen scientists, including tagging and spawning counts by Project Limulus based at Sacred Heart University, show that the numbers of horseshoe crabs in Long Island Sound have steadily declined over the past 20 years. Overharvesting, habitat loss, pollution, bycatch in abandoned “ghost nets” and lobster traps, and motorized vehicles on beaches, threaten their continued existence. Dr. Jennifer Mattei, founder of Project Limulus, reports that the number of pairs of horseshoe crabs coming up to lay eggs on CT beaches is declining and the number of females coming up alone, without a mate is increasing. In Long Island Sound, males are finding it difficult to find females because of their scarcity. Mattei has recommended a moratorium on harvest until both New York and Connecticut can agree on a management plan for the horseshoe crabs of Long Island Sound, including more enforcement against illegal harvesting. To help protect horseshoe crabs and other species that are harvested Mattei also supports the idea of establishing the first Marine Protected Area (MPA) in Long Island Sound, where all the species within the boundary of the MPA would be protected from harvest including horseshoe crabs. MPAs allow for the conservation and recovery of wildlife populations within and adjacent to them.

VOLUNTEER TO HELP MONITOR HORSESHOE CRAB POPULATIONS

Resource managers monitor horseshoe crabs through beach counts and tagging to better understand their patterns of movement and track their abundance. You can help in the monitoring efforts by reporting a tag to the appropriate agency or by becoming a citizen scientist. Go to the Project Limulus website to learn more.

Additional Resources:

- New York Horseshoe Crab Study

- Ecological Research & Development Group

- Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission

- Long Island Sound Study Horseshoe Crab Indicator

Horseshoe Crab Videos

Jonathanʼs Blue World:

For the first time since the 19th century, an alewife was recorded this spring in the Hutchinson River in southern Westchester near the Bronx border. That sighting is helping to validate an effort by environmental groups and state and county agencies to design a fish passage project on the river to return alewives to their historic spawning habitats.

The alewife was seen in March just below the Pelham Lake Dam in Mount Vernon, the first dam on the river, by Gareth Hougham, president of the Hudson Valley Arts and Sciences, one of the partner groups looking to design a fish passage project at the dam.

Fish passage projects such as removing dams or building fishways over or around dams have proved to be a successful means throughout the US for migratory fish to overcome barriers to spawning habitat. Near the Hutchinson River, fishways have increased river miles for migratory fish in the Bronx River to the south and in the Mianus River in Greenwich to the north. In addition, despite pollution from the impacts of urbanization, the Hutchinson River has an abundance of wading birds preying on fish in the river. While these positive signs led to proposing a fish passage project for the Hutchinson River, evidence of a remnant population of alewives attempting to swim upstream of the Pelham Lake Dam still was missing.

Despite the hurdle of a global pandemic, project partners were determined this spring to monitor the Hutchinson River below the Dam to confirm the presence of migratory fish. On March 26, Hougham took two fish traps and placed them in the river below the dam. On March 27, Hougham checked the traps and found (along with some carp) one female alewife. This alewife confirmed that the Pelham Lake Dam does indeed block fish passage and migratory spawning alewife are still present in the river.

In 2018, Hougham’s organization, HVAS, applied for and received a tributary restoration and resilience grant from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation to study the feasibility of fish passage for alewife at the Pelham Lake Dam. In partnership with Westchester County and with guidance from Save the Sound, NYSDEC, Queens College, and the Wildlife Conservation Society, the project is underway, and a contractor to design the fishway is expected to be selected soon.

The Hutchinson River begins in Scarsdale and flows 10 miles south through southern Westchester County and the northeastern Bronx, emptying into Eastchester Bay and western Long Island Sound. The river has suffered from years of human alteration. Today, the impact on the river can still be seen from mouth to headwaters. The river contains Combined Sewer Overflows and is bordered by concrete plants, scrap yards, parkways, an Amtrak line, Co-Op City (the largest housing project in the world), and the Pelham Bay Landfill, which was closed in the 1970s.

One of the major impacts to the health of the river is the existing dams. At the end of the 19th century into the early 1900s the New Rochelle Water Company dammed the river in several locations to create a reservoir system for the surrounding area. Although these reservoirs are now obsolete, the dams still exist creating impassable barriers for fish such as alewife. Alewives spend most of their lives in the ocean and only enter local freshwater tributaries in the spring to spawn. Once they spawn the adults return to the ocean and the juveniles grow up in the river throughout the summer. In the fall, the juveniles head to the ocean and, once mature, return in 3-5 years to spawn in their natal river. They are considered to be an integral part of freshwater and marine food webs, including as food for striped bass, osprey, cod, and trout.

Estuary programs in New York State, including the Long Island Sound Study and the Peconic Estuary Partnership, and the NYSDEC Hudson River Fisheries Unit, are working with partners to prioritize and evaluate the removal or modification of impediments to fish passage. If a successful design at Pelham Lake Dam, which is in Willson’s Woods Park, leads to a fish passage project, it will be the first in Westchester County in the Long Island Sound watershed. The program manager for NYSDEC is Vicky O’Neill, a NEIWPCC environmental analyst who is also the Long Island Sound Study Habitat Restoration and Stewardship coordinator in New York.

A new nationally competitive grants program designed to support projects that address issues threatening the well-being of coastal and estuarine areas is now seeking proposals for grants ranging between $75,000 and $250,000.

The National Estuary Program Coastal Water Watersheds Program is being administered by Restore America’s Estuaries in cooperation with the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Organizations with project proposals within Estuaries of National Significance, including Long Island Sound, are eligible to apply.

The deadline to provide letters of intent, the first step in the two-step application process, is August 7. More information, including a download of the Request for Proposals and a registration link to an informational webinar in June, is available on the Restore America’s Estuaries website.

Established in 1987 through the Clean Water Act, the National Estuary Program is an EPA place-based program dedicated to protecting and restoring the water quality and ecological integrity of 28 estuaries across the country.

The CWWP grant program will fund projects within the geographic areas shown here that support the following Congressionally-set priorities:

- Loss of key habitats resulting in significant impacts on fisheries and water quality such as seagrass, mangroves, tidal and freshwater wetlands, forested wetlands, kelp beds, shellfish beds, and coral reefs;

- Recurring harmful algae blooms;

- Unusual or unexplained marine mammal mortalities;

- Proliferation or invasion of species that limit recreational uses, threaten wastewater systems, or cause other ecosystem damage;

- Flooding and coastal erosion that may be related to sea-level rise, changing precipitation, or salt marsh, seagrass, or wetland degradation or loss;

- Impacts of nutrients and warmer water temperatures on aquatic life and coastal ecosystems, including low dissolved oxygen conditions in estuarine waters; and

- Contaminants of emerging concern found in coastal and estuarine waters such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and microplastics.