Each year the Long Island Sound Study develops a Work Plan as part of the National Estuary Program that outlines the work being done with EPA funds to help achieve the goals of the Study’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan. The 2021 Work Plan describes the LISS activities planned with 2021 federal funding for Oct. 1, 2021 to Sept. 30, 2022. It also highlights projects undertaken from Oct. 1, 2020 to Sept. 30, 2021 with 2020 federal fiscal funds.

Download LISS FY2021 NEP Work Plan to read the document.

Returning the Urban Sea to Abundance, a report submitted to the US Congress, summarizes the progress made from 2015-2019 in restoring the health of Long Island Sound. It provides an assessment of the first five years of action by the Long Island Sound Study (LISS) under the 2015 Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP), which established general goals and measurable targets to restore the health of the Sound by 2035.

Two Long Island Sound scientists with international reputations in their fields have retired from the Long Island Sound Study committee they helped to reestablish back in 2002.

Charles “Charlie” Yarish and Johan “Joop” Varekamp announced their retirements in emails sent to members of the Science and Technical Advisory Committee in February.

“Having participated in the LISS ever since its inception, and being the Connecticut Co-Chair of the STAC for many years, I think it is about time to leave it to others in CT to become active participants on the STAC,” said Yarish, a professor emeritus at the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Marine Sciences at University of Connecticut who had served as co-chair from 2002-2012. “I have seen some great accomplishments of the LISS, which is because of the dedicated leadership of so many people.”

“For me the time is also here (like Charlie Yarish) to retire formally from the STAC,” said Varekamp, who also will be retiring as a professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Wesleyan University this summer. In his email to the STAC, Varekamp –whose research in Long Island Sound has focused on understanding the environmental history of Long Island Sound through the use of sediment core records—noted the recent paper by UCONN scientists showing the relationship between a successful management program to reduce nutrient pollution and improved water quality in the Sound. “It is great to see that much of the work of the last 30 years is yielding results and a better understanding of the functioning of LIS,” he said.

The STAC was originally founded as the Technical Advisory Committee in 1986 to help direct monitoring and research to characterize water quality issues in Long Island Sound. In 1992, it was reformed into technical work groups to develop management recommendations for the Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP). It stopped functioning until 2002, when it was reestablished as the STAC to provide a forum to exchange ideas and make recommendations for funding research and determining key issues for the LISS. The committee is made up of a core group of, engineers, scientists, researchers, agency managers, and other professionals.

Besides serving on the STAC, Yarish’s involvement with the LISS has included co-editing a book synthesizing decades of Long Island Sound research titled Long Island Sound: Prospects for the Urban Sea (Springer 2014). At UCONN, he developed an internationally known Seaweed Marine Biotechnology Laboratory for seaweed research and development, and in 2019 received the Phycological Society of America’s Award of Excellence for his sustained scholarly contributions in, and impact on, the field of phycology (the study of seaweeds and algae) over his career. In 2009, he helped to co-sponsor a LISS-funded international conference on nutrient bioextraction – a method to remove excess nutrients in coastal waters through the harvesting of shellfish and seaweed, which take up nutrients such as nitrogen for their growth. The conference helped to launch several bioextraction pilot projects in the Sound to study the benefits of bioextraction in reducing nitrogen pollution and has inspired aquaculture farmers and NGOs to grow shellfish and seaweed in part to help improve water quality.

For the LISS, Varekamp wrote the chapter on metals, organic compounds, and nutrients for the Long Island Sound synthesis book. He also received one of the first research grants in the Long Island Sound Research Grant Program in 2000 in a project titled Environmental Change in Long Island Sound over the last 400 years, which included studying sediment core records to get a better understanding of hypoxia (conditions of low dissolved oxygen) in Long Island Sound, contaminants such as mercury, and global warming. Varekamp’s Long Island Sound research, which investigates a historical record spanning over 1,000 years, has helped researchers and agency managers gain a better understanding of pollution and warming trends in the Sound by learning how it functioned before the pre-colonial and pre-industrial eras. Besides his work in the Sound, Varekamp also is internationally known for his research on volcanic lakes and how volcanic lakes related to volcanic activity and their hazards. In 2019 he was awarded the prestigious Kusakabe Award by the IAVCEI Commission on Volcanic lakes.

Yarish on-line:

- Long Island Sound Study web pages on the International Bioextraction Workshop. Click here. (https://longislandsoundstudy.net/our-vision-and-plan/clean-waters-and-healthy-watersheds/nutrient-bioextraction-overview/nutrient-bioextraction/)

- Yarish’s Long Island Sound nutrient bioextraction pilot projects. Click here.

- Yarish being interviewed on 60 Minutes describing the benefits of seaweed in improving water quality. Click here.

- Current Yarish research with the US Department of Energy, including Integrated Seaweed Hatchery and Selective Breeding Technologies for Scalable Offshore Seaweed Farming with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Techniques for Tropical Seaweed Cultivation and Harvesting with the Marine Biological Laboratory at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Click here and here.

Varekamp on-line

- Varekamp’s Long Island Sound Study-funded research on the environmental history of Long Island Sound. Click here and here.

- Wesleyan University blog post discussing Varekamp’s research on volcanic lakes Click here.

- Article by Varekamp and his daughter, Daphne, in 2006 titled Click here. (Varekamp’s research has explored the connection between the colonial and industrial eras of the Sound with its physical and environmental history and how development has impacted water quality, including this article that explores how climate change helped lead to the Dutch exploration and settlement of Long Island Sound in the 17th century).

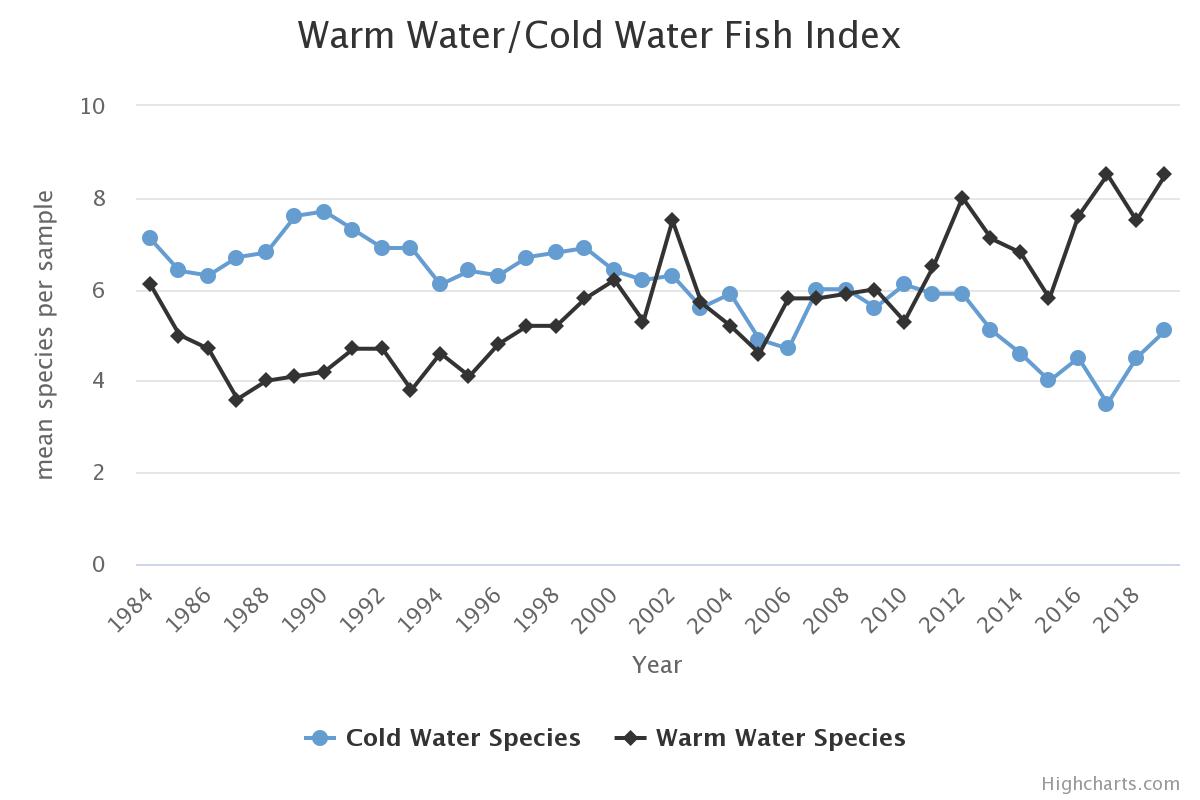

While the fish population and the biomass of the Long Island Sound fishery have remained stable over decades, the types of fish are changing. As Long Island Sound’s water temperature increases, the number of fish species that thrive in warmer temperatures is on the rise, while the number of fish species preferring colder temperatures is declining.

Learn More through our Long Island Sound Ecosystem Target and Supporting Indicators web pages:

- Warm Water/Cold Water Fish Index. The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection groups species counted in the Long Island Sound Trawl Survey by their temperature tolerance as an indicator of climate change. This indicator shows that fish with greater tolerance to warmer temperatures are increasing, while fish that prefer colder temperatures are declining.

- Water Temperature. LISS has compiled datasets for this indicator showing water temperature trends in the Long Island Sound region since 1960.

- Game Fish. CT DEEP’s fish trawl survey tracks fish populations in Long Island Sound of the most popular fish caught by anglers. Populations of some of them, including Sea Bass and Winter Flounder, have been affected by temperature trends.

- Lobster Abundance. Warming temperatures are considered to be an important factor in the significant decline of the lobster population in Long Island Sound.

- Finfish Biomass and Species Richness Indices. This indicator shows that the Sound fish productivity (based on fish biomass) and species diversity have remained high since the two surveys survey started in 1984 and 1992.

And here’s a video on fish and climate change in the Hudson River

CONTACTS:

- Mikayla Rumph, U.S. EPA Region 1 (New England), 617-918-1016, Rumph.Mikayla@epa.gov

- John Senn, U.S. EPA Region 2, (NY/NJ/PR/USVI), 212-637-3662, Senn.John@epa.gov

Long Island Sound Watershed, New York (May 26, 2021) – As summer approaches, EPA officials are highlighting water quality improvements in Long Island Sound resulting from almost 50 million pounds of nitrogen pollution kept out of the Sound each year. A peer-reviewed study from the University of Connecticut published earlier this year showed that improved water quality can be attributed to successful programs in Connecticut and New York to upgrade wastewater treatment plants to remove nitrogen before treated sewage is discharged into the Sound.

These two state-led programs have reduced millions of pounds of nitrogen pollution from being discharged into Long Island Sound, which has led to increased oxygen concentrations in the Sound in the summer months and, as a result, improved ecological conditions for fish and other organisms.

“Water quality in Long Island Sound is improving thanks in large part to dramatic reductions in nitrogen pollution, which is great news for the Sound’s ecosystem and local communities,” said EPA Region 2 Acting Regional Administrator Walter Mugdan. “Here in New York, we have seen tremendous success in New York State’s work to keep nitrogen from reaching the Sound in treated sewage, which will have a lasting impact for years to come.”

“This study is good news for the Long Island Sound and its neighboring communities, as it highlights successful actions taken to improve the Sound’s water quality,” said EPA New England Acting Regional Administrator Deborah Szaro. “Using science to inform our decisions, while maintaining a strong partnership with the states of Connecticut and New York, helps us continue to protect and restore the Sound, as well as plan for future action.”

Every summer, concentrations of dissolved oxygen (DO) in Long Island Sound waters decline to levels that are unhealthy for fish and other aquatic life. Low levels of DO, known as hypoxia, occur during the summer in the bottom waters of the western portion of the Sound, sometimes extending into central portions of the Sound. Hypoxia results when excess nitrogen fuels the growth of algae blooms. Bacteria that then feed on the algae deplete the water of oxygen. As a result, mobile organisms such as fish, crabs, and lobsters are forced to flee the area in search of healthier waters. Species that cannot move away, such as shellfish or worms, are harmed or die.

Since the 1990s, Connecticut and New York State have worked with EPA to implement a nitrogen pollution reduction plan – known as a Total Maximum Daily Load plan — to improve the Sound’s dissolved oxygen levels, and to protect aquatic animals and the environment. Through infrastructure investments of more than $2.5 billion to improve wastewater treatment, the total annual nitrogen load to Long Island Sound is now some 47 million pounds less than the yearly discharge in the early 1990s. Alongside this reduction, the area of hypoxia, based on a five-year rolling average, was 94 square miles in 2020, compared to the average from 1987-2000, before the plan went into effect, of 205 square miles.

The peer-reviewed study, published in January of this year in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, titled Reducing Hypoxia in an Urban Estuary Despite Climate Warming, documents increased levels of dissolved oxygen in Long Island Sound since 1994 in response to the nitrogen load reductions. This is the first peer-reviewed paper documenting these improving trends in Long Island Sound and is one of the few documented recoveries to a nutrient-caused hypoxic coastal system worldwide.

The paper’s authors, University of Connecticut scientists Michael Whitney and Penny Vlahos, also determined that the DO improvements occurred despite decreases in the solubility of DO due to warming waters. They emphasized that DO levels still fall below water quality standards during the summer and that projected warming will result in further declines.

EPA is continuing to work with Connecticut and New York to work on further reducing nitrogen pollution to improve water quality and to mitigate the future impact of climate change on hypoxic conditions.

The DO measurements used in the study come from samples collected and analyzed by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the Interstate Environmental Commission as part of a water quality monitoring program funded by the Long Island Sound Study. To see a chart with the year-by-year measurement of the hypoxic area of the Sound since 1987, visit https://longislandsoundstudy.net/ecosystem-target-indicators/lis-hypoxia/.

Long Island Sound is an estuary that provides economic and recreational benefits to millions of people while also providing habitat for more than 1,200 invertebrates, 170 species of fish and dozens of species of migratory birds.

The Long Island Sound Study, sponsored by the EPA and the states of Connecticut and New York, is a partnership of federal, state, and local agencies, universities, businesses, and environmental and community groups with a mission to restore and protect the Long Island Sound.

Visit https://www.longislandsoundstudy.net for more information.

# # #

Clams and oysters are an important source of seafood and support a vitally important aquaculture industry for Long Island Sound. But did you know that oyster and clam aquaculture also serves an important ecological role in improving water quality in the Sound?

The shellfish take up nutrients such as nitrogen when they filter feed on phytoplankton (commonly known as algae). By reducing excess algae in the Sound, they are also reducing the chance of algal blooms that can rob coastal waters of the oxygen fish and other animals need to breathe. Recently, the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s Milford Lab, working with partners including the NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science and Stony Brook University, set off to find out just how valuable shellfish are in improving water quality in the coastal waters of Greenwich, CT. In the study, recently published in Environmental Science & Technology, the researchers determined that it would cost between $2.8-$5.8 million a year in infrastructure improvements, such as wastewater treatment upgrades and stormwater best management practices, to remove the same amount of nitrogen as the “ecosystem services” provided by shellfish.

An article on the NOAA website describes how the researchers estimated the ecological and economic value of nitrogen reduction that results from oyster and clam aquaculture. It also describes how the researchers collaborated with local shellfish growers and the Greenwich Shellfish Commission to get the harvest data they needed for the study.

Three of the study’s authors serve on Long Island Sound Study committees: Gary Wikfors, chief of the Aquaculture Sustainability Branch at the Milford Lab, serves on the Management Committee; Julie Rose, a research ecologist at the Milford Lab, serves on the Science and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC), and Anthony Dvarskas, an economist at Stony Brook University, now with the New York State Attorney General’s Office, also serves on the STAC. The research is consistent with an Implementation Action of the Long Island Sound Study Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan to “conduct primary valuations of the critical ecosystem goods and services supported by Long Island Sound and its coastal habitats.”

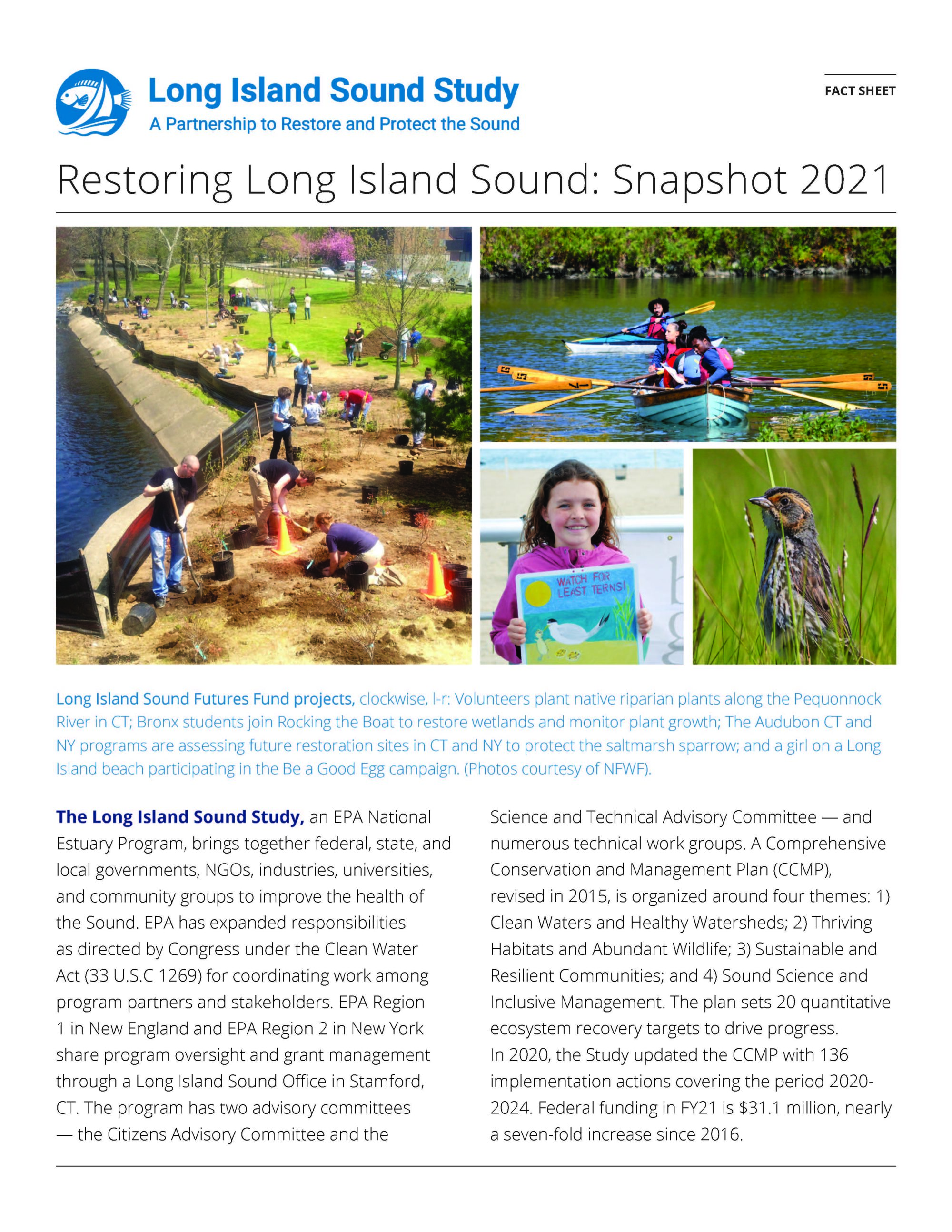

Restoring Long Island Sound: Snapshot 2021 is the latest fact sheet in our series highlighting different Long Island Sound Study initiatives. This fact sheet provides an overview of the program and work accomplished over the past year in order to achieve progress in accomplishing the goals established in the Long Island Sound Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan.

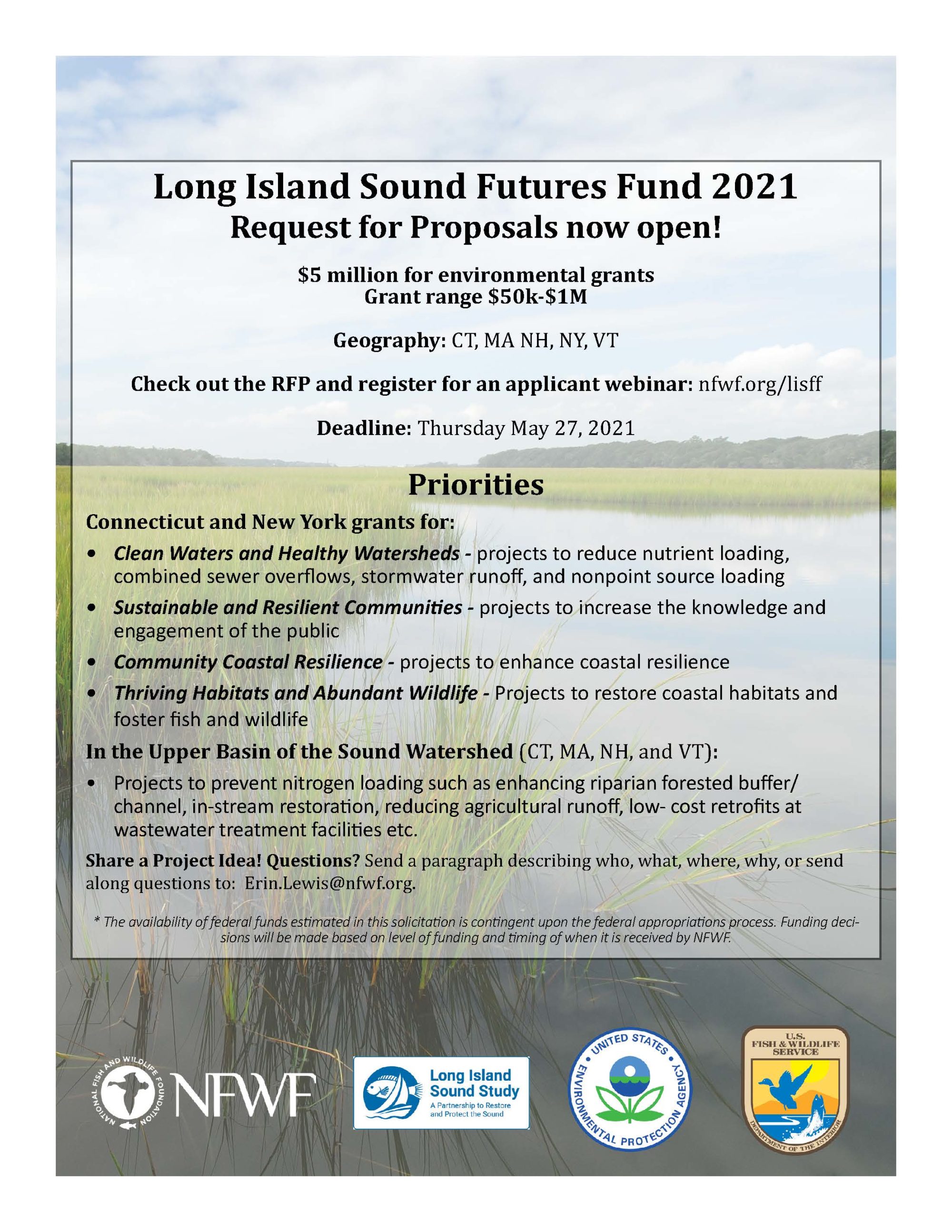

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation announced April 1 that it is seeking proposals for the 2021 Long Island Sound Futures Fund grant program. The Request for Proposals is available on the NFWF website.

In this grant cycle, there is potential funding of $5 million or more for grants to restore the health and living resources of Long Island Sound. The program is managed by NFWF in collaboration with the EPA, the Long Island Sound Study, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Healthy native ecosystems are constantly changing, but when a non-native species is introduced it can begin to wreak havoc. Non-native species are called “invasive” species when they out-compete native species living in our coastal habitats.

There are many ways aquatic invasive species (plants and animals) can be introduced from other parts of the world into the Sound, including from the ballast water held in the cargo holds of ships, accumulating on ship hulls (known as biofouling), from the packaging material of fish bait, from watercraft and rain gardens, from intentional release fishing bait release, escape from nurseries and water gardens, and intentional release of unwanted aquatic pets. This Sound Fact (published during National Invasive Species Awareness Week) focuses on two plant and one invertebrate species that are now calling the Sound home.

Devil’s Tongue Weed (Grateloupia Turuturu)

A red alga, or seaweed, this plant was discovered on Long Island Sound in 2004. Since it thrives in warm water, it has the potential to grow in abundance as the Sound’s water temperature increases. Grateloupia attaches to hard surfaces such as rocks and may compete with native red alga for important resources like space, light, and nutrients. One of the algae, Chondrus crispus, or Irish moss, serves as habitat for blue mussels and other invertebrates, as well as algal epiphytes (species that grow on the surface of other plants) that provide food for crustaceans. Want to learn more? CT Sea Grant has a factsheet on Grateloupia on its website. It has the ability to cover 100% of the habitat it invades, and it thrives in disturbed locations, on cobble, and around docks.

Sea Squirt (Didemnum vexillum)

This soft-bodied marine invertebrate grows on hard surfaces and feeds by filtering particles, such as phytoplankton and bacteria, from the water column. They are called sea squirts because large ones shoot water from their filtering siphons when they are picked up. They grow rapidly, including on docks, pilings, and the hulls of boats, and during outbreaks, they reach incredible densities, as many as hundreds per square foot. Besides compromising human structures sea squirts can out outcompete and suffocate filter-feeding bivalves such as mussels, scallops, and oysters. Want to know more? See the article by Dr. Stephan Bullard in the Summer 2012 issue of Sound Update, a special themed issue on invasive species.

Oyster Thief (Codium Fragile)

This green seaweed, also known as dead man’s fingers, or green fleece, was first discovered in the US in Long Island waters in the late 1950s. It can be seen year-round on open coasts, estuaries, tide pools, and intertidal and subtidal zones. It attaches to rocks, shells, or other hard substrates, and is often covered with epiphytic species. It is also found in sheltered habitats such as bays and harbors, and can outcompete native seaweed such as kelp and smother mussels and scallops, reduce the biomass of oysters, and lift the shellfish off the seafloor. It is not as abundant in the Sound as it was a decade ago.

What You Can Do

Want to help stop the spread of aquatic invaders? In the summer environmental organizations and agencies may sponsor volunteer invasive species removal events in local rivers and lakes. The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the New York State Department of Energy and Environmental Protection also have useful information on what you can do on their websites:

- Examples of Aquatic Invasive Species In Connecticut

- Aquatic Invasive Species in New York State – NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation

More information:

- Robert Burg, Long Island Sound Study, rburg@longislandsoundstudy.net, P: (203) 977-1546

- Paul C. Focazio, Communications Manager, NYSG, paul.focazio@stonybrook.edu, P: (631) 632-6910

- Judy Benson, Communications Coordinator, CTSG, judy.benson@uconn.edu, P: (860) 287-6426

Stony Brook, NY and Groton, CT (Feb. 16, 2021) –Eight research projects that will examine various facets of the water chemistry and habitat quality of Long Island Sound and potentially yield more effective management decisions have been awarded more than $2.8 million in federal funding through the Long Island Sound Study Research Grant Program.

The projects, supported by a partnership of the Sea Grant programs of Connecticut and New York (CTSG and NYSG, respectively,) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Long Island Sound Study (LISS), will attempt to answer questions critical to advancing restoration of the estuary and its watershed. All the awards are supplemented with matching funds of at least 50 percent of the grants, extending the value of the research package to more than $4.2 million.

All the projects will span two years, with work slated to begin this spring.

The eight research projects are the latest to be awarded through the Long Island Sound Study Research Grant Program, run by NYSG and CTSG since 2008. Including the new awards, the program has funded ecological research in more than 30 areas. It represents the largest research investment into the Sound, designated an estuary of national significance and one of the most valuable natural resources for both states.

The projects are:

- “Can Watershed Land Use Legacies Inform Nitrogen Management?” (University of Connecticut, Ashley Helton, Chester Arnold, Emily Wilson, David Bjerklie; University of New Hampshire, Wilfred Wollheim; CT DEEP, Mary Becker, Chris Bellucci; Footprints in the Water, Paul Stacey: $487,391). This project will examine the impact of historical land use practices in managing nitrogen.

- “Evaluating Thin Layer Placement in Long Island Sound Marshes Using a Multi-Scale Approach” (University of Connecticut, Beth Lawrence, Ashley Helton, Chris Elphick; CT DEEP, Min Huang: $470,969.) In this project, different types of sediment for effective marsh rebuilding will be assessed.

- “Can They Get Out? Assessing the Effects of Low Streamflow on Juvenile River Herring” (University of Connecticut, Eric Schultz, James Knighton, Cary Chadwick: $231,013.) Researchers in this project will identify barriers to the outmigration of juvenile alewife, a keystone species in the Sound’s food chain.

- “Establishing Robust Bioindicators of Microplastics in Long Island Sound: Implications for Reliable Estimates of Concentration, Distribution and Impacts” (University of Connecticut, J. Evan Ward and Sandra Shumway, $301,150.) One of two projects examining how different types of marine life can contribute to efforts to quantify and remove pollutants, this research will examine the use of slipper snails, tunicates and oysters as bioindicators of the concentrations and impacts of microplastics.

- “Quantifying the Ability of Seaweed Aquaculture in Long Island Sound to Remove Nitrogen, Combat Ocean Acidification, Improve Water Quality and Benefit Bivalves” (Stony Brook University, Christopher Gobler, Michael Doall; GreenWave, Kendall Barbery: $238,933.) In this project, the ability of cultured seaweed and shellfish to remove nitrogen, combat ocean acidification, improve water quality and benefit aquaculture will be measured.

- “Constraining Models of Metabolism and Ventilation of Bottom Water in Long Island Sound Using Oxygen Isotopes” (University of Connecticut, Craig Tobias, James O’Donnell: $694,386.) One of three projects focusing on conditions in water and sediment chemistry, this work will examine factors that influence recovery from hypoxia (low oxygen).

- “Improving Eelgrass Restoration Success by Manipulating the Sediment Iron Cycle” (University of Connecticut, Craig Tobias and Jamie Vaudrey; and Cornell Cooperative Extension, Chris Pickerell: $323,404.) This project will evaluate methods to overcome sediment conditions that may impede eelgrass recovery.

- “Alkalinity of Long Island Sound Embayments” (University of Connecticut, Penny Vlahos and Michael Whitney; Save the Sound, Peter Linderoth; CT DEEP, Katie O’Brien-Clayton: $131,088.) This research will evaluate the vulnerability of embayments to changes in acidity that can be harmful to shellfish and other marine life.

Descriptions of all the Long Island Sound Study research projects, since the first grant cycle in 2000, are available in the research section of the LISS website.

In Their Words: Long Island Sound Study Research Projects

“EPA has a longstanding commitment to restoring and protecting Long Island Sound, one of the country’s most important estuaries. This funding will advance ecological research and play a critical role in improving water quality and reducing pollution, providing lasting results for the wildlife and wetlands in the Sound for years to come.” — acting EPA New England Regional Administrator Deb Szaro

“More than 10 percent of Americans live within 50 miles of the Long Island Sound’s shores, where issues like nitrogen pollution threaten water quality, marine life and coastal resiliency. These projects reflect EPA’s longstanding commitment to developing solutions to protect and restore the Sound to healthy waters, benefitting surrounding communities environmentally, economically and recreationally.” — EPA Region 2 acting Regional Administrator Walter Mugan

“This research competition resulted in an interesting diversity of projects. These include novel approaches to understanding and managing Long Island Sound and reaching the goals of increased water quality that support productive ecosystems for the benefit of wildlife and humans. In my opinion, it is a very smart investment for long-term benefits.” — Connecticut Sea Grant Director Sylvain De Guise

“New York Sea Grant is pleased to continue our longstanding partnership with Connecticut Sea Grant and the EPA through the LISS competitive research program. The Long Island Sound is an essential and beloved natural asset to the citizens of NY and CT and supports critical environment and human ecosystem services. The eight diverse and innovative research initiatives that were awarded funding will provide critical knowledge needed to ensure the health of the Sound today and into the future.” — New York Sea Grant Director Rebecca Shuford

“This grant cycle represents the largest amount of funding ever competed and resulted in a very competitive and diverse group of projects. This research effort is even more significant because it is tightly linked to management applications so will go far to improve our understanding of the Sound and help managers in their work to restore and improve the Sound’s waters and biota.” — CTSG Research Coordinator Syma Ebbin

“This cohort of projects continues the successful long-term collaboration between CTSG, NYSG and EPA LISS that continues to expand the knowledge base that is invaluable to aiding the management of Long Island Sound. The results of this research effort will benefit the LIS environment and its communities.” — NYSG Research Coordinator Lane Smith

About the Long Island Sound Study:

Long Island Sound is one of the 28 nationally designated estuaries under the National Estuary Program (NEP), which was established by Congress in 1987 to improve the quality of Long Island Sound and other places where rivers meet the sea.

The Long Island Sound Study is a cooperative effort sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency and the states of Connecticut and New York to restore and protect the Sound and its ecosystems. The restoration work is guided by a Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan under four themes: Clean Waters and Healthy Watersheds; Thriving Habitats and Abundant Wildlife; Sustainable and Resilient Communities; and Sound Science and Management.

For more on what you can do to make a difference, click over to the “Get Involved” or “Stewardship” sections of the Long Island Sound Study’s Web site. News on the Long Island Sound Study can also be found in New York Sea Grant’s related archives.

If you would like to receive Long Island Sound Study’s newsletter, please visit their site’s homepage and sign up for the “e-news/print newsletter” under the “Stay Connected” box.

About Connecticut Sea Grant:

Connecticut Sea Grant (CTSG), located at the UConn Avery Point campus, is a state and federal partnership funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Connecticut. CTSG, which in 2019 celebrated its 30th anniversary as a Sea Grant College Program, works to achieve thriving coastal and marine ecosystems and communities by supporting local and national research, outreach and education programs. CTSG accomplishes this by providing objective, science-based information to encourage individuals and organizations to make informed decisions, communicating scientific findings in a practical manner helpful to diverse audiences, and helping others balance the use and conservation of coastal ecosystems. Ultimately CTSG’s activities increase the resilience of the coastal communities, economies and ecosystems.

The program has three foci: research, outreach, and education. Outreach efforts include the CTSG Extension Program, and its Communications Program. The program also has an administrative staff committed to promoting understanding of the Sea Grant mission.

For more, visit https://seagrant.uconn.edu

About New York Sea Grant:

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University and the State University of New York, is one of 34 university-based programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated research, education and extension services promoting coastal community economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based information to many coastal user groups – businesses and industries, federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers, educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, University at Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office in Newark. In the State’s marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook University, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative Extension’s NYC and Kingston locations. For more, visit: www.nyseagrant.org.