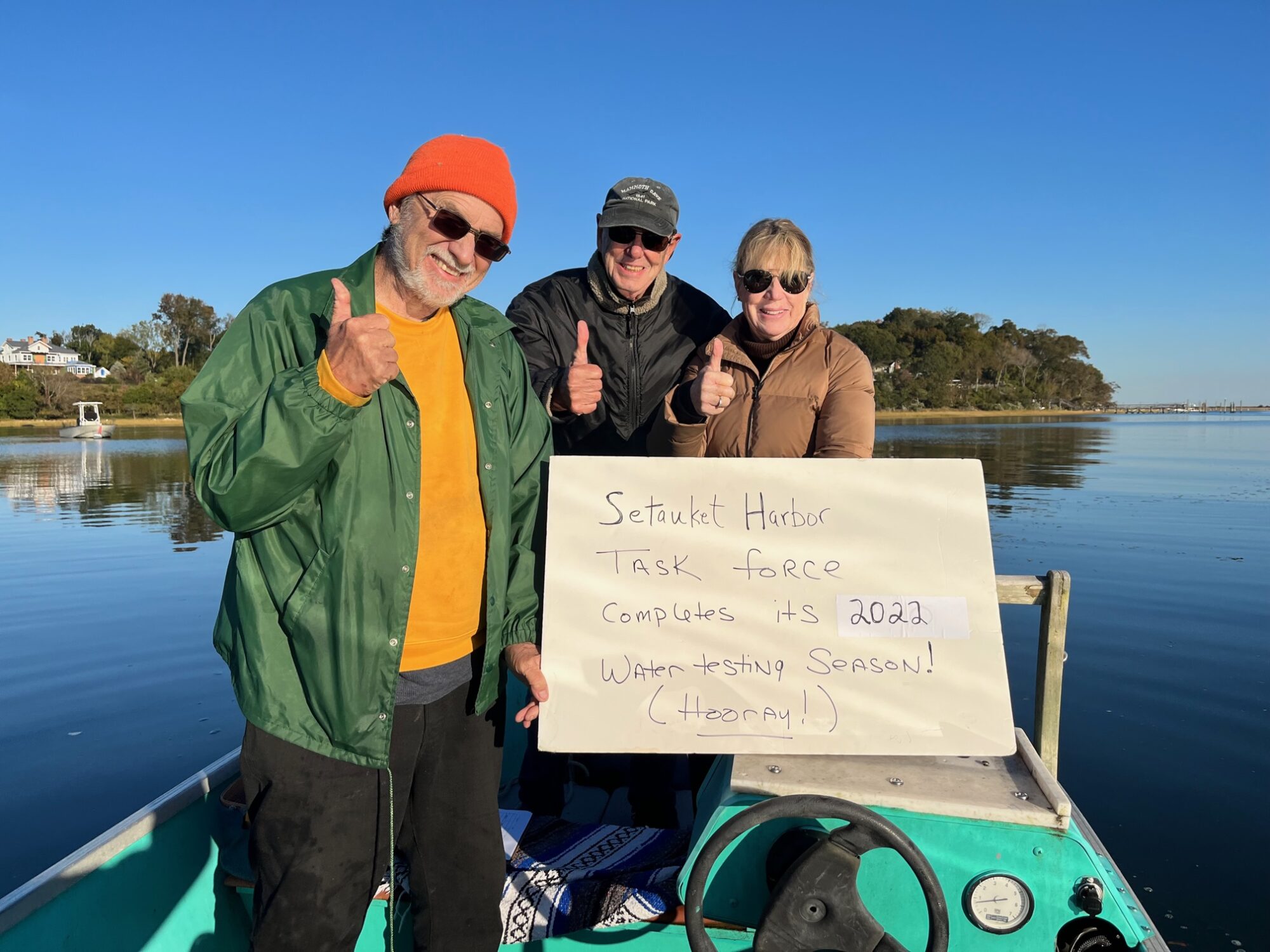

Every 10 days from mid-spring to mid-fall George Hoffman gets up early in the morning to meet three of his colleagues with the Setauket Harbor Task Force. At the harbor around 5:45 am, they join the captain of a small boat who takes them out on the water to monitor the ecological health of Port Jefferson and Setauket harbors.

Rain or shine, these volunteers navigate by GPS to their designated water quality stations to measure the water quality of their part of Long Island Sound. They take readings with a monitoring probe called a multiparameter sonde to help detect whether the impact of pollution from excess nutrients entering coastal waters as well as warm temperatures can lead to algal blooms and declines in oxygen. Low dissolved oxygen levels can result in hypoxia, or anoxia (no oxygen at all), making it difficult or impossible for fish and other aquatic life to breathe. Algal blooms can block the sunlight needed for eelgrass, an important underwater grass, to grow. Some harmful algal blooms can even be toxic to wildlife, humans, or pets.

In six years of monitoring, Hoffman recalls the task force members only missing one or two days of monitoring—due to heavy fog. The early morning alarm for monitoring–a requirement of the UWS that monitoring be conducted within three hours of sunrise when hypoxia is easier to detect—has not been a barrier for participation.

“People love to be out on the water and the earlier the better,” said Hoffman. “I thought at 5:30, 6 o’clock it would be a problem, but I never had anyone quit.”

Dedicated volunteers are not unique to Setauket and Port Jefferson harbors. The local group is part of the Unified Water Study, a soundwide monitoring program established by Save the Sound and financially supported by the Long Island Sound Study through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Since the UWS was created seven years ago as part of a handoff of a project called the Long Island Sound Report Card, it has grown into the largest community coastal water quality monitoring program on the Sound, and probably one of the largest in the northeast.

“I think what’s important about being a participating organization in the monitoring is that it really has given us a lot of credibility in terms of dealing with our local governments,” said Hoffman, a semi-retired legislative and local government official who helped start the task force in 2015 with a mission to reduce harmful bacteria in Setauket Harbor so that shellfish could once again be harvested. The task force has since expanded to include water quality issues related to the Unified Water Study. “I think a lot of people know that this is a large community of (groups) doing this on harbors on both sides of the Sound.”

Hoffman said the group’s ability to collect quality data has helped them gain the respect of local, state, and federally elected representatives, who in turn have helped to secure grants for public works projects to reduce the amount of polluted stormwater runoff entering the harbors. The Task Force is particularly concerned about polluted runoff and sediment from stormwater and sediment originating from Route 25A, a heavily used road near the shoreline.

The early morning alarm for monitoring–a requirement of the UWS that monitoring be conducted within three hours of sunrise when hypoxia is easier to detect—has not been a barrier for participation in Setauket, Port Jefferson or elsewhere.

“People love to be out on the water and the earlier the better,” said Hoffman. “I thought at 5:30, 6 o’clock it would be a problem, but I never had anyone quit.”

Since its 2016 start as a pilot project with three groups, the UWS has grown to 27 groups, ranging from all volunteer organizations like the task force to local government organizations and the Interstate Environmental Commission. The groups will monitor 46 embayments in 2023. Around the Sound, these water bodies have several names, including bays, harbors, coves, and inlets, and are associated with local references, such as Setauket Harbor, in the hamlet of East Setauket in the Town of Brookhaven on Long Island and Scott Cove in Darien, Connecticut.

As participating organizations under the UWS, programs like the Setauket Harbor Task Force agree to collect the same data using the same procedures through a Quality Assurance Project Plan. The QA plan is a requirement by EPA to receive federal funding, but it is also designed to assure that the data are scientifically trustworthy and can be used by decisionmakers. While the program’s data is standardized, each of the participating organizations have their own unique reasons to monitor their local waters.

Some of the local monitoring programs participating with the Unified Water Study have existed for decades. Many, such as the Coalition to Save Hempstead Harbor, and Harbor Watch, which monitors waters in Norwalk Harbor, have been collecting data that have led to successful efforts to reopen shellfish beds and remove sources of bacterial contamination. But prior to the UWS there has never been a regional approach to studying some of the most vexing problems affecting coastal waters, including the role nutrients play in impacting oxygenated waters.

“Nothing to this scale has everyone out in the water, same time in the morning, and using the same instruments, using the same standards collecting very important environmental health metrics, including dissolved oxygen,” said Peter Linderoth, Save the Sound’s water quality director, and its manager for the UWS since its start. “Just like we need oxygen to breath, animals in the water need oxygen.”

In contrast to the near-shore waters, the Long Island Sound Study has been funding coordinated efforts to monitor water quality in the “open water basins” and “narrows” of the Sound from New York City to eastern Connecticut and Long Island since 1987. Water quality data from that effort as well as from New York City were used by LISS, EPA, and the states of Connecticut and New York to help develop a plan to reduce nitrogen discharged from wastewater treatment plants. Water quality monitoring of the open Sound is ongoing in order to track the response of the nitrogen reduction plan as well as track other impacts, including increasing water temperatures, to the health of the Sound.

For the public and for policy makers, the results of the Unified Water Study monitoring efforts are available through the Long Island Sound Report Card, a project Linderoth works on with a team of scientists and UWS staff, and which is supported through The John and Daria Barry Foundation. Nearly a decade ago, Save the Sound took on the biennially produced report card from the Integration and Application Network, a program of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. IAN had received funding from the Long Island Sound Funders Collaborative to use existing water quality monitoring data to provide a report with letter grades to make it easier to evaluate the effects of restoration, conservation, and management on the Sound’s ecosystem. The letter grades were modeled after a similar report IAN developed for Chesapeake Bay and has since been replicated around the world. The initial report IAN produced for Long Island Sound with 2013 data focused on the Sound’s open water basins, but IAN also included grades for two bays as a model for future reports to have an expanded section for bays. When Save the Sound took over, however, it decided at first to remove the bays from the report card, and instead focus on creating and growing the Unified Water Study.

“(When) we became the group that releases the Long Island Sound Report Card we almost immediately took the embayments out of the report card and stopped extending the open water grades into bays and harbors,” said Linderoth. “We knew and know still that those waterbodies are incredibly relevant to the neighborhoods that surround them and to the communities that surround them, not just the specific neighborhoods. So, we needed to generate high quality comparable data to fuel bay grades for those bays and harbors because we see them as an incredibly important part of Long Island Sound of course and to really relay their conditions to lay people we needed to improve our monitoring program to get data to fill those gaps.”

The first report card with bay data was for 2020. Of the 50 bays and bay segments monitored by 22 groups, 56 percent received a grade of C, D, or F, and only six received a grade of A. The report highlighted the outsized impact that pollution from communities have on coastal waters, especially where tidal exchange from the ocean-influenced open Sound is low and pollutant loads from the rivers and streams are high. The grades showed that hypoxia was the biggest problem followed by excessive macroalgae or seaweed, a companion stressor.

Elected officials took notice. The report card played a role in congressional efforts to increase funding for Long Island Sound’s restoration. After the report card was released in October 2020 Connecticut Senators Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy cited the findings that more than half the bays received “low water quality scores” when it delivered a letter to the Committee on Appropriations and the subcommittee on Interior, Environment and Related Agencies that called for a “request for robust funding” for Long Island Sound.

As for the Long Island Sound Study, the Unified Water Study has helped to accomplish a long-term goal for developing a soundwide embayment monitoring network. In 2011 that became a priority when the LISS Management Committee requested proposals from scientists to evaluate existing embayment monitoring programs and provide recommendations on how to develop the network. At the time, the LISS management and scientific committees were seeking more information on the sources of nutrients coming from coastal lands that impacted the near shore, but also the open waters of the Sound. They desired to “improve access by Long Island Sound Study (LISS) partners’ to quality-assured embayment water quality monitoring data, and ultimately to improve scientific understanding for a more holistic management of the Sound.” The LISS committees also recognized the need to address pollution in the near-shore areas that had the most immediate impact on communities, including through beach closures, shell fisheries closures, and nuisance algae blooms. The resulting report, published in 2013, called for creating new water quality monitoring positions to help develop the network. It also included a proposed budget, but there were no funds at the time to implement the network.

Fast forward to 2023, and the data collected through the Unified Water Study is being used by Long Island Sound Study’s partners. CT DEEP, for example, is using data to assess whether near shore areas are meeting the state standards for dissolved oxygen levels. Data from the near shore areas through the UWS also will be used to supplement CT DEEP’s data collection effort designed to develop scientific models for establishing new targets to reduce nutrients in Connecticut’s priority bays and harbors. CT DEEP anticipates that once the models are completed and corrective actions are implemented, the frequent monitoring of bays by the UWS groups will also be valuable to help track the response of the system to change over time.

Kelly Streich, a CT DEEP analyst working on the model, said that having a quality assurance plan was essential for the state’s ability to use data collected by community-based organizations.

“That makes a big difference.” said Streich. “We know it is quality assured, we know that the UWS monitoring groups were trained, and the data is validated through the UWS program before it is made available for use by Save the Sound.”

You can request the 2022 Long Island Sound Report Card, and download previous report cards, on the Save the Sound website. Long Island Sound Report Card – Save the Sound

Ten years ago, a Long Island Sound Study-funded report outlined steps to establish a soundwide network of community-based groups monitoring for near-shore waters. It also highlighted a major challenge toward its creation.

Community-based volunteer groups, said the study’s authors, were highly supportive of joining a network, but “this is dependent upon the provision of necessary resources in the form of training, equipment and supporting funds.”

Save the Sound, which eventually took on the role of creating the network through the Unified Water Study, has met that challenge through its Equipment Loan Program.

Originally run by Harbor Watch, an early member of the Unified Water Study, the Equipment Loan Program was taken over by Save the Sound in 2017 at a time when about 12 groups were participating. Managed by Elena Colon, the program provides equipment ranging from sophisticated water quality sensors to supplying data sheets and buckets. The most unusual loan is a boat, an Amesbury Dory, donated to Save the Sound from a supporter, and provided to the Bronx River Alliance on loan for six months a year to conduct water sampling on the Bronx River, including an outermost station near the Western Narrows of Long Island Sound.

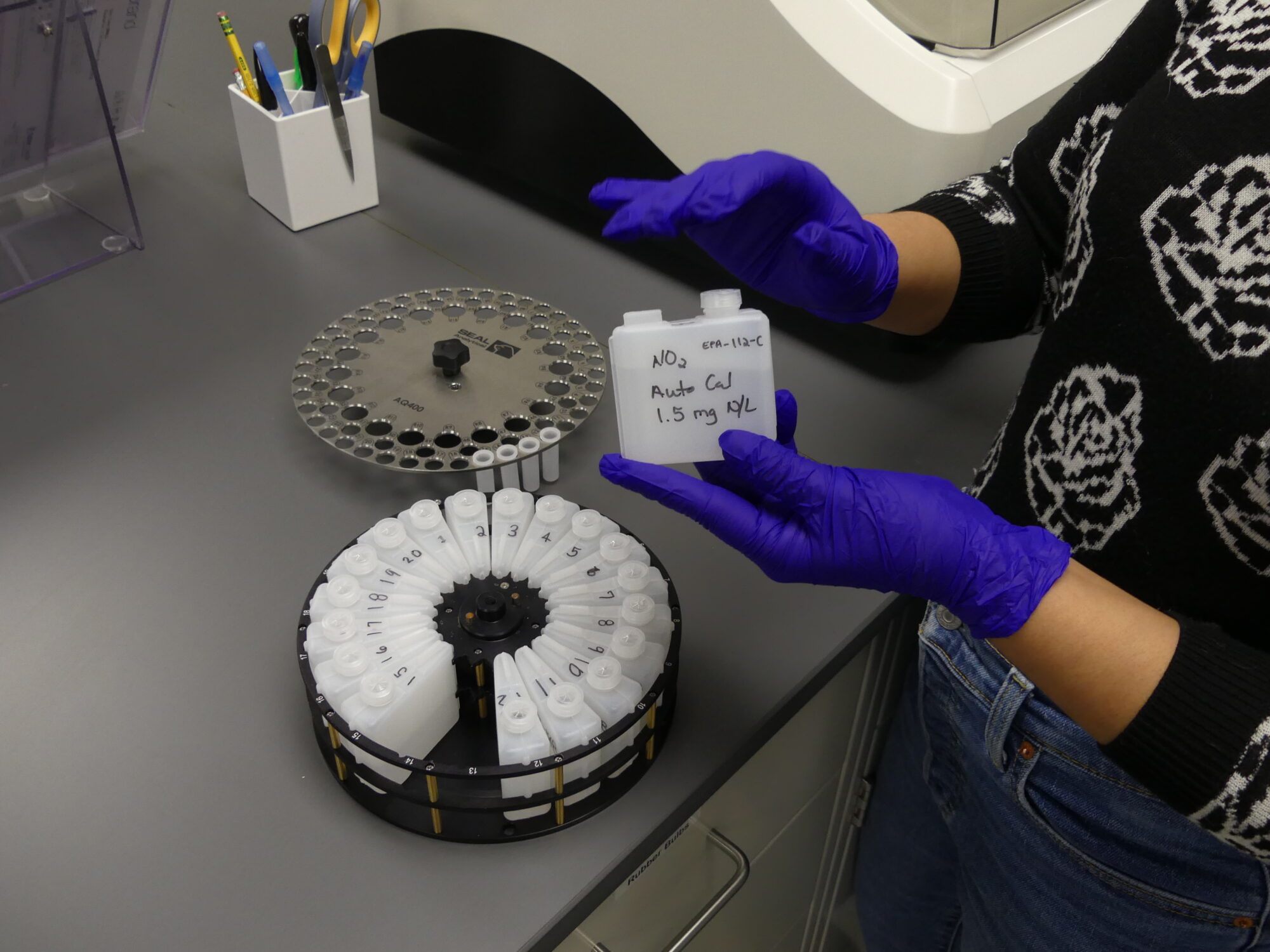

During the monitoring season, the groups collect data, including readings from a device with a sensor called a multiparameter sonde that measures dissolved oxygen, temperature, water turbidity, and chlorophyll a (a pigment in plants that helps in coastal waters to indicate the abundance of microalgae and its need to use nitrogen to grow). It also collects physical samples of chlorophyll a. At The John and Daria Barry Foundation laboratory, part of Save the Sound’s New York office in Larchmont, Colon analyzes the samples and ensures that all the data that has been collected is validated so it can be used for scientific study and for reports such as the Long Island Sound Report Card. Thanks to funding from the Long Island Sound Study the supplies have been able to keep pace with the growth of the UWS, which will monitor 46 embayments through 27 groups in 2023.

Peter Linderoth, director of water quality for Save the Sound, describes the Equipment Loan Program as a game changer in helping UWS expand around the Sound.

“With the equipment loan program, Elena and the team are getting this equipment all the way out to eastern Connecticut and Long Island and west to New York City,” he said. “It really is an impressive feat.”

Through funding from The John and Daria Barry Foundation, Colon also is now able to conduct in-house analysis of the physical samples instead of contracting out to a third party laboratory, which has often resulted in long wait-times to get results back. A new discrete analyzer will be particularly useful for “tier 2” monitoring groups, a subset of the UWS monitoring groups that have the capacity to collect samples of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other substances that provide more detailed measures of the Sound’s water quality. The in-house work will save money, and the faster turnaround should help the monitoring groups get information faster to make corrections if necessary and “fine-tune” their sampling techniques.

Each April, Colon and Linderoth also provide training for the groups on how to use the equipment and how to collect data that meets the program’s Quality Assurance Project Plan. Colon also is available during monitoring season from May to October to answer any questions.

“I am basically a built-in tech support for everyone,” she said. “So, I make sure that all of the equipment is running. I make sure to order, purchase and replenish inventory. I make sure that when any of the groups run into problems I am there, and I am going to fix it for them. “

Colon also has noticed that the groups are not just talking to her. They are getting to know each other through training sessions, conferences, and video chats, and exchanging information and collaborating to improve their skills.

“There is something to be said when you are all part of the same study of this scale,” said Colon. “It is just kind of like you are all in the trenches together. It is so great (for them) to be able to exchange stories. ‘How did you do that?’ ‘How was it for you?’ It really brings people together.”

As part of International Horseshoe Crab Day on June 20, Sacred Heart University and Project Limulus will be hosting a horseshoe tagging event and talk in honor of Jennifer Mattei, a long-time professor at Sacred Heart University who died in December at the age of 62. Mattei’s projects to restore shoreline habitats and protect wildlife, including the horseshoe crab, have played an outsized role in Long Island Sound restoration efforts.

The event will be held at noon at Stratford Point in Stratford, CT, and is part of a series of horseshoe crab events being held in Connecticut this month. They are timed to the season when horseshoe crabs arrive on the beaches from the Sound to spawn. Information about the events, including community monitoring to count horseshoe crab populations, are on the Sacred Heart University website.

Mattei established Project Limulus in the 1990s to conduct research, monitor populations, and raise awareness of the American Horseshoe Crab, Limulus polyphemus in Latin. They are a vitally important species to coastal ecosystems that are older than the dinosaurs, but are now in decline.

Globally, Mattei served as a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Horseshoe Crab Specialists Group working to protect and conserve horseshoe crabs. Locally, her work at Project Limulus helped in efforts to tag over 98,000 horseshoe crabs to better understand their patterns of movement and track their abundance. She was an early supporter of community science by inviting volunteers to participate in population counts of the horseshoe crabs on local beaches and reporting the tagged horseshoe crabs they saw to Project Limulus. Through this initiative, she also gave public lectures on the importance of the species to the ecosystem to thousands of people.

Mattei also was a well-respected teacher at Sacred Heart who played a key role in developing the school’s coastal & marine science major, and she chaired the biology department from 2003 to 2009. She mentored dozens of undergraduate and graduate research students, and recruited many students to participate in her research. Collectively, her students delivered more than 75 presentations at internal, national and regional research conferences and received at least five awards. Many of her students went on to pursue careers in science and education. Citing her roles as a dedicated teacher, Sacred Heart University this year awarded her the status of professor emerita.

“Jennifer was extremely passionate about the conservation and restoration of the natural world and about inspiring and educating the next generation of scientists,” said Jo-Marie Kasinak, a former student of Mattei who is now the director of Project Limulus. “She was a huge supporter of undergraduate research, and developed courses that allowed her students to participate in scientific research and present their findings at local conferences.”

Mattei received her Ph.D in Ecology and Evolution at Stony Brook University in 1994. Her first project that received wide attention occurred when she was a postdoctoral researcher at Rutgers University in the 1990s. She was part of a team of scientists to successfully restore coastal woody shrub habitats on top of closed sections of the Fresh Kills landfill in Staten Island, the largest landfill in the U.S. at the time. Mattei continued her Fresh Kills research with a five-year National Science Foundation grant to study the plant and animal interactions at the site after she joined the Sacred Heart faculty in 1997, the same year she started Project Limulus.

In 2013, Mattei started a new project that bridged a gap between restoring and protecting habitats for wildlife such as horseshoe crabs and responding to the impact of sea level rise and climate change along the coast. With support from a Long Island Sound Futures Fund Grant, Mattei conducted a pilot project to install concrete reef balls just off the shoreline at Stratford Point. The reef balls, which are pocketed with holes, are normally used to mimic natural oyster reefs. They provide a structure for oysters to attach to and grow. But in this project Mattei focused on using the reef balls to dampen the impact of strong waves from eroding the shoreline and drowning a newly planted saltmarsh grass restoration. The project succeeded, indicating that nature-based “living shoreline projects” can be used to adapt to storm surges and higher tides that are likely to occur due to climate change. Since Mattei initiated the concept more than a dozen living shoreline projects in Connecticut and New York portions of the Long Island Sound watershed have been completed, are underway, or are planned.

While she published many academic papers, Mattei focused a lot of her attention to educating the public about the beauty of nature near where they lived. In an article that appeared in the fall 2022 Sacred Heart University magazine, Mattei expressed to the magazine’s readers that environmental preservation in the age of climate change impacts should be considered the highest priority for everyone’s involvement. She wrote optimistically that the scientific community will successfully address this problem, but needed the involvement of individuals as well, even if it starts modestly through simple actions such as planting a tree in a backyard.

“Certain as our dependence on the natural world is, it’s a wonder there is any question over what a priority its preservation should be,” she wrote. “Environmental stewardship is not a hobby or a ‘pet project.’ It’s an existential imperative.”

Kasinak hopes people remember Mattei’s passion for protecting the environment and her tenacity in fighting for what she believed. “She had a way of bringing out the best in those around her and worked to help them reach their full potential,” said Kasinak. “She was instrumental in shaping me into the scientist and educator I am today.”

More on Mattei’s work

LISS Project Limulus slideshow (a photographer for the Long Island Sound Study spent a day with Mattei and her students to watch horseshoe crab monitoring.

Stratford Point Living Shoreline Project

“Our Natural World” Dr. Mattei’s last article which appeared in the Sacred Heart University magazine.

To honor Dr. Mattei’s legacy, the Sacred Heart University Department of Biology is creating The Jennifer H. Mattei Scholarship for Undergraduate Research. This scholarship will provide undergraduate students with stipends to conduct research in Connecticut with a biology faculty member in the fields of ecology, coastal management and restoration or other biological studies involving Long Island Sound, and to support Project Limulus and related ecological research. The University is reaching out to the community, through a crowd-funding site, to establish an endowed fund in Jennifer’s memory that will exist in perpetuity.

Left to right: Tom Mohrman (Maidstone Landing Association), Corey Humphrey (Suffolk County Soil & Water Conservation District), Kathleen Fallon (NYSG), Suffolk County Legislator Stephanie Bontempi, Elizabeth Hornstein (NYSG), Village of Port Jefferson Trustee Rebecca Kassay, Mark Lowery (NYSDEC), Suffolk County Legislator Sarah Anker, Suffolk County Legislator Kara Hahn, Suffolk County Legislator Al Krupski, Barbara Kendall (NYSDOS), Ryan Porciello (NYSDEC), Alexa Fournier (NYSDEC), Sarah Schaefer-Brown (NYSG)

Two forums — one held at Locust Valley Library in Nassau County on May 4 and another at the Port Jefferson Village Center in Suffolk County on May 10 — brought together 90 attendees, including state and local decision makers, municipal state, and other stakeholders, working to address coastal erosion along the Long Island Sound shoreline.

Participants shared information on best practices, discussed challenges, and identified opportunities to increase resilience, all in an effort to enhance coordination across communities.

Panelists highlighted strategies and options to address coastal erosion, discussed the Coastal Erosion Hazard Areas Program, local codes, updated New York State sea level rise projections and more.

During small group discussions, attendees delved into:

• how to better educate private property owners who live on the shore or who are buying property on the shore

• how county, state and federal agencies can better support municipalities and communities who are dealing with shoreline erosion

• how to balance protecting coastal habitats with protection of coastal communities and infrastructure.

Over the next few months, organizers will review the feedback from the small group discussions and follow up with partners on next steps.

Hosted by New York Sea Grant and Long Island Sound Study through the Sustainable and Resilient Communities initiative, these forums were made possible thanks to partnerships with Nassau and Suffolk Soil and Water Conservation Districts and Suffolk County Legislators Sarah Anker, Stephanie Bontempi, Kara Hahn, and Al Krupski. They were led by two Long Island Sound Study extension professionals for sustainable and resilient communities: Elizabeth Hornstein and Sarah Schaefer-Brown, both of New York Sea Grant.

For more information about the forums, including requesting the presentations, contact Hornstein, the Suffolk County extension professional at elizabeth.hornstein@cornell.edu or Schaefer-Brown, the Nassau County extension professional, at sarahschaefer-brown@cornell.edu.

It’s worth celebrating these plants that serve as important habitat for many wildlife species. Wetland plants such as salt marsh grasses have roots that tolerate and thrive in watery soil, including along the brackish waters of Long Island Sound. They act as a buffer to stormy seas, slow shoreline erosion, and filter pollutants.

Since 1998, the Long Island Sound Study and its partners have restored over 1,100 acres of tidal wetlands. Learn more at the LISS ecosystem targets and supporting indicator microsite.

Wetlands also are an important component of living shoreline projects, which are nature-based solutions to protect coastal areas from the impacts of sea level rise and climate change. Learn about living shoreline projects in Long Island Sound in the Thriving Habitats section of the Long Island Sound Study website or view a living shorelines story map produced by the CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

Wetlands are both an effective and economical way to enhance community safety while improving quality of life. American Wetlands Month was established in 1991 by EPA and its partners. Find out more why it’s worth celebrating in May or any time of the year on the EPA website.

See the value of wetlands at Sunken Meadow State Park in Long Island

Check Out Virtual Tour of Long Island Sound Habitats and Teacher Webinar

The COE Plan sets out to align and coordinate Communication, Outreach, and Engagement efforts of LISS staff and partners over five years. The Plan provides clear goals, actions, and metrics designed to enhance engagement among LISS’s current – and prospective – partners, enabling them to work in a more coordinated manner, better leverage their respective skills, and expand reach to individuals, organizations, and communities throughout the Sound watershed.

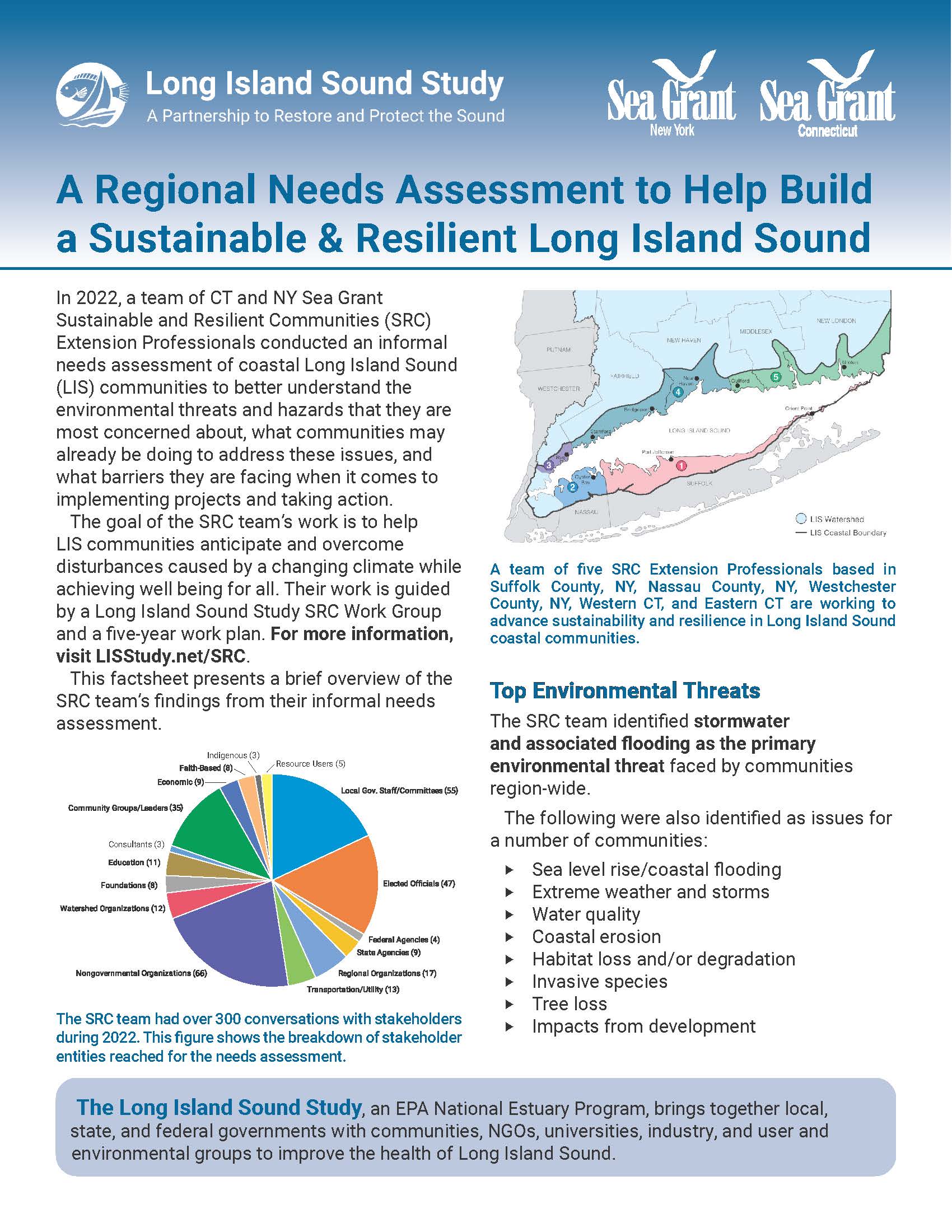

The fact sheet highlights a needs assessment of coastal Long Island Sound communities to better understand the environmental threats and hazards that they are most concerned about, what communities may already be doing to address these issues, and what barriers they are facing when it comes to implementing projects and taking action. The assessment was conducted by the Connecticut and New York Sea Grant Sustainable and Resilient Communities extension professionals. Download fact sheet.

Connecticut Sea Grant is excited to share openings for three extension positions. The positions are:

- Extension educator—nature-based approaches to resilience. The successful candidate will work in collaboration with federal and state agencies, municipal entities, and communities, along with partner organizations, to foster and improve exchanges of knowledge to better identify the diverse needs of communities, including their response to increasing threats to coastal resources associated with climate change, and to increase the public’s understanding of changing conditions, hazards, and related impacts. See https://academicjobsonline.org/ajo/jobs/24454.

- Sustainable and resilient communities assistant extension educator. The successful candidate will coordinate and collaborate with the four other Extension professionals in CT and NY to efficiently and effectively achieve the goals of the LISS Sustainable and Resilient Communities five-year work plan. See https://academicjobsonline.org/ajo/jobs/24455.

- Long Island Sound Study outreach coordinator. The successful candidate will work to increase appreciation, stewardship, awareness, and understanding of Long Island Sound and efforts to restore and protect it. Special emphasis is on educational programs for diverse communities and stakeholders that lead to the protection and restoration of Long Island Sound’s natural resources. See https://academicjobsonline.org/ajo/jobs/24452.

This entry originally appeared on the Connecticut Sea Grant website.

The Long Island Sound Futures Fund 2023 Request for Proposals is Now Open!

Proposal Deadline: Wednesday, May 10, 2023

The request for proposals is available on the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation website.

There will be a total of $10 million for environmental grants in the Long Island Sound watershed (CT, MA NH, NY, VT).Grant range $50k-$1.5m.

Types of Funding: $50k-$1.5m for “shovel-ready” projects $50k-$500k for planning…watershed, resilience, feasibility, suitability/ alternatives analyses, site assessment/conceptual design, final design/permits

Geography & Funding Priorities? See the Interactive Sound Watershed Map

Connecticut and New York grants will be available for

- Clean Waters and Healthy Watersheds – projects to reduce nutrient loading, combined sewer overflows, stormwater runoff, and nonpoint source loading.

- Sustainable and Resilient Communities – projects to increase the knowledge and engagement of the public in protection and restoration of the Sound; or projects that combine resilience, community, and conservation goals

- Thriving Habitats and Abundant Wildlife – projects to restore coastal habitats and foster fish and wildlife in the coastal boundaries of CT and NY

Long Island Sound Watershed (non-coastal CT, MA, NH and VT) grants available for projects to prevent nutrient/nitrogen loading such as riparian, freshwater wetland & in-stream restoration, agriculture, wastewater treatment facility retrofit etc.

Want project idea feedback? Reach out to LISFF23@nfwf.org.

The deadline to submit project ideas is April 14, 2023. NY and CT Coastal: Reach out to a Long Island Sound Study Extension Professional MA, NH, VT & non-coastal CT: Reach out to Courtney@throwe-environmental.com Register for one of 12 Workshops or Webinars. Check out the RFP for the list. Grant-writing Assistance Program? Questions?…LISresilience@gmail.com

More information:

Robert Burg, Long Island Sound Study, rburg@longislandsoundstudy.net

Paul C. Focazio, Communications Manager, NYSG, paul.focazio@stonybrook.edu, P: (631) 632-6910

Judy Benson, Communications Coordinator, CTSG, judy.benson@uconn.edu, P: (860) 287-6426

Soundwide (March 2, 2023) – Long Island Sound water quality, salt marsh and public beach characteristics will be examined by marine and social scientists in nine research projects awarded funding by the Connecticut and New York Sea Grant programs (CTSG and NYSG respectively) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Long Island Sound Study (LISS) Research Grant Program.

These new projects, which seek information that can be used to improve the conditions of the estuary for humans and wildlife, are being supported by $4.2 million in federal funds. That will be supplemented with matching funds of $2.1 million, for a total research package of more than $6.3 million.

The projects will be conducted over two years beginning this spring. The results will build on the substantial body of research funded through the LISS Research Grant Program administered by CTSG and NYSG since 2008 which has contributed to improved understanding and management of this nationally recognized estuary. Cumulatively, this represents the largest research investment in the Sound, which has been designated an estuary of national significance and one of the most valuable natural resources for both states.

The four CTSG-administered projects are:

- “Testing the effects of vegetation on saltmarsh ecology, services and restoration success: from microbial ecology and biogeochemistry to wildlife conservation,” will be led by UConn professors Christopher Elphick, Beth Lawrence and Ashley Helton, along with Blaire Steven of the CT Agricultural Experiment Station and Min Huang of the CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. By creating sediment mounds of varying elevations planted with various species at different densities at Great Meadow Marsh in Stratford, the researchers seek to develop an interdisciplinary understanding of how marsh restoration efforts impact the functioning of these ecosystems and their value for wildlife.

- “Tracking pathogen pathways and fecal bacteria patterns for public beaches suffering with poor water quality grades and closures,” will be led by UConn Professor Michael Whitney with Peter Linderoth of Save the Sound. The researchers will analyze patterns of fecal indicator bacteria in water samples from Green Harbor Beach in New London and Rocky Neck State Park in East Lyme. Because of high bacteria levels, these two public beaches are among the most frequently closed or under swim advisories in the state of Connecticut. The work will include efforts to identify bacteria pathways and public outreach about water quality issues.

- “Assessing temperature mediation of PFAS impacts on coastal fish fitness to inform environmental management,” is being led by professors Maria Rodgers of North Carolina State University and Jessica Brand, Daniel Bolnick, Kat Milligan-McClellan and Milton Levin of UConn. The researchers will examine concentrations of PFAS (poly- and per-fluoroalkyl substances) at different water temperatures in fish populations downstream from the outfalls of public sewage treatment plants. The results will quantify how fish can be expected to respond to exposure to these “forever chemicals” in the Sound over the next five decades.

- “Assessing the impacts of warming and planting strategy on the resilience of restored salt marshes to improve restoration efficacy,” will be led by Sarah Crosby of The Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk, along with A. Randall Hughes and Nicole Kollars of Northeastern University, Nicole Spiller of Harbor Watch and Earthplace, and LaTina Steele at Sacred Heart University. By enclosing sections of salt marshes within open chambers to increase interior temperatures, the researchers will assess the expected effects of warmer temperatures associated with climate change. The work will include plantings of southern-sourced marsh grass (Spartina) strains to determine impacts on future resilience, and an examination of the genetic mixing of these salt marsh strains to enhance the success of restoration efforts.

The five NYSG-administered projects are:

- “Using geohistorical baselines to assess responses of benthic macroinvertebrate communities to the nitrogen TMDL management intervention in Long Island Sound,” is directed by Gregory Dietl of the Paleontological Research Institution.Scientists will look at the remains of mollusks buried beneath the seafloor to understand past ecological conditions in the Long Island Sound (LIS). The molluscan geohistorical record could provide location-specific information about levels of nitrogen relevant for decades-long time periods that is not available from any other source.

- “Coupled prediction of residential fertilizer use and nitrogen loads to Long Island Sound: An integrated targeting tool for nitrogen-reduction behavior change campaigns,” is led by Robert Johnston of Clark University, along with David Dickson and Jamie Vaudrey of the University of Connecticut, David Newburn of the University of Maryland, Qian Lei-Parent of the University of Connecticut, and Haoluan Wang of the University of Miami.This project will use a survey of households to predict residential fertilizer lawn use for the coastal counties and municipalities across the LIS watershed. A model combining this information with water quality data will be used to inform prospective behavior-change campaigns to identify and prioritize the areas or types of households that would have the greatest impact on reducing nitrogen from lawn fertilizer and its impact on the Sound.

- “Actionable satellite water-quality data products in LIS for improved management and societal benefits,” is headed by Maria Tzortziou of the City College of New York, along with Joaquim Goes of Columbia University and Melanie Abecassis of the University of Maryland College Park.Human-caused climate change as well as other anthropogenic factors can intensify harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the LIS. Observations of the entire ecosystem, over different seasons and across a range of conditions, including during extreme weather events, can be obtained from satellite data. This work will provide actionable information for water resource management, policy, and decision-making.

- “Evaluating changes in suitable habitat and distribution of cold- and warm-adaptive fish species in a changing Long Island Sound to inform ecosystem-based management,” is led by Yong Chen of Stony Brook University, along with Kurt Gottschall of the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, Kim McKown, and John Maniscalco, at New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Conditions in the LIS have been shifting due to climate change, affecting water temperature, acidity, oxygen levels, and incidence of HABs. The scientists will evaluate these shifting conditions on the distributional changes of warm-adapted and cold-adapted species of fish in the Sound.

- “Equitable access to Long Island Sound waterfront and beaches through on-demand mobility,” is led by Anil Yazici and Elizabeth Hewitt of Stony Brook University. Some communities on Long Island do not have the mobility means to use and appreciate the LIS waterfront. Project leaders are designing and piloting on-demand shuttles that will facilitate equitable public access to the LIS waterfront. The team will survey users of the shuttle service to identify changes in attitudes toward the LIS environment.

In their words: Long Island Sound Research Projects:

From Sylvain De Guise, director of CTSG: “The continued partnership between Sea Grant programs and EPA will support a nice diversity of innovative and ambitious research projects to benefit both people and ecosystems of Long Island Sound, for mutual benefits—a wise investment, in my opinion.”

From Syma Ebbin, research coordinator for CTSG: “This competition was the largest ever administered, allowing the program to support these diverse, high-quality proposals, all with the capacity to enhance Long Island Sound’s management, health and public benefits.”

From Becky Shuford, director of NYSG: “New York Sea Grant is proud to continue this long-standing partnership with Connecticut Sea Grant and the EPA Long Island Sound Study. This year was the largest research competition to date resulting in the selection of nine excellent and diverse studies that will address priorities related to historical and current water quality conditions, habitat and fisheries health and restoration, and Sound access. The results will have direct benefit to the communities, coasts, critters, and waters of the Long Island Sound Estuary.”

From Lane Smith, research coordinator for NYSG: “This cohort of new research will build on the growing legacy of impactful research that benefits the Long Island Sound and its coastal communities. This continues the fruitful partnership between Sea Grant and the EPA Long Island Sound Study that benefits the LIS ecosystem.”

From David W. Cash, EPA New England regional administrator: “The Long Island Sound estuary is an essential ecosystem that supports communities, economies, and habitats across the region. I’m pleased to say these diverse and innovative Sea Grant projects include a focus on improving the Sound’s water quality, mitigating the effects of climate change, and helping local communities receive more equitable access to the Sound.”

From Lisa F. Garcia, EPA Region 2 regional administrator: “The Long Island Sound is in the center of one of the most densely populated coastlines in the country. This investment will help Long Island Sound communities combat sources of pollution that lead to closing public beaches or contaminating local fish. It will also help communities improve efforts to restore wetland habitat and increase resiliency to climate change by understanding the effects of sea level rise and warming temperatures on valuable marsh habitats. This funding will advance ecological research and play a critical role in improving water quality and reducing pollution, providing lasting results for the wildlife and wetlands in the Sound for years to come.”

Descriptions of Long Island Sound Study research grants since 2000 with final research reports are available on the Long Island Sound Study website.