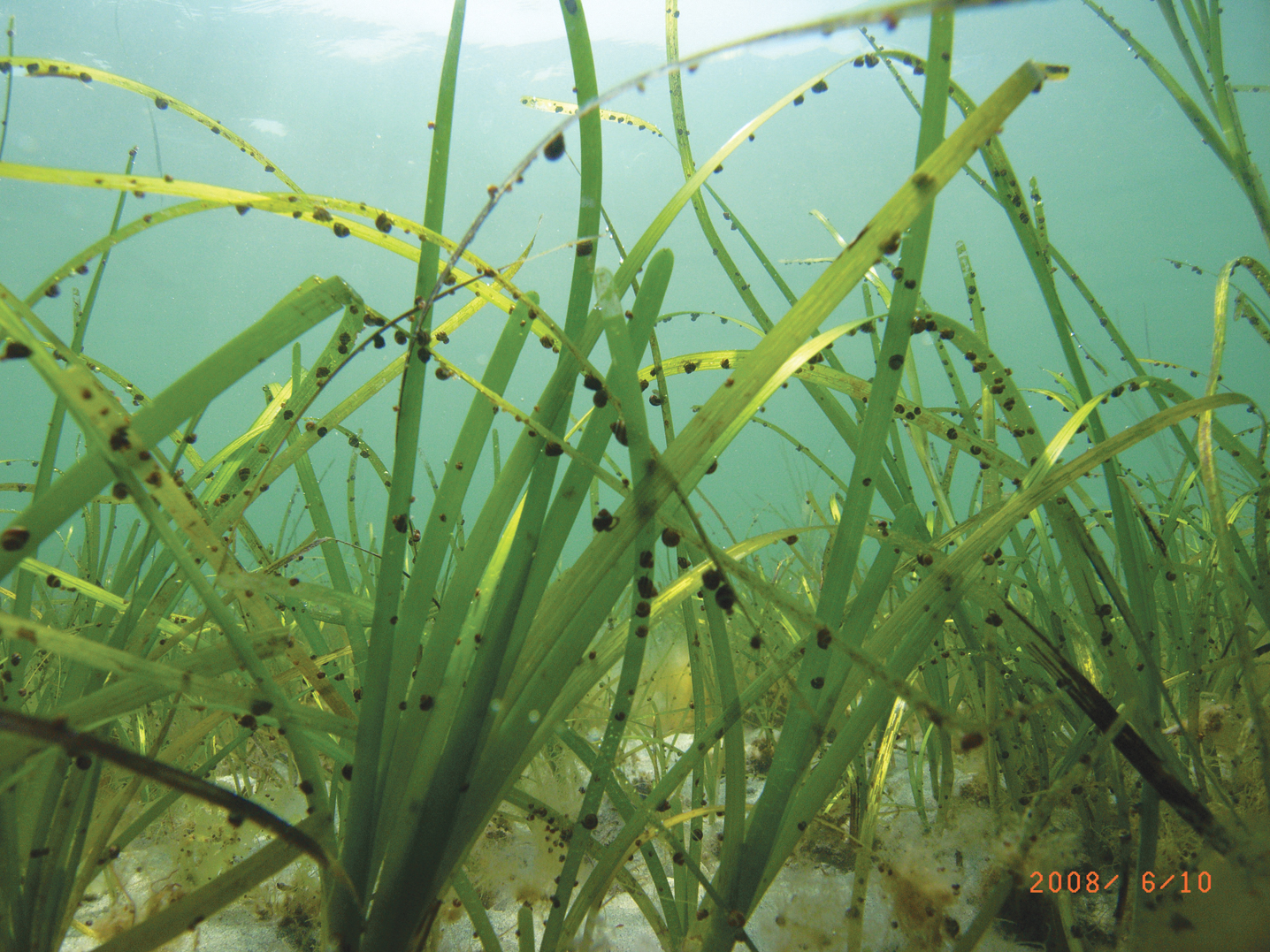

Over a century ago, eelgrass meadows could be found all around coastal Long Island Sound. Today it mainly exists in some of eastern Connecticut’s bays, coves, and harbors and the North Fork of Long Island, Plum Island, and around Fishers Island in New York.

Eelgrass, Zostera marina, is found on sandy bottoms or in estuaries, usually submerged or partially floating during low tide. Most eelgrass are perennial. They have long, bright green, ribbon-like leaves, the width of which are about 0.4 inches. Short stems grow up from extensive, white branching rhizomes. The flowers are enclosed in the sheaths of the leaf bases; the fruits are bladdery and can float.

Why is Eelgrass Important

Eelgrass provides important ecosystem services. Here are examples:

- Serves as important nursery habitat, refuge from predators, and food source for key recreational and commercial fish species.

- Prevents shoreline erosion by stabilizing sediment and reducing the intensity of wave impacts.

- Captures and stores carbon (i.e., carbon sequestration or known as blue carbon [PDF] )

- Removes excess nitrogen from the water column (i.e., denitrification)

Restoring Eelgrass

Eelgrass needs clean water, sunlight, and the right sediment to grow, along with optimum water temperatures. Because of its importance for the health of the Sound and its shoreline, government agencies and environmental organizations are trying to restore eelgrass. But it’s challenging to have all the components in place for successful restoration. The Long Island Sound Study has a strategy to to protect existing eelgrass meadows and create opportunities to increases their extent. Check out the following web links to learn more:

- Long Island Sound Eelgrass Management Strategy (see report in the media center)

- Eelgrass Extent (see Ecosystem Targets and Supporting Indicators microsite)

- Embayment Water Clarity (see Ecosystem Targets and Supporting Indicators microsite)

What You Can Do!

In the meantime, you can help out to protect our eelgrass in Long Island Sound (and other estuaries). Here are some actions you can do:

- Consider not using or reducing fertilizer to lawns as this will decrease nutrients to the Sound.

- Dispose and recycle trash properly to keep marine debris out of the waters.

- Boat responsibly! Slow down or trim up your engine’s prop in shallow areas with eelgrass.

- Volunteer for restoration activities. Check out the Long Island Sound Study Facebook and Instagram account (@lisoundstudy) to keep up with upcoming events.

- Raise awareness and educate your peers!! Spread the word about the importance of seagrass to continue to better protect and restore Long Island Sound.

Dive into Eelgrass with a Story Map!

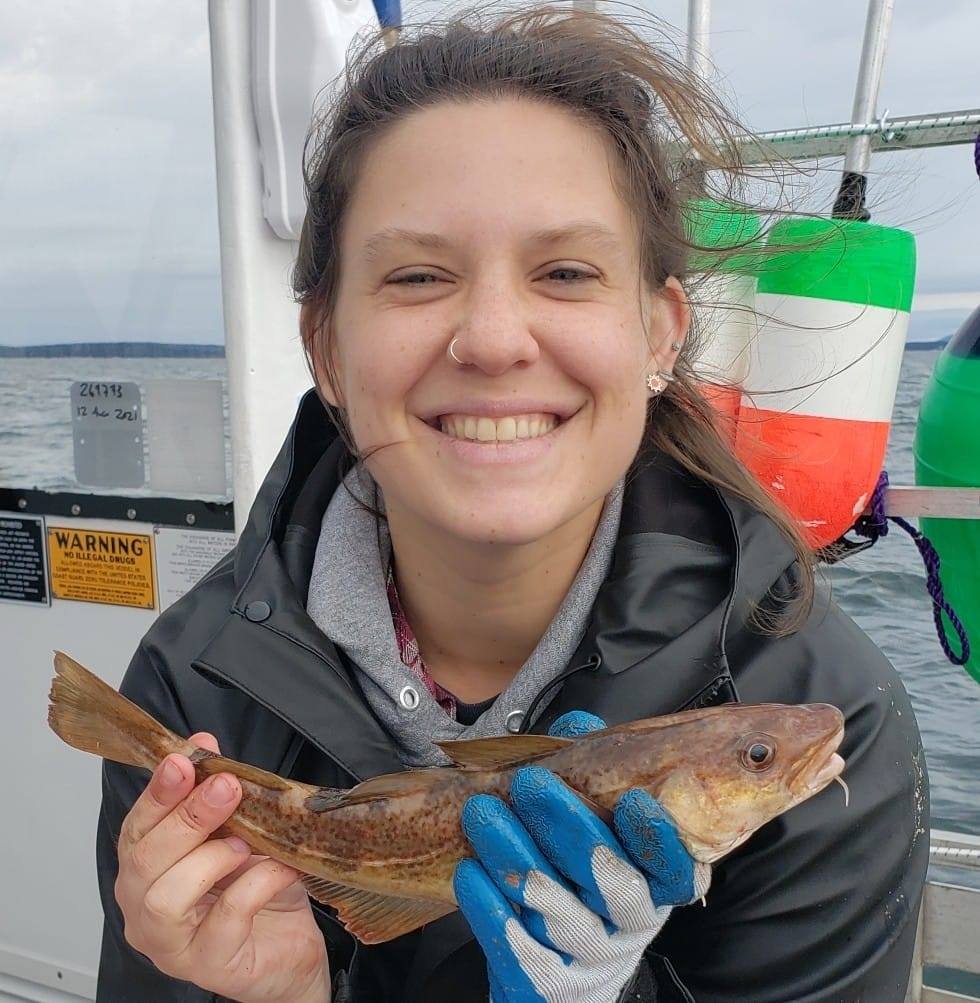

Cayla Sullivan, one of the three divers exploring eelgrass off Fishers Island in this photo, has created a Story Map in ArcGIS that covers a lot of information about the history of eelgrass in the Sound, where it can be found today, and its importance. It’s available on the ArcGIS website.

In September 2023, CT DEEP and partners removed Dana Dam, also known as Strong Dam, from the Norwalk River located in Wilton, CT, opening 10 miles of river for fish passage. The dam’s removal has been a multi-year project which reconnected fourteen miles of free-flowing river to Long Island Sound.

This article was originally published in December 2022 as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law fact series. It was updated on August 22, 2023 and again on February 15, 2024. You can view the original fact sheet here.

With funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) completed the removal of Strong Pond Dam in Wilton, CT, on September 11, 2023, opening an additional 10 miles of river habitat for migratory fish swimming from Long Island Sound.

The Strong Pond Dam, also known as the Dana Dam, was the first barrier migratory fish encounter after swimming upriver on the Norwalk River from Long Island Sound. Planning for its removal began in the 2000s.

In 2020, LISS awarded CT DEEP $2.2 million for the dam’s removal and demolition began in 2021. The final phase of construction, completed in September 2023, focused on removing the dam and restoring the river section. To support the final demolition phase, LISS contributed an additional $250,000 to the project using BIL funds.

Over the next year (2023-2024), efforts will focus on restoring the riverbank, which will include planting 1.5 acres of vegetation to benefit birds, mammals, amphibians, and other wildlife. Save the Sound, a LISS partner, will document regrowth and monitor the passage of migratory and resident fish populations up the Norwalk River. The former site of Dana Dam is expected to return to its natural state over time.

Funding was administered through CT DEEP, and the project was led by LISS partner Save the Sound, with collaboration from Trout Unlimited, the Norwalk River Watershed Initiative, and the Town of Wilton.

Improving access for migratory fish in the Norwalk River is an important step to restoring the health of the river and Long Island Sound. Important species like herring and sea lamprey previously had no access to these historic spawning grounds since construction of the dam.

With its removal, these species can reach the spawning grounds and improve the ecological balance in the river and Sound. Flooding around the dam had also threatened parts of Downtown Wilton and the nearby railroad infrastructure. These risks have been reduced with the dam’s removal.

Since 1998, the Long Island Sound Study and its partners have successfully reopened nearly 433 miles of rivers and streams for fish passage in Connecticut and New York.

Modeling and mapping research project tracks and predicts climate change’s influence on cold and warm water-adapted species in Long Island Sound

By Juanita Asapokhai

Tides of Change

Like an aquatic hotel, at any point in the year, Long Island Sound plays host to a diverse array of species, including over 170 different species of fish and invertebrates. Changes in the species, location, and distribution of fish residing within the Sound shift with the seasons and temperatures. In fact, many fish in the Sound have evolved to survive in specific temperature ranges, and migrate to other habitats when the seasons cycle. Cold-adapted fish, like winter flounder, skates, and hake, which dwell and feed at the bottom of water bodies, swim away from the Sound and toward colder waters when the summer and fall months hit. On the other hand, warm-adapted fish, among them black sea bass and summer flounder, continue to thrive as the temperatures rise. As global warming drives temperatures in the Sound upwards, the ability of warm-adapted fish to continue living in Long Island Sound when the tides turn towards warmer weather gives them a critical advantage over their cold-adapted counterparts. Learning about how the Sound has changed over time and the impact these changes have on the distribution and survival of cold-adapted fish is a crucial step in developing management strategies to support and protect these creatures in their changing habitat.

As part of the research to inform these strategies several students, including Robyn Linner, a PhD candidate at Stony Brook University, is working with Dr. Yong Chen, Professor of Marine Sciences, and a bi-state team of marine scientists and resource managers in developing habitat suitability indices (HSIs), which will analyze a variety of environmental factors to determine ideal habitat conditions for various cold- and warm-adapted species in the Sound. The team has already completed an initial literature review for the project, assembling research about the environmental needs and temperature thresholds for several cold and warm water-adapted species of Long Island Sound over time. The team is using long-term datasets collected by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation to identify environmental-related changes to cold- and warm-adapted fish distribution that have occurred over time and map the area and structure of the fishes’ Sound habitat. The goal is that this data will provide valuable information that reinforces or potentially redirects current Sound ecology monitoring programs and species conservation efforts.

Assessing the Sound: The Habitat Suitability Index

The relationship between a species and its habitat is essential to its survival. A fish’s habitat is characterized by many variables, from salinity to sediment type, to temperature and levels of dissolved oxygen, to food-chain dynamics between predators and prey. Changes to these conditions make or break a species’ ability to remain and thrive in a habitat.

A habitat suitability index (HSI) will factor in all of these variables over a specific period of time to calculate a number that represents the appropriateness of the habitat, on a scale of 0 (least suitable) to 1 (optimal). The HSIs can then be used to identify key areas within the Sound that are best suited to the environmental needs of different cold- or warm-water-adapted species.

“We run the analysis and try to understand what the ideal ranges are for each variable such as salinity, sediment, etc.,” Linner explained. “And then we create maps that have information about the [conditions] in that location.”

The HSIs can be used to identify key areas within the Sound that are best suited to the environmental needs of different cold- or warm-water-adapted species. “Since we’re looking at habitat through time, we can see how their distribution has changed, but also how we might expect them to change in the future under different climate scenarios,” Linner said. “So, it’s a really good visual way to identify some of these habitats and predicted changes.”

Alongside Chen, Linner, who has worked in Chen’s fisheries ecology lab for five years, and the research team are studying eight cold-adapted fish, and seven warm-adapted fish species found in the Sound. The cold-adapted species include windowpane flounder, little skate, fourspot flounder, winter flounder, spotted hake, silver hake, and red hake. The warm-adapted fish species selected included scup, butterfish, summer flounder, black sea bass, striped sea robin, and northern sea robin. The team is also studying the biology and environmental needs of two crustacean species, the cold-adapted American lobster and warm-adapted blue crab. The fish and crustacean species examined in the study were selected by the team because of their strong temperature preferences, and the significant implications that climate change and changing temperatures have on the abundance and health of the species.

Many cold-adapted fishes migrate towards colder water offshore or to the north, including the Gulf of Maine, when temperatures rise in the summer and stay warm in the fall. But for the fish that don’t and remain in the Sound and are forced to tolerate the suboptimal warmer temperatures, they may face reduced movement activity, feeding, and decline in weight, which may have negative effects on the reproduction and egg count of cold-adapted fish species.

On the other hand, warm-adapted species have the opportunity to expand their range in Long Island Sound as they continue to fare in the warmer temperatures. Species like the butterfish, black sea bass, and blue crab are experiencing increases in abundance that were not previously observed in the Sound due to their ability to spread out into formerly uninhabited waters in the Sound. Their expansion has several consequences. The Sound acts as a supportive nursery for several species to spawn their young and for juvenile species to develop before maturation, safe from access by predators. Voracious predator species like black sea bass and others consume young fish and may threaten the nursery function of the Sound, Linner said.

Cold-adapted fish displaced from the Sound may run into difficulty finding a habitat that has the unique conditions present in Sound. Further, as warmer temperatures enable warm-adapted fish to remain in the Sound for longer periods of time and extend their range, cold-adapted species, like the winter flounder, find themselves in greater competition with warm-adapted species . “Moving into these new areas that allow them [warm-adapted fish] to thrive can have really unpredictable consequences,” said Linner. “We aren’t used to seeing this combination of species in the past.” The impact that changing fish distribution has had on fishery economies and the livelihood of commercial fishers is also significant, demonstrated dramatically in the case of the American lobster, whose major decline toppled over a booming lobstering industry.

Mapping the Sound

Linner and the research team are close to completing the analysis and development of maps that show changes in fish distribution over time, using spatial indicators like center of gravity and evenness to track the species’ movements. “Center of gravity” indicates where in the water a species tends to congregate, and can help identify changes in the east-west and north-south distribution of a population within the Sound. “Evenness” refers to how clustered or aggregated a species is, which reflects whether a species is clumping together or spreading out. Whether or not a species is aggregating can affect the catchability of a species, and can make estimating their abundance difficult.

“These (spatio-temporal maps) help to get just a quick visual snapshot of some of these changes through time, before we even run the habitat suitability models, to get a sense of which species have experienced the most change,” Linner said.

Much of the information about abundance over time used in this study was collected through the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection’s (CT DEEP) Trawl Survey. While aboard a research vessel, researchers survey the entire Long Island Sound in the fall and spring, recording data about fish length, weight, and abundance for various species. Linner and the research team are working with data collected through the CT Deep Trawl Survey between 1984, when the program started, and 2021.

The HSI maps will support another objective of the research project: creating hindcasting and forecasting models to form a complete picture of the changes that cold- and warm-adapted fish in the Long Island Sound have experienced over time, and what changes can be expected to happen in the future in a variety of different climate scenarios (e.g. changes in salinity conditions, temperature conditions, etc.). The forecasted climate scenarios combine information about climate changes that have already occurred with modeled estimates about the rates of change in the future. By looking at different climate scenarios, Linner said, “You can evaluate different levels of severity. So, if we end up making some changes (to our carbon footprint), we can look at how that might impact these species, instead of only the worst-case scenario.”

Protecting the Sound’s Biodiversity in a Changing Climate

The results of the research team’s work will provide valuable guidance for ecosystem management and monitoring programs in the Sound. It can help identify critical species that may be most negatively or positively impacted by predicted changes in climate, and call attention to key areas where cold-adapted species can go to find thermal refuge. Linner hopes that the research can be used to inform necessary spatial planning policy, or direct monitoring towards sentinel species that will signal if more urgent climate-related changes are taking place within the Sound.

Interventions like these “might help mitigate how quickly some of these changes occur, which may allow some of these species to grow their populations to a point that allows them to be a little more resilient,” Linner said.

“It’s really about trying to highlight specific species, specific areas, and specific issues that we think that we might be able to make some changes to, to help these species deal with the changing temperatures.”

Juanita Asapokhai was a Communications Intern for the Long Island Sound Study in summer 2023. She attends Tufts University and will be graduating with degrees in Community Health and Sociology in the spring of 2024.

By Juanita Asapokhai

Something Is in the Water

At the turn of the 21st century, resource managers were extremely concerned by the quality of the water flowing into Long Island Sound. For decades, the Sound had been absorbing a high influx of nitrogen from human sources—including through water discharges from wastewater treatment plants, fertilizer runoff, and stormwater runoff—and facing head-on the adverse effects of eutrophication, or pollution of a water body by the buildup of certain nutrients. These effects included hypoxia, or low levels of dissolved oxygen, and the overgrowth of algal blooms, both harmful to fish and the overall health of the Sound’s ecosystem. In 2001, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through the Long Island Sound Study, partnered with the states of Connecticut and New York in developing a strategic plan to reduce the nitrogen pollution load in the Sound with the implementation of the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL). Since the institution of the TMDL, which includes billions of dollars in investments in upgrading wastewater treatment plants to reduce water discharges containing nitrogen, the Sound has seen significant improvements in its water quality metrics, including a decline in the area and volume of the Sound experiencing hypoxia. What these programs have not captured, however, are the impacts that the TMDL water quality management regulation has had on the marine life of the Sound over time.

This gap is exactly where the research of paleoecologist Dr. Gregory Dietl of the Paleontological Research Institution fits in. Paleoecologists are scientists who study organisms and their environments across different geological timescales. With a $39,000 grant from the Long Island Sound Study’s research grant program, Dietl and his team will be conducting an analysis across recent timescales of the assemblages of dead mollusks left behind on the seafloor, comparing biological indicators of habitat condition using mollusks that lived pre-TMDL and mollusks that lived post-TMDL. The mollusks are a proxy for all invertebrates on the seafloor to: 1) assess how improved water quality in the Sound has affected benthic macroinvertebrate communities, and 2) how much farther nitrogen reduction efforts should go to promote their health and survival.

“The TMDL was developed to try and reduce the amount of nitrogen coming into the Sound, which would hopefully then reduce the extent of hypoxia. From that perspective, the management intervention seems to be working,” said Dietl, whose Ithaca-based organization is affiliated with Cornell University. “What we don’t know is if macroinvertebrate communities responded to the improved water quality in the Sound over the same time period.”

Comparing the past with the present, said Dietl, should help determine if areas of the Sound where water quality has improved has led to “habitat conditions that could support diverse macroinvertebrate communities” or places that are only fit for organisms that “are tolerant of stress.”

Using Snails, Clams, and other Mollusks to Study Biological Health of the Sound.

To assess the impact of water quality improvements on aquatic life, accomplished through the TMDL, Dietl will be studying benthic macroinvertebrates, small animals without a backbone that live on the seafloor (the “benthos”). They include mollusks, which are soft-bodied animals with shells, such as mussels, clams, and snails. Macroinvertebrates are useful to study as indicators, according to EPA’s National Coastal Condition Assessment website, because they are easy to collect and easy to identify in the laboratory, they are around because they have limited mobility, they respond to human disturbance in predictable ways, and they differ in their tolerance to pollution.

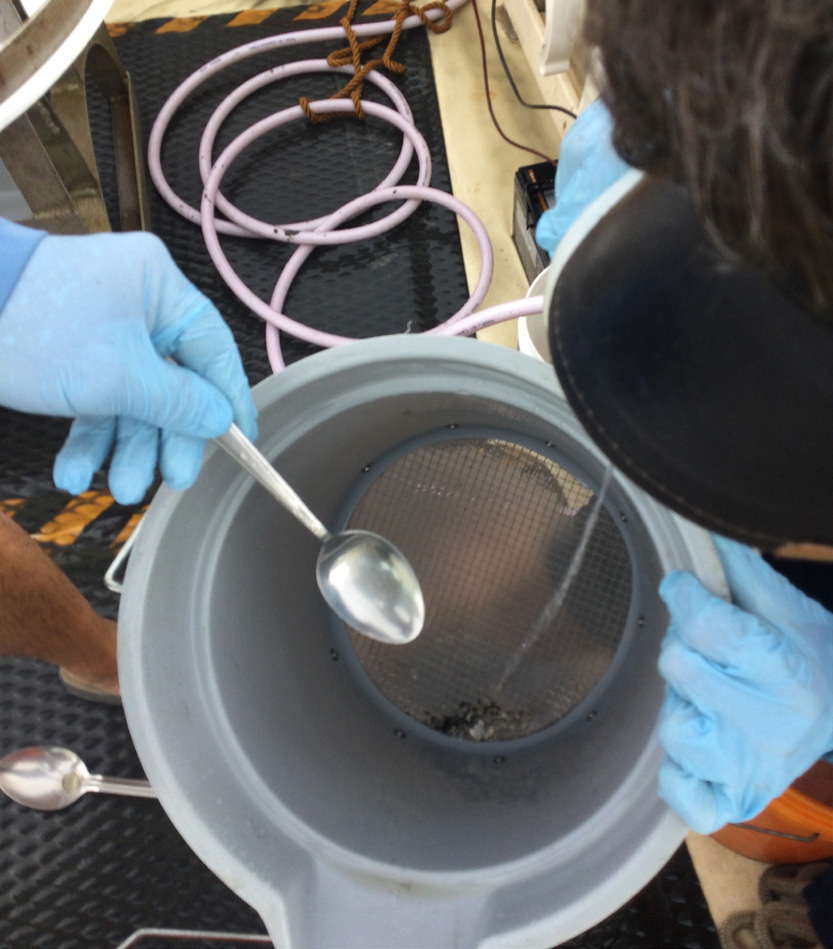

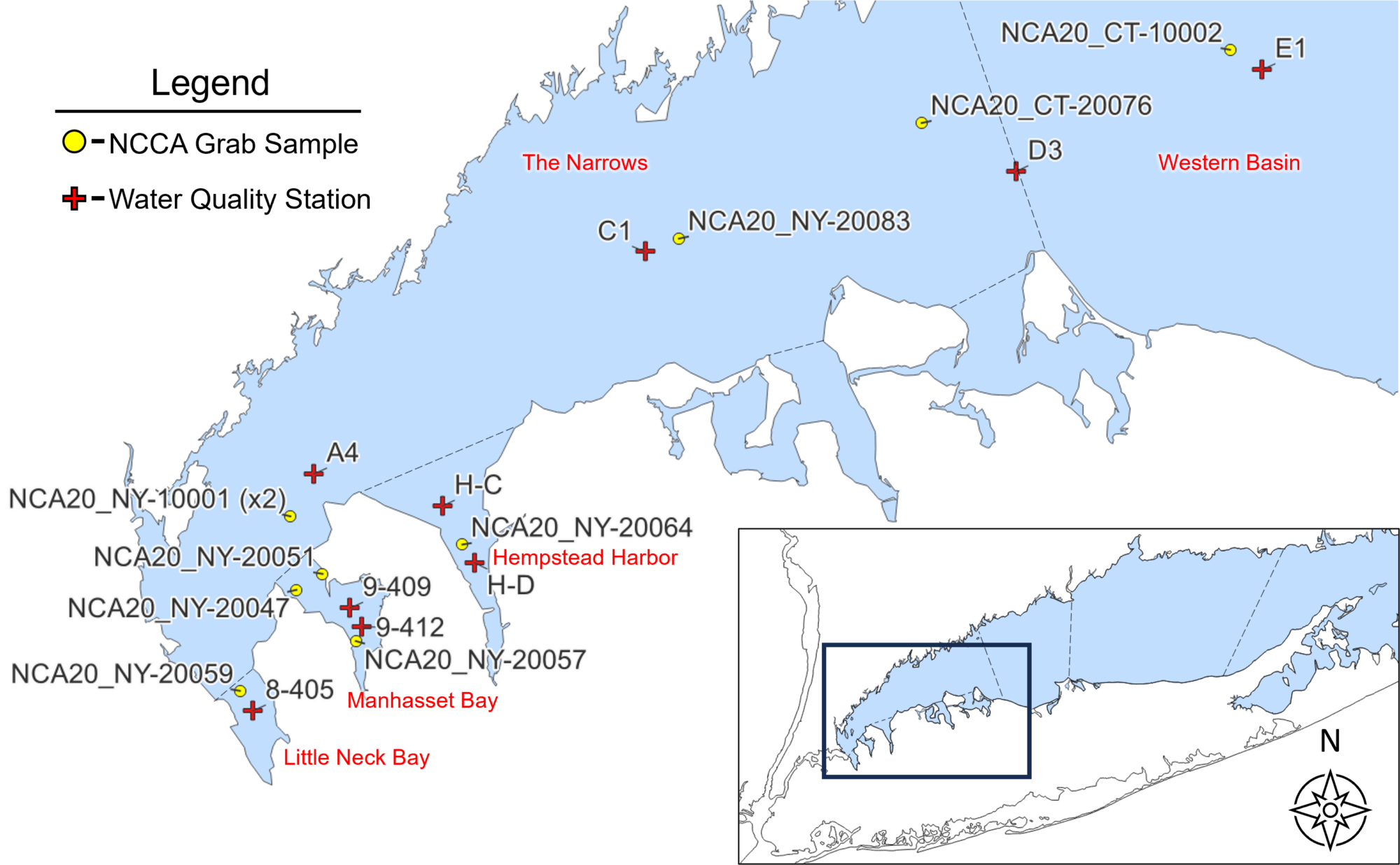

The NCCA collects mollusks about every five years as part of a water quality monitoring program that tracks the nation’s coastal waters, and the Great Lakes. The sampling includes Long Island Sound, a resource which Dietl is able to use for his research. In 2020 and 2021, sampling was conducted by EPA contractors and the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection at 140 stations across the Sound. These are areas near where CT DEEP and the Interstate Environmental Commission also conduct water quality monitoring for the Long Island Sound Study. The bottom-dwelling macroinvertebrates were collected from a boat using a clam-like shovel device called a Van Veen sediment grab. The live specimens were then separated from the sediment with a sieve and preserved and placed in jars to be sent to a lab for identification.

From the 2020-2021 data, Dietl will be creating a record of the post-TMDL period of the project with an M-AMBI score, a biological index based on three metrics – species richness (the number of species), species diversity (which includes not only the number of species but the relative abundance of each species in the community), and AZTI’s Marine Biotic Index (AMBI), which measures how well the different species in a community tolerate environmental stressors such as eutrophication and hypoxia. Good sites have a wide variety of species, more diversity, and an increase in species that are intolerant of pollution because more of these species can thrive when water quality is good. M-AMBI scores range from zero to one, with scores <0.39 indicating poor condition.

“If you think of it this way,” said Dietl. “Each of the species that we identify can be classified by how sensitive it is to pollution in the environment. Some species are sensitive to pollution and other ones are going to be tolerant of it.”

Dietl’s project focuses on 10 sampling stations in the western Sound and Narrows. These are locations that are close to New York City and its densely populated suburbs, areas that have historically experienced the most pollution in the Sound. Many of these sites, however, also have experienced reductions in hypoxia since the TMDL was adopted and nitrogen has been reduced through wastewater treatment upgrades. Of the 10 sites Dietl selected, nine have seen moderate to high water quality improvements from 1994-2021, while the tenth has seen a moderate decline in water quality according to the Long Island Sound Water Quality Monitoring Program, the monitoring program conducted by CT DEEP and IEC.

Going Back In Time: A Paleoecological Approach to Tracking Water Quality

Using the NCCA standards enables Dietl to build efficiency for the project. For example, he does not have to collect, identify, and assess mollusks from the post TMDL era because the data already exists. As it turns out the NCCA monitoring program also provides an important head start for paleoecologists such as Dietl to conduct the pre- TMDL assessment as well. The monitoring crews that collect live specimens with the sediment grab tool also are picking up shells from the surface of the seafloor and just below the surface. These shells are the remains of mollusks whose soft bodies decomposed at an undetermined time. Like the live specimens, the shell remains also are collected and stored in jars. But normally they would get discarded without being identified, said Dietl. For this project, however, Dietl received permission from EPA to study the shell remains so he could get a historical record of the 10 sites and conduct the comparison study. To do that, Dietl and his research team first needed to determine the age of the shells, which are referred to as death assemblages when sorted out and identified, to see if they corresponded to the period before the TMDL and when CT DEEP was collecting water quality monitoring data. He sent a sub-sample of 200 shells to partners at the Arizona Climate and Ecosystems (ACE) Isotope Laboratory at the Northern Arizona University to conduct radio-carbon dating to estimate the ages, and the results were what he was looking for.

“They’re mostly coming back from the 1980s and 1990s,” said Dietl. “So, we have a good pre-TMDL baseline to compare our dead shells to the data from the living community.”

Dietl and his team are now going through the process of identifying and counting thousands of the shells from the 10 sites, classifying each species found by its tolerance to pollution, and estimating each sample’s M-AMBI score. He hypothesizes that biological condition as reflected by the change in M-AMBI scores from the pre-TMDL and post TMDL periods will correlate with improvement or decline in water quality from the 1990s to the 2020s.

“At sites where water quality has improved, we predict that ecological quality (estimated by our M-AMBI analyses using mollusks) will increase since the TMDL intervention,” said Dietl. “We expect a less-pronounced response at sites where water quality has not improved as much and even a decline at one site where water quality has decreased since the TMDL intervention.”

The Connection Between Paleoecology and Modern-Day Management of the Sound

This retrospective look and approach to create a historical record of biological changes to mollusks in the Long Island Sound comes from the field of conservation paleobiology, or the application of paleoecological insights and data derived from fossils, sediment cores, and other natural archives to modern-day ecosystem management and conservation work. As the Curator of Cenozoic Invertebrates at the Paleontological Research Institution Dietl’s work focuses on this emerging research area. Paleoecologists use death assemblages to study a variety of ecological changes.

“Reconstructing the past…gives us some sense of what’s possible, or how much something has changed,” Dietl said. “There’s a lot of value in establishing a narrative of how a place has changed over time and how humans have impacted the environment.”

As he and his research team work through analyses of mollusk shells using the M-AMBI metric, Dietl emphasizes the importance of paleoecology in the long-term management and conservation effects for the Sound. “There has been very little monitoring of the benthic macroinvertebrate communities in response to the TMDL intervention, because the resources weren’t available,” he said. “It’s hard to monitor everything, everywhere, all the time.”

The analysis of the dead “residue” of shells from benthic grab samples presents an untapped opportunity for the management community, to see into the past and fill a critical gap in knowing how macroinvertebrate communities responded to the TMDL intervention.

“While managers would have to maintain a monitoring program for years or decades to build a long-term dataset, conservation paleobiologists may be able to address this need retroactively by putting the dead to work,” said Dietl.

For more information about the Long Island Sound Study’s Nitrogen Reduction Strategy, a segment of our Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan, click here.

Juanita Asapokhai was a Communications Intern for the Long Island Sound Study in summer 2023. She attends Tufts University and will be graduating with degrees in Community Health and Sociology in the spring of 2024.

RFP Expected in March; Plan Now to Take Advantage of Workshops, 1-on-1 Sessions, and Grant Writing Opportunities

A total of $12 million in funding for environmental grants is expected to be awarded in the 2024 Long Island Sound Futures Fund grant program. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, which administers the Futures Fund, will be announcing the request for proposals in March. Meanwhile, NFWF has just announced workshops for each of the Long Island Sound watershed’s five states to learn about how to apply for a grant through the RFP process. There are also opportunities to schedule one-on-one consultations and to apply for grant writing assistance.

2024 Futures Fund Grant Program Details

Grants for the 2024 Long Island Sound Futures Fund grant program will be available in five states in the Long Island Sound watershed (New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire). The awards will range from $50,000 to $1.5 million, with a potential of more than $12 million in grants to be distributed. The availability of federal funds estimated in this solicitation will be contingent upon the federal appropriations process. Funding decisions will be made based on level of funding and timing of when it is received by NFWF.

The different funding categories will be based on geography:

- Habitat restoration planning or implementation grants will be available for projects in the Long Island Sound Study coastal zone of Connecticut and New York.

- Resilience, education, water quality, and fish passage grants will be available for projects in the Long Island Sound Study boundary in Connecticut and New York.

- Nutrient/Nitrogen prevention planning or implementation grants will be available for projects in the Long Island Sound boundary in New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

Get Started Now! Share a Project Idea, Register for a Webinar, and Get Grant Writing Assistance

Proposal Labs. One-on-one sessions to receive feedback and guidance about individual proposal ideas. February 2024 through April 2024 (Register)

Applicant Webinar. Group sessions and opportunities for shared learning about preparing a competitive LISFF proposal. For Connecticut and New York applicants, register for March 11 workshop at 1 pm. For Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont applicants, register for March 13 workshop at 1 pm.

One-on-one help to develop project ideas in non-coastal Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Contact Throwe Environmental and learn more about LISFF applicant assistance in the Northeast.

One-on-one help to develop project ideas in coastal Connecticut and New York. Contact a Sustainable and Resilient Communities Extension Professionals (SRC contact map).

Need help writing a grant application in Connecticut and New York? Apply to the Long Island Sound Resilience Grant Writing Assistance Program. The program is administered by the Sustainable and Resilient Communities Extension Professionals.

Contact Victoria Moreno to be put on a mailing list to receive notifications about grants.

Further information about the Futures Fund grant program is available on the Long Island Sound Study website.

The Connecticut and New York Sea Grant Programs announced on January 29 a request for preliminary proposals for the Long Island Sound Study Research Grant Program. Researchers have a deadline of April 8, 2024 to submit preliminary proposals. The grants are expected to be awarded in October for projects that are expected to take place from 2025 to 2026. Visit the CT Sea Grant website for more information about the 2024 grant cycle. Visit the Long Island Sound Study Research Grant Program web page for descriptions of each research project funded since the program began in 2000.

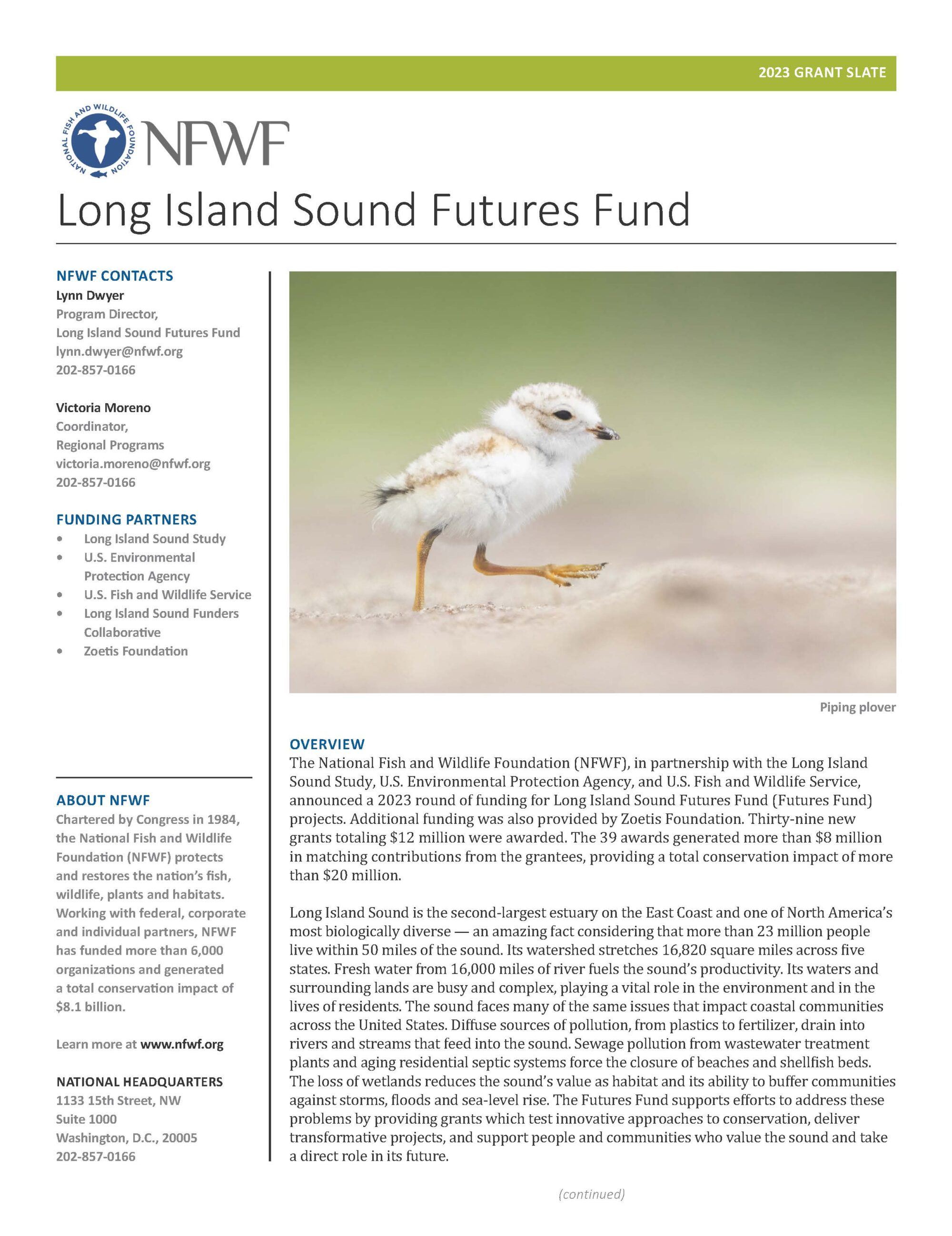

On Dec. 4, 2023, The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), in partnership with the Long Island Sound Study, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, announced a 2023 round of funding for the Long Island Sound Futures Fund projects. Additional funding was also provided by Zoetis Foundation. Thirty-nine new grants totaling $12 million were awarded. The 39 awards generated more than $8 million in matching contributions from the grantees, providing a total conservation impact of more than $20 million.

A fact sheet of each of the projects, originally published on the NFWF website, is available as a PDF in the LISS media center.

GROTON, CT (January 16, 2024) – Elementary, middle and high school students, teachers and the communities of 10 public schools in urban and suburban areas will comprise the new Long Island Sound Schools network, committing to the protection of local watersheds, the Sound and our one global ocean.

With funding by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Long Island Sound Study and facilitated by Connecticut Sea Grant and Mercy University, the program supports schools that implement a school or community-based project and create a plan to increase ocean literacy by engaging students, families and the public.

All the schools are located within the Long Island Sound watershed, from inland areas with waterways that flow into the estuary to shoreline communities. Program funding will provide stipends for lead teachers at each school and up to $5,000 per school to implement projects. The schools will also have access to a network of educators, connections with scientists, community organizations and stewardship sites, and possible travel funds for conference presentations.

“We have all been inspired by a teacher who has opened our minds to new possibilities and ambitions,” said Mark A. Tedesco, director of the EPA’s Long Island Sound Office. “The new Long Island Sound Schools network will support schools, teachers, and students in learning about Long Island Sound and actively engaging in its protection and conservation.”

The project began with a kick-off meeting of member schools on January 4. The schools will be implementing their projects starting on January 15 and concluding on August 15, as well as planning a student symposium and teacher retreat.

“The Long Island Sound Schools network builds on more than 20 years of success with the Long Island Sound Mentor Teacher program,” said Diana Payne, CT Sea Grant education coordinator. “It’s the next logical step—from fostering educators to incorporate Long Island Sound into their curriculum at the classroom level and expanding it to the school and community level.”

The program is modeled on the National Atmospheric and Oceanographic Administration’s (NOAA) Ocean Guardian Schools and the international Blue Schools network.

“This project is a wonderful opportunity for school communities to strengthen their connection to Long Island Sound and our global ocean, inspiring the next generation of ocean stewards,” said Meghan Marrero, professor of secondary science education and co-director of the Mercy University Center for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) Education. Payne and Marrero are co-leaders of the project.

The network schools in Connecticut are: Flanders Elementary, East Lyme; Mystic River Magnet; Torrington High; Trumbull High; Walter Fitzgerald Campus, Southport; and Waterford High. The network schools in New York are: Jefferson Elementary, New Rochelle; PS175X, Bronx; Smithtown High School West; and Trinity Elementary, New Rochelle.

For information about the program, contact Diana Payne at: diana.payne@uconn.edu.

This news release was originally published on the Connecticut Sea Grant website on January 16, 2024

On January 27, don your hat and gloves and join us for a morning of bird-watching! Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center and Connecticut Sea Grant will lead a guided hike around the Barn Island Wildlife Management Area in Stonington to look for winter waterfowl (namely ducks!).

Barn Island is one of the Long Island Sound Study’s Stewardship Atlas sites, an area with significant ecological and cultural value. At 1,024 acres, Barn Island is the largest and single most ecologically diverse coastal Wildlife Management Area in Connecticut.

Barn Island Waterfowl Walk

Date: Saturday, January 27

Time: 9:30 a.m.-10:30 a.m.

Location: Boat Ramp, at the end of Palmer Neck Road in Stonington, CT

Register: Free registration at Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center website

For more information contact Maggie Cozens, Long Island Sound Study Outreach Coordinator, 860-501-2223, or email her at: margaret.cozens@uconn.edu.

Contact:

Kristen Peterson, for National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), 410-353-3582, kpeterson@thehatchergroup.com

Mikayla Rumph, U.S. EPA Region 1 (New England), 617-918-1016, rumph.mikayla@epa.gov

Stephen McBay U.S. EPA Region 2, 212-637-3672, mcbay.stephen@epa.gov

CONNECTICUT (December 4, 2023) – Today, federal and state environmental agencies and officials from New England and New York, including the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), announced 39 grants totaling $12 million to organizations and local governments to improve the health of Long Island Sound. The grants are matched by $8 million from the grantees themselves, resulting in $20 million in total conservation impact for projects in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont.

In all, these Long Island Sound Futures Fund (Futures Fund) 2023 grants will support projects that improve water quality by preventing 2.7 million gallons of stormwater and 101,000 pounds of nitrogen pollution from flowing into Long Island Sound waters. The projects will also remove 120 tons of marine debris from the sound and support planning for restoration of 880 acres of coastal habitat and 102 miles of river corridor vital to fish and wildlife. And, the projects will reach 30,000 people through environmental education programs that increase awareness of how to improve the health and vitality of the Sound. Funding for the grant program comes from the EPA as part of the Long Island Sound Study (LISS), with additional support from FWS, NFWF and The Zoetis Foundation.

“Everyone that lives, works, and plays on the Sound deserves clean water and equitable access. By Investing in America, these grants, along with the huge investment in the Sound from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, put us on the right path,” said EPA New England Regional Administrator David W. Cash. “Because of these investments, EPA is making good on its promises to uplift communities, make them more resilient to climate change, and improve the health of the Sound as a whole.”

“EPA’s continued investments in locally based programs in and around Long Island Sound will tackle water quality improvements, reduce nitrogen pollution and restore coastal habitat,” said Regional Administrator Lisa F. Garcia of EPA Region 2. “EPA is proud to support these innovative and impactful projects that will improve the health and resilience of this vital estuary for generations to come and ensure that all communities have a voice and a role in the protection and restoration of the Sound.”

The LISS initiated the Futures Fund in 2005 through EPA’s Long Island Sound Office and NFWF. The grant program has a strong history of making environmental improvements by supporting people and communities who value the sound and take a direct role in its future. Since its inception, the Futures Fund has invested $56 million in 640 projects. The program has generated an additional $65 million in grantee matching funds towards these projects for a total conservation impact of $121 million. The projects have opened 121 river miles for fish passage, restored 842 acres of fish and wildlife habitat, treated 208 million gallons of stormwater pollution, and engaged 5 million people in protection and restoration of the Sound.

“This year’s grants provide support for grantees and their partners to implement projects that benefit community residents, farmers, fish, and wildlife” said Jeff Trandahl, executive director and CEO of NFWF. “The Long Island Sound’s watershed covers more than 16,000 square miles in six states and the funding today represents a commitment to foster the progress made over many decades towards a healthier, cleaner and more resilient watershed that will benefit wildlife and people for generations to come.”

“The projects funded today conserve and restore vital habitat for threatened and endangered wildlife like piping plovers and roseate terns, as well as include working directly with communities to create a future landscape more resilient to climate change,” said Wendi Weber, Northeast Regional Director for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Removing dams and replacing culverts clears the way for migratory fish while reducing the risk of flooding. Living shorelines support fish and shellfish while buffering destructive storm surge. These grants support a brighter future for the people and wildlife of Long Island Sound.”

“Since 2005, the State of Connecticut has been privileged to benefit from the groundbreaking and critical work of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation through its Long Island Sound Futures Fund. Projects supported by the Futures Fund lead to real world advancement and improvements to the Long Island Sound, our most cherished natural resource,” said Emma Cimino, Connecticut Deputy Commissioner of Energy and Environmental Protection. “Today Connecticut joins in celebrating the award of over $7.5 million in 23 grants to 22 recipients in Connecticut, which leverage almost $4 million in additional local funding. These important and forward-thinking projects range from reducing nitrogen pollution and removing barriers to fish passage to improving the resilience of our coastal communities and providing pathways to conservation careers to young people from environmental justice communities. We are grateful to our federal partners for this impactful funding in Connecticut and those awarded in New York.”

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) Commissioner Basil Seggos said, “The Long Island Sound is an irreplaceable natural resource to New Yorkers and neighbors alike. Working hand-in-hand with stakeholders and key partners like the Long Island Sound Futures Fund, DEC is proud to see the extensive investments and efforts underway to restore and protect the Sound for future generations by improving water quality, conserving critical habitats, responsibly increasing recreational access, and empowering the public to safeguard this cherished natural resource. DEC congratulates and thanks grant awardees for their sustained dedication to the conservation of this vital ecosystem.”

A complete list of the 2023 Long Island Sound Futures Fund grants recipients is available here. See a list of quotes from elected officials and partners about today’s grant announcement here. To learn more, please visit the NFWF Long Island Sound Futures Fund website.

Long Island Sound is an estuary that provides economic and recreational benefits to millions of people while also providing habitat for more than 1,200 invertebrates, 170 species of fish and dozens of species of migratory birds. The grant projects contribute to a healthier Long Island Sound for everyone, from nearby area residents to those at the furthest reaches of the sound. All nine million people who live, work, and play in the watershed impacting the sound can benefit from and help build on the progress that has already been made.

About the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

Chartered by Congress in 1984, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) protects and restores the nation’s fish, wildlife, plants and habitats. Working with federal, corporate, foundation and individual partners, NFWF has funded more than 6,000 organizations and generated a total conservation impact of $8.1 billion. NFWF is an equal opportunity provider. Learn more at nfwf.org.

About the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Grants

Every year, EPA awards more than $4 billion in funding for grants and other assistance agreements. From small non-profit organizations to large state governments, EPA works to help many visionary organizations achieve their environmental goals. With countless success stories over the years, EPA grants remain a chief tool to protect human health and the environment. Follow EPA Region 1 (New England) on X and visit our Facebook page. For more information about EPA Region 1, visit the website.

About the Long Island Sound Study

The Long Island Sound Study, developed under the EPA’s National Estuary Program, is a cooperative effort between the EPA and the states of Connecticut and New York to protect and restore the Sound and its ecosystem. To learn more about the Long Island Sound Study, visit the website.