It’s 4.a.m. The alarm sounds. AWW-UU-GAAA. AWWW-UUU-GAAA. Pitch black. I rush quickly out of bed to shut off my annoying alarm before I wake my entire family. After a quick shower, I pull on multiple layers of warm clothes before heading out the door to drive to the dock to join my colleagues on board the Research Vessel John Dempsey for the monthly survey of water quality in Long Island Sound. I’ve got to be there by 6 AM. At least it’s not snowing this morning, the seas should be calm, and we’re heading east so we should have a great sunrise, even if the temperature is only 21ºF.

The state agency I work for, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP), has been conducting water quality monitoring in the Sound since 1991. The monitoring is year-round, even during the coldest parts of the winter, because winter conditions can lead to poor water quality in the summer (more on that later).

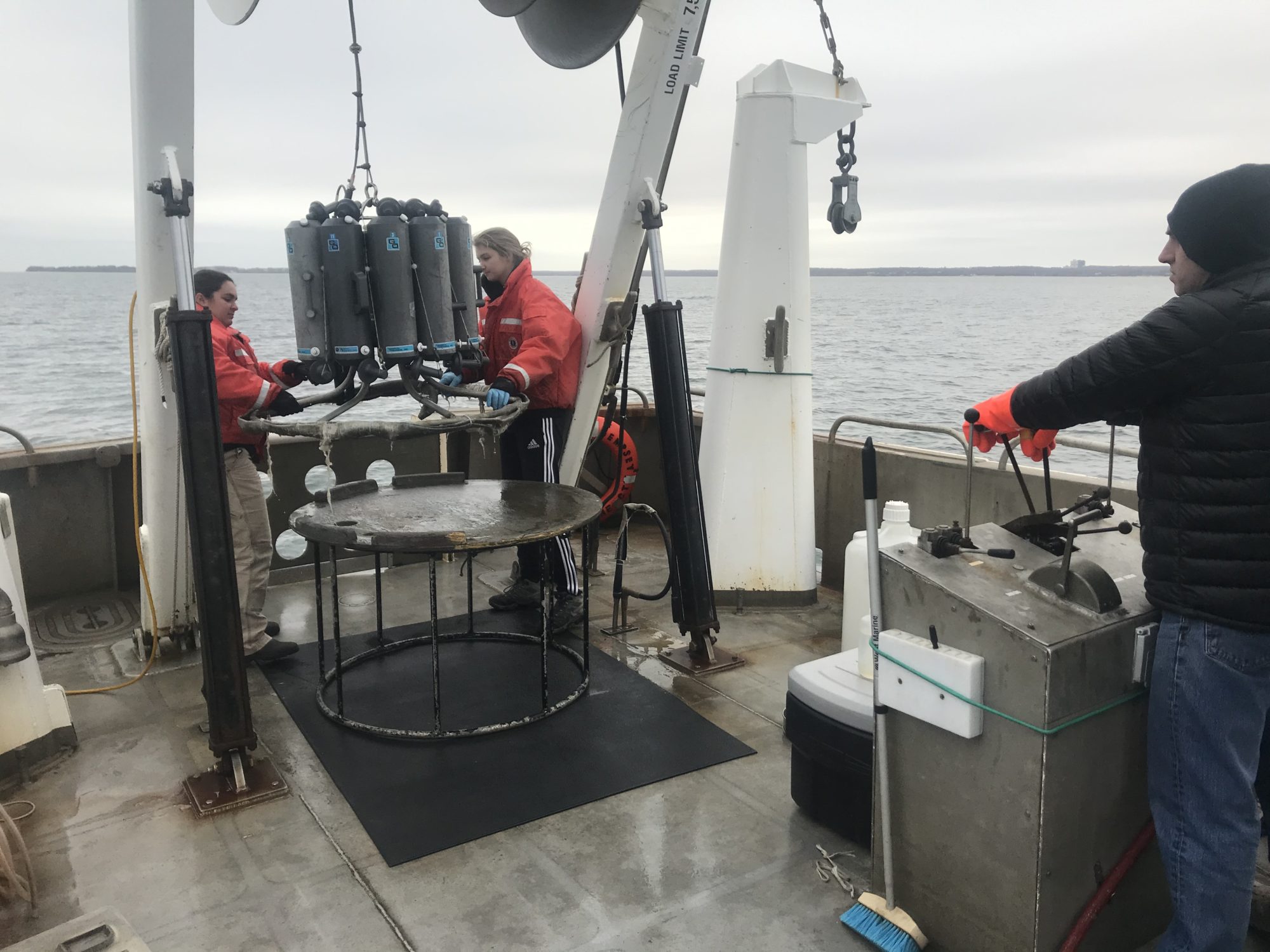

A typical survey takes us three days to complete; we take the ship to as many as seven locations per day, traveling as much as 15 miles between stations, to check on the health of Long Island Sound. We deploy heavy monitoring equipment called a rosette sampling array to the bottom depths of the Sound to collect water samples. As we sort out these samples in the onboard lab to prepare them to be analyzed later, the Captain steers the ship to the next station to make sure we keep on schedule. This is no cakewalk in the best of conditions, but just wait until you have to sample in the winter…. with below-freezing temperatures and an average 2.5-foot chop; with occasional 4-foot seas. Crew safety is of the utmost concern, especially around cold water.

While our fluorescent orange Coast Guard-approved float coats aren’t debuting on the New York fashion runways, they must be worn during deployment of any gear. We do not want to find ourselves in situations similar to Cold Water Boot Camp. Additionally, gloves, whether they are fishermen’s waterproof insulated gloves or nitrile gloves worn over stretch knits, are a must when deploying the rosette. Bare skin on cold, wet metal… no triple-dog dares aboard this research vessel.

It’s not so easy to deploy and retrieve our rosette sampling array which is used to collect water samples and houses our multi-parameter sonde (an instrument probe). The rosette sampling array is basically a 200-pound metal circle to which we attach 5-L Niskin sampling bottles. An electro-mechanical signal is sent through a cable to the trigger mechanism on the rosette, closing the bottles and collecting a sample. During winter surveys the trigger mechanism can freeze, when this happens we break out the heat gun and gently melt any ice that accumulated on the plastic pins.

Another challenge to sampling during the winter involves the sonde. While the sonde itself operates in water temperatures between -5 and 50ºC, it needs to be stored at temperatures above 0ºC. Being on the deck while transiting from station to station subjects it to temperatures and wind chills below zero; we’ve lost quite a few pH probes to freezing. So we bring it inside the cabin after every cast when the thermometer shows air temperatures below 0ºC.

Have you ever tried to pour water from one Snapple bottle into another while riding a roller coaster? I haven’t either, but it’s analogous to filtering water in rough seas. After we collect the water in the Niskins, we bring them into our shipboard laboratory where the water is filtered. The filtrate and filters are sent to the University of Connecticut for analyses.

So why do we sample in the winter anyway? We are concerned about hypoxia, which is when the Sound’s dissolved oxygen levels fall below 3 mg/L. Hypoxia is harmful to fish and other wildlife, and can even lead to fish kills. Fish that can scatter avoid the “dead zone” entirely. While hypoxia occurs in the summer, winter is a period in which some of the conditions that cause hypoxia, such as the growth of plankton blooms stimulated by excess nutrients such as nitrogen can occur. Our winter surveys are aimed at capturing the winter/spring plankton bloom as well as spikes in nutrient concentrations associated with the spring thaw that increases the amount of runoff from snow and ice melt into rivers and streams and eventually the Sound. The timing and magnitude of the bloom have implications for the severity and extent of hypoxic conditions seen over the summer.

It’s 4:30 PM. The sun is disappearing behind the clouds. As we finish up our day out on the Sound and enter Milford Harbor, I’m happy that we won’t have to break ice getting to the dock today and I long for the warm sunny days of summer sampling.

Katie O’Brien-Clayton is an Environmental Analyst with the CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Long Island Sound Monitoring Program. She has been with the program since 2006. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in Marine Science from Southampton College in 1999.

Information about the initial monitoring plan developed for Long Island Sound is available on the Long Island Sound Study website. Information about the CT DEEP LIS Sampling Program is available on our website at www.ct.gov/deep/liswaterquality.

A Really Cold Day Onboard the Dempsey

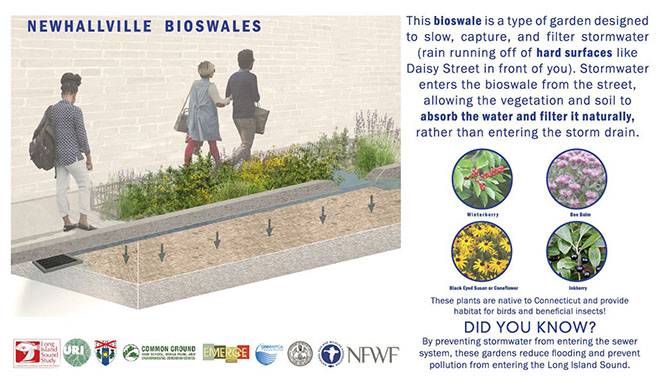

It looks like a flowerbed with attractive iron post fencing, but these 15- by 5-foot “bioswales” that are popping up on New Haven sidewalks are designed for more than trying to please the eye. These gardens include sidewalk curb cuts that change the flow of polluted stormwater rushing down a city street. Instead of heading downhill into a storm drain, stormwater gets diverted into the garden, and gets captured, filtered, and treated underneath in the soil. Since the final destination of stormwater is New Haven Harbor and the waters leading to Long Island Sound, installing bioswales throughout the City has the potential to make on an important contribution toward improving the health of the Sound.

How the Initiative Began

A GreenSkills job crew constructs a bioswale on Watson Street in New Haven. See more information in the photo gallery above.

Starting in 2014, the City of New Haven partnered with the Urban Resources Initiative (URI) and others to install and monitor bioswales as part of two different pilot projects. Staff from URI, a not-for-profit university partnership within Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies (Yale FES) went door to door and held community workshops in the Edgewood and Newhallville neighborhoods to explain the value of bioswales and seek support for their installation. Homeowners were encouraged to participate in the design process by helping to select plants and flowers. Through community engagement, URI received support to install 15 bioswales. URI used this opportunity to explore different bioswale designs and construction methods, working with crews from EMERGE Connecticut, a social service organization that trains formerly incarcerated individuals, to complete the physical installations. The non-profit group then followed a maintenance plan to ensure that the bioswales functioned as expected since trash and leaves can block the opening of the curb cuts. With help from researchers and students at Yale FES, bioswales were monitored to assess their effectiveness at reducing stormwater flow to the sewer and removing pollutants. These initial projects were made possible through a grant from the Long Island Sound Futures Fund.

Bioswales Expand into Downtown New Haven

The results of the Edgewood and Newhallville pilot projects impressed the City of New Haven, which received a federal grant to install up to 200 bioswales throughout the City’s downtown. The City’s downtown suffers from flooding during high intensity, short-duration rainfall events and bioswales are seen as a first measure to reduce runoff into the City’s storm sewer system. URI and EMERGE teamed up again to submit a bid for the construction of the first 100 bioswales. As the lowest bidder, the non-profit team won and recently completed the installation of this first wave of downtown bioswales. The team was also successful in winning the bid for the remainder of the bioswales to be built in the Downtown and Hill neighborhoods. While specific results depend on location and the severity of a storm, research from all the pilot and downtown projects has found that each bioswale can capture over 70 percent of stormwater from entering storm drains and treat more than 75,000 gallons a year.

What Pollutants are Being Treated?

When stormwater runs off the City’s impervious surfaces, it picks up pollutants such as nutrients, motor oil, pesticides, and bacteria along the way. Excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer and pet waste, trigger algal blooms in coastal waters. Animal plankton increase to eat the algae and when the algae and plankton die, bacteria start to break down the new organic material. The bacteria consume the oxygen in the water that fish and other animals need to survive, causing massive die-offs.

A Yale University graduate students enters a manhole on Watson Street to collect data from monitoring equipment installed in the storm sewer.

In addition, in some areas of the City, bioswales also help prevent another serious threat to the health of the Harbor and Long Island Sound: untreated sewage. In certain neighborhoods, such as Edgewood, there is only one underground pipe to convey the City’s stormwater and sanitary sewage. This is known as a Combined Sewer System. In dry weather, the pipes drain only sewage to the City’s Water Pollution Control Plant (WPCP) for treatment and discharge into the Harbor. But during a rain event, the volume of stormwater and sewage may exceed the plant’s treatment capacity. In that case, the untreated stormwater and sewage mix will be discharged directly into the Harbor untreated, which is referred to as a Combined Sewer Overflow or CSO. Combined Sewer Systems are common in large, older cities such as New Haven where infrastructure was installed over a hundred years ago (before treatment plants and the Clean Water Act). In New Haven, approximately 43 million gallons of untreated sewage and stormwater are discharged into the Harbor in a typical year. Constructing bioswales within combined sewer drainage areas helps to reduce this volume.

The Role of the LIS Futures Fund Grant Program

Since 2014, The Long Island Sound Futures Fund has awarded three grants to URI, providing nearly $275,000 in funding to initiate the two pilot projects and to provide ongoing support. The most recent grant, from 2017, is funding URI’s ongoing partnership with Yale FES to monitor the cumulative impact of multiple bioswales installed in the downtown sewershed. The monitoring is also providing data to assess the impact on reducing stormwater runoff, pollution and Combined Sewer Overflows.

This latest grant also helps URI and the City spread the word about bioswales. URI has held field trainings and informational tours for nonprofit staff and municipal officials in Bridgeport, Hartford, and Providence who want to observe the construction. The grant has also supported the design and installation of informational signage at a number of completed bioswales, serving to further inform people that visit, live and work in New Haven.

Investing in the Social Benefits of Green Infrastructure

While the bioswales provide important ecosystem benefits to urban areas, URI’s partnerships with other organizations have added social benefits. For example, by working with Common Ground High School students on the maintenance of bioswales, students not only improve the function of the installations but also received an education on the value of green infrastructure in treating stormwater pollution and improving coastal water quality. Additionally, URI also saw the potential to use the project as a job training program. By partnering with EMERGE Connecticut for bioswale installation, URI is providing training and paid jobs to formerly incarcerated residents of the City. EMERGE Connecticut’s mission is to help formerly incarcerated persons make a successful return to their families as responsible members and to their communities as law-abiding, contributing citizens.

Receiving the Prestigious Harvard Award

The Roy Family Award for Environmental Partnership at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government is presented every two years to an outstanding public-private partnership project that enhances environmental quality through the use of novel and creative approaches. in 2018, URI received this award along with its partners, the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, EMERGE Connecticut, the City of New Haven Department of Engineering, the Greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority, and Common Ground High School. The partners were praised for conducting “cutting-edge, scalable research for the advancement of green infrastructure and improvement of water quality in urban systems,” community engagement, and the green jobs training program. In a press release announcing the award, Henry Lee, director of the Environment and Natural Resources program at the Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, stated: “We believe that this partnership demonstrates the impact of a highly-local, adaptive, iterative approach in addressing a critical environmental and municipal capacity challenge – and one that can be replicated in cities and towns all over the world.”

URI has more information on each of the bioswale projects in the initiative, including the data on the monitoring results at its website.

Newhallville Pilot Project Slideshow Gallery

Downtown New Haven Slideshow Gallery

Could a hurricane make landfall and do serious harm to the Long Island Sound coast and the rest of New England? That was a question Peg Van Patten, Communications Director of Connecticut Sea Grant, raised in an article, “A Hurricane in New England?,” which she wrote for NOAA’s climate.gov website in 2010. The article describes the latest research at that time on predicting extreme weather events with a look back seven decades to when a really really big storm devastated Long Island Sound and the rest of the northeast–The Great New England Hurricane of 1938, also known as the Long Island Express. In that storm, around 600 people died (estimates vary) and damage in 2010 dollars was $5 billion.

Fishermen in Stonington, Connecticut, carry a wicker basket containing human remains found at the waterfront following the New England Hurricane of 1938. Photo by A. Morgan Stewart, The Day, courtesy of Peg Van Patten.

Of course, soon after Van Patten’s article was published, Long Island Sound was hit with Tropical Storm Irene, followed by Superstorm Sandy, two devastating storms that showed that not all hurricanes and tropical storms veer toward the oceans as they move up from the south.

Superstorm Sandy, a storm that transitioned from a hurricane to a post-tropical storm, was a particularly unusual event. Typically hybrid storms form in the ocean and become weaker. In this case, when Hurricane Sandy merged with an extratropical winter storm it made a left turn, veering west toward the east coast. It also got bigger and regained its strength, helping to make it one of the most costly and deadly storms in our history.

Most scientists agree that attributing specific extreme weather events such as Superstorm Sandy is challenging because these events by definition are rare. But as Van Patten pointed out in her article, many scientists believe that with a warmer climate, warmer, moister atmospheres over the oceans will result in stronger storms.

Predicting the frequency of extreme weather events is also difficult, but the northeast experience a hurricane making landfall about once a decade over the past hundred years, although few have had the impact as Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and the Great Hurricane of 1938.

Peg Van Patten’s article, “A Hurricane in New England?” is also an account of how her father’s family from Stonington, CT survived the 1938 storm. Van Patten included photographs from her father’s collection to highlight the storm’s impact.

The saltmarsh sparrow faces many threats to its survival. Development along the coast has replaced much of its tidal habitat. Contaminants and invasive species such as Phragmites degrade some of the habitat that is left. But the most critical threat, says Chris Elphick, an ornithologist and conservation biologist at the University of Connecticut, might now be the impact sea level rise has on the sparrow’s ability to reproduce.

Saltmarsh sparrows build their nests, lay their eggs and raise their young in the high marsh vegetation of tidal wetlands, close to the water’s edge. If they complete this whole process within 26 days, their young are likely to succeed before the extremely high tides of the month wash away the nests. But an increase of sea-level rise of even a couple of inches will likely mean more nests will wash away, and the species’ reproductive success will decline.

“We know that sea-level rise is going to keep on increasing for the next few decades, so with the rising sea level, the frequency with which nests are likely to flood is going to go up and that means the birds face a very uncertain future,” said Elphick, during a site visit to one of the prime Long Island Sound habitats for tidal marsh birds, the Barn Island Wildlife Management Area in Stonington, CT.

Elphick has been studying the saltmarsh sparrow, identified as Vulnerable BirdLife International, in Connecticut marshes for more than 10 years. Most of the sparrows breed in the northeast United States where a network of scientists, including Elphick, collaborate to monitor the health of tidal marsh birds and their habitat through the Saltmarsh Habitat and Avian Research Program. This group recently estimated the global population to be a little over 50,000 individuals.

In 2012, Elphick’s research was funded by the Long Island Sound Sentinel Monitoring for Climate Change Program. The Program sought to develop pilot “sentinel” indicators that would act as early warning signals to detect the impact of climate change in the Long Island Sound ecosystem. Sentinel indicators include species or habitats considered particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts in Long Island Sound.

Elphick and his co-investigator, Chris Field, at the time a PhD student at University of Connecticut, along with Min Huang of the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and colleagues from the University of Maine, were awarded a two-year grant that included monitoring the saltmarsh sparrow and three other tidal wetland birds at 141 marshland sites in Long Island Sound. Of the four birds studied, the saltmarsh sparrow is the most affected by high tides because they nest lower in saltmarsh vegetation.

“Saltmarsh sparrows are particularly sensitive to those flooding effects,” said Elphick. “They are like an early warning system. They are like the canary in the coal mine in that they tell us that things are changing.”

Elphick added, “They will be affected before everything else is affected, and so by studying this one species that most people have probably never heard of, we can learn something about the entire marsh system and how these marshes are going to fare in the future.”

Besides the tidal marsh birds, Elphick and Field studied other potential sentinels for the Sentinel Monitoring strategy, including beach-nesting birds, waterbirds that nest in coastal forests, and saltmarsh vegetation. Their findings are posted in the Climate Change and Sentinel Monitoring research projects section of the Long Island Sound Study website.

Watch a video of Chris Elphick discuss saltmarsh sparrows and climate change at the Barn Island Wildlife Management Area.

They look like strange objects from another planet. But the dome-shaped structures that were placed in the muddy waters off the Stratford Point shoreline offer more than a surreal view. They are helping to dissipate the energy from tidal waves. This artificial reef is being tested to see if it help to prevent erosion along the shore and give newly planted salt marsh vegetation a chance to grow.

While made of concrete, these “reef balls” are unlike concrete barriers such as seawalls because they are placed further out from shore, spaced apart and have holes. They allow the tidewater to come in—enough to provide suitable habitat for the plants and animals who live in the intertidal zone.

The salt marsh restoration is part of a project to restore a 40-acre parcel of tidal marsh, coastal bluff, dune, and coastal grassland habitats that had been severely degraded in the 20th century because of its use as a gun club. The reef ball installation is also being used as a model to demonstrate how “living shorelines projects” that provide erosion control, while restoring or enhancing natural shoreline habitats, can be used as an alternative to hard infrastructure projects in adapting to climate change.

The area where the salt marsh is being planted lost much of its sedimentation following a remediation project in 2001 to remove lead. Jennifer Mattei, a Sacred Heart University biologist and one of the managers of the Stratford Point project, said that her team tried the reef ball installation after earlier attempts to plant saltmarsh vegetation failed, and after Superstorm Sandy washed away a restored dune and 30,000 newly planted beach grass plants.

“Timing and the sequencing of habitat restoration is important for success,” said Mattei. “Having a reef in place first with the salt marsh behind it will dissipate wave energy and protect the dune. The reef will allow sediment to be deposited and build the shoreline.”

During storm events pressure sensors designed to measure wave energy were placed in front and behind the reef balls. The reef was found to have reduced wave energy by 30 percent, a significant help in not only preventing erosion, but in allowing for the accumulation of between one to six inches of sediment both behind and in front of the reef. For tidal areas, the ability to accumulate sedimentation is crucial in their ability to keep pace with sea level rise to prevent the salt marsh from becoming oversaturated and eroded.

If the restoration succeeds, the salt marsh will then not only provide critical wildlife habitat but will also play its role in reducing wave energy so that the project can move forward with dune and upper marsh restoration in areas that were damaged by Superstorm Sandy.

The Stratford Point site is owned by DuPont Corporation, which granted the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection a conservation easement, which will prevent the site from ever being developed and to use the site for environmental education. Audubon Connecticut has been designated as the caretaker for the site, while Sacred Heart University has partnered with Audubon and DuPont to restore the area. Sacred Heart has received funding through the Long Island Sound Futures Fund for the salt marsh restoration project and in 2015 for upland coastal restoration including a two acre pollinator meadow and the installment of trees and shrubs important for migratory birds. SHU is helping to develop the overall management plan for the site with Audubon.

Watch a video of Sacred Heart University students planting salt marsh vegetation (Spartina alterniflora) at Stratford Point.

Jennifer Mattei, a professor of Ecology and Evolution at Sacred Heart University, is also founder of Project Limulus, a citizen science project that enlists volunteers to monitor for horsehoe crab populations in Long Island Sound.

A privately-owned dam that once powered a paper mill was removed from the Jeremy River in Connecticut – and for the first time in over 300 years, migratory species of fish including Atlantic salmon, sea lamprey, and eastern brook trout are able to reach their historic spawning areas.

The 1.5-acre former mill property, including the dam, was sold to the Town of Colchester by a local family for a dollar. Since the building was already partially collapsed, the Town was awarded $860,000 in state grants to demolish the structure, clean up the site, and convert the area to a riverfront park. The dam removal, which took place in 2016, was led by The Nature Conservancy, in consultation with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. It received financial support from the US Fish and Wildlife Service and National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Long Island Sound Futures Fund, a grant program that receives technical and financial support from LISS.

Now that the dam has been demolished, 17 stream miles in the Jeremy River, Meadow Brook, and other tributaries have been reconnected to the Salmon and Connecticut Rivers – opening up nearly the entire watershed to the Sound. But there are still many more dams in existence that prevent the passage of fish from reaching their historic spawning areas, sometimes many miles upstream. It is estimated that there are between 4,000 and 5,000 dams in Connecticut alone, and the upper end of this range would translate to about one dam per square mile.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused devastation throughout much of the mid-Atlantic seaboard of the United States. Despite all of Hurricane Sandy’s negative impacts on our area there was one beneficial outcome to report. Hurricane Sandy’s storm surge helped to remove a manmade earthen berm at the mouth of Sunken Meadow Creek at Sunken Meadow State Park in Kings Park, NY. The berm, built in the 1950s during park infrastructure development, had essentially cut off tidal flow from the Long Island Sound to the creek resulting in poor water quality and habitat within the ecosystem. Hurricane Sandy’s breach of the berm restored tidal flow to the creek for the first time in over 60 years and created the possibility for tidal wetland restoration within the waterway.

Luckily, Save the Sound, NYS State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, NYS Deptartment of Environmental Conservation, The Nature Conservancy, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service were already working on designs in 2012 for breaching and restoring the creek. In 2014, the partners developed a restoration plan for the creek, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation awarded funding to Save the Sound to strengthen the park’s resiliency. The project included tidal wetland restoration, fish passage feasibility studies, an 18-acre parking lot green infrastructure retrofit, and education and outreach. To date, the project has restored four acres of tidal wetland habitat in the creek. Over 100 volunteers have assisted with the restoration work with further planting opportunities available in 2019.

In 2018, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report titled Long Island Sound Restoration: Improved Reporting and Cost Estimates Could Help Guide Future Efforts (GAO-18-140). The report examined: what is known about the progress made toward achieving the 1994 CCMP; how the Long Island Sound Study intends to measure and report on progress toward achieving the 2015 CCMP; and the estimated costs of restoration. To assist EPA in addressing GAO’s recommendations, EPA hired the Horsley Witten Group and FB Environmental to prepare a report offering suggestions to help LISS further address the GAO’s reporting and cost estimating recommendations. The Horsley Witten Report summarizes findings from an evaluation of the LISS’s current reporting framework through the lens of the GAO leading practices, research on reporting practices from other estuary programs, and a cost analysis to generate ecosystem target cost estimates.

The report is available to download as a pdf document.

CONTACTS:

Mike Smith, w/NFWF, 703-623-3834

John Senn, U.S. EPA Region 1, 617-918-1019, senn.john @epa.gov

Tayler Covington, U.S. EPA Region 2, 212-637-3662, covington.tayler@epa.gov

Bridgeport, CT (November 4, 2019) – Today, top federal and state environmental officials from New England and New York announced 35 grants totaling $2.6 million to state and local government and community groups to improve the health and ecosystem of Long Island Sound.

The activities funded through the Long Island Sound Futures Fund (LISFF) show how projects led by local groups and communities make a big difference in improving water quality and restoring habitat around the Long Island Sound watershed. This grant program combines funds from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF).

“EPA has a longstanding commitment to help protect and restore Long Island Sound, which provides numerous environmental benefits and economic and recreational opportunities,” said EPA New England Regional Administrator Dennis Deziel. “These grants will help reduce impacts on the Sound from sources like stormwater and marine debris, which are priority issues for our agency.”

“EPA and its federal, state and local partners share great enthusiasm in supporting New Yorkers’ active engagement and stewardship to protect the Long Island Sound,” said EPA Region 2 Regional Administrator Pete Lopez. “These projects provide real long-term results, including improving water quality, preventing pollution, protecting and restoring habitat, wildlife and wetlands, as well as educating the public.”

The LISFF 2019 grants will reach more than 200,000 residents through environmental education programs and conservation projects. Water quality improvement projects will treat 8.2 million gallons of storm water, collect 46,000 pounds of floating trash, install 23,000 square feet of green infrastructure, and prevent 17,000 pounds of nitrogen from entering Long Island Sound. The projects will plan to open 13.5 river miles and restore five acres of riparian habitat for fish and wildlife. The grants are matched by $3.8 million from the grantees themselves resulting in $6.4 million in funding for conservation projects around the Long Island Sound watershed in New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont.

“These significant federal grants totaling $900,000 go to 15 great organizations to preserve and improve our beloved Sound. The purposes are as varied and visible as the needs. The work will be tangible and real: install litter traps and trash skimmers, begin restoration of salt marshes, spur growth of fish and bird populations, and support environmental education,” said U.S. Senator Richard Blumenthal.

“This is great news for Connecticut. These federal grants will go a long way in our efforts to preserving and protecting Long Island Sound, which is central to our state’s economy. I’ll keep working to increase funding for Long Island Sound through my seat on the Appropriations Committee so more deserving projects like these get funded,” said U.S. Senator Chris Murphy.

“The Long Island Sound is deeply important to the economy and ecology of Fairfield County. Conservation of the Long Island Sound is paramount, and these grants will go a long way in protecting its beauty and health,” said U.S. Congressman Jim Himes (CT). “Our shared hope is that residents of Fairfield County will be able to enjoy it for generations to come.”

“One of the greatest environmental challenges facing our nation and its communities is the protection and restoration of highly productive estuaries,” said Jeff Trandahl, Executive Director and CEO of NFWF. “The funding awarded today represents the Foundation’s and U.S. EPA’s continuing commitment, as well as the commitment of the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal and state partners, to restoration efforts aimed at improving the overall health of Long Island Sound.”

The Long Island Sound Study initiated the LISFF in 2005 through EPA’s Long Island Sound Office and NFWF. To date, the LISFF has invested $22 million in 451 projects. The program has generated an additional $39 million in grantee match, for a total conservation impact of $62 million for regional and local projects. The projects have reconnected 176 miles of river for fish passage, restored 1,114 acres of critical fish and wildlife habitat and open space, treated 212 million gallons of stormwater pollution, and educated and engaged 4.9 million people in protection and restoration of the Sound.

“Healthy estuaries, rivers and wetlands fuel surrounding communities that rely on them,” said Wendi Weber, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service North Atlantic-Appalachian Regional Director. “We are pleased to support these efforts that inspire people to be stewards of the natural world and restore free-flowing rivers and resilient marshes. These are investments that will pay off in water quality, recreational opportunities, healthy wildlife populations, and public safety.”

“The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) has been pleased with the review of this year’s applications and impressed with the caliber and quality of the projects submitted,” said DEEP Commissioner Katie Dykes. “These projects represent grassroots, on the ground opportunities to improve water quality in the sound, restore tidal wetlands, improve public access and build resiliency to the communities surrounding this important natural resource.”

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Commissioner Basil Seggos said, “The 2019 Long Island Sound Futures Fund grant awards will support multiple projects that promote clean water and community engagement and education throughout the Long Island Sound watershed. By working together, we can protect this vital ecosystem for generations to come.”

Long Island Sound is an estuary that provides economic and recreational benefits to millions of people while also providing habitat for more than 1,200 invertebrates, 170 species of fish and dozens of species of migratory birds.

The grant projects contribute to a healthier Long Island Sound for everyone, from nearby area residents to those at the furthest reaches of the Sound. All 9 million people who live, work and play in the watershed impacting the Sound can benefit from and help build on the progress that has already been made.

About the National Fish and Wildlife FoundationChartered by Congress in 1984, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) protects and restores the nation’s fish, wildlife, plants and habitats. Working with federal, corporate and individual partners, NFWF has funded more than 4,500 organizations and generated a conservation impact of more than $5.3 billion. Learn more at www.nfwf.org.

About the Long Island Sound Study

The Long Island Sound Study, developed under the EPA’s National Estuary Program, is a cooperative effort between the EPA and the states of Connecticut and New York to protect and restore the Sound and its ecosystem. To learn more about the Long Island Sound Study, visit www.longislandsoundstudy.net.

LONG ISLAND SOUND FUTURES FUND 2019 PROJECTS

GRANTS IN CONNECTICUT

Green Infrastructure to Improve Water Quality and Coastal Resilience in Bridgeport (CT)

State of Connecticut, Department of Housing

Project Area: Seaside Park neighborhood, Bridgeport, Connecticut

Grant: $250,000

Grantee Matching Funds: $167,000

Total Conservation Impact: $417,000

The project will install green infrastructure in the Seaside Park neighborhood of Bridgeport, Connecticut. It will convey, infiltrate and filter stormwater from a pump station that is part of a coastal flood defense system; improve water quality in Bridgeport Harbor and Long Island Sound by reducing stormwater runoff; and address flooding in the South End of the City.

Green Infrastructure at Webster Street Parking Lot to Improve Water Quality in Norwalk Harbor (CT)

City of Norwalk

Project Location: Webster Street Parking Lot, City of Norwalk, Connecticut

Grant: $250,000

Grantee Matching Funds: $400,000

Total Conservation Impact: $650,000

The project will install green infrastructure as part of the repaving of a 5.4-acre public parking lot in the South Norwalk business district located near the Norwalk Harbor, which drains stormwater into Long Island Sound in Connecticut. It will alleviate local flooding, increase tree canopy and prevent 6,700,000 gallons of stormwater and 12 lbs. of nitrogen annually from flowing into the Sound.

New Strategies to Prevent Litter for a Trash Free Long Island Sound (CT)

Yale University

Project Area: Beaver Ponds Park, New Haven, Connecticut

Grant: $39,949.64

Grantee Matching Funds: $26,667

Total Conservation Impact: $66,616.64

The project will install three types of litter traps and analyze the type and amount of litter in the traps in New Haven, Connecticut. It will identify the best technology to trap litter and pinpoint sources of pollution from surrounding neighborhoods to inform management that better targets and prevents litter into New Haven Harbor and Long Island Sound.

Deploying a Skimmer in Stamford Harbor for a Trash Free Long Island Sound (CT)

SoundWaters

Project Area: Stamford Harbor, Stamford, Connecticut

Grant: $21,454.42

Grantee Matching Funds: $19,399.52

Total Conservation Impact: $40,853.94

The project will install a marine trash skimmer in Stamford Harbor, Stamford, Connecticut. It will remove 3,190 pounds of floatable marine debris annually from Long Island Sound.

Sliver by the River: Planning for Greening the Pequonnock River on the Bridgeport Waterfront (CT)

Trust for Public Land

Project Location: City of Bridgeport, Connecticut

Grant: $85,112.82

Grantee Matching Funds: $170,000

Total Conservation Impact: $255,112.22

The project will develop an alternatives analysis of the type of green infrastructure to add to the coastal hazard mitigation plan for a three-acre sliver of land along the Pequonnock River, Bridgeport, Connecticut. It will set the stage for improving water quality and enhancing community resilience to storms and floods in an urban coastal community of Long Island Sound.

Coastal Resiliency Action Strategy and Hazard Planning (CT)

The City of Groton

Project Area; City of Groton, Connecticut

Grant: $50,596.49

Grantee Matching Contribution: $33,730.99

Total Conservation Impact: $84,327.48

The project will identify tools for a strategic plan to address vulnerabilities and risks to coastal resilience in Groton, Connecticut. It will provide actions to improve the City’s response to future storms and sea level rise.

Engaging Student Citizen Scientists for Long Island Sound (CT)

Earthplace – The Nature Discovery Center, Inc.

Project Area: Westport and Norwalk, Fairfield County, Connecticut

Grant: $60,561

Grantee Matching Funds: $45,011

Total Conservation Impact: $105,572

The project will engage 56 student citizen scientists in five experiential learning programs about water quality and Long Island Sound ecology using rivers, harbors, and the Sound as outdoor classrooms, and make public presentations about the research at public events in Fairfield County, Connecticut. It will train students in conservation science and improve public knowledge and understanding of the Sound.

A “Sound” Long Island Sound Education and Field Studies Program for Urban Communities (CT)

Friends of Outer Island, Inc.

Project Area: Outer Island Unit, Stewart B. McKinney, U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service, National Wildlife Refuge, Branford and New Haven,

Connecticut

Grant: $5,000

Grantee Matching Funds: $3,885.63

Total Conservation Impact: $8,885.63

The project will deliver a ten-event experiential education series to immerse 385 students, teachers, families, and the public primarily from urban New Haven about environmental challenges faced by Long Island Sound in the footprint of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge island unit offshore of Branford, Connecticut. It will foster knowledge about Long Island Sound water quality, sustainability and coastal resilience among urban audiences.

Engaging Communities in “RiverSmart” Stormwater Management in the Pequabuck River Watershed (CT)

Farmington River Watershed Association

Project Area: The Pequabuck River Watershed of Long Island Sound, Bristol, Connecticut

Grant: $34,560

Grantee Matching Contribution: $29,172

Total Conservation Impact: $63,732

The project will conduct the RiverSmart education program connecting the story of local storm drains to the problem of stormwater pollution into local waterways that feed Long Island Sound. It will install green infrastructure in Bristol Connecticut and educate adults and youth groups about everyday actions people can take to reduce polluted stormwater from inland communities into the Sound.

Healthy Lawns, and Healthy Rivers for a Healthy Long Island Sound (CT)

Niantic River Watershed Committee, Inc.

Project Area: Niantic River Watershed of Long Island Sound, East Lyme and Waterford, Connecticut

Grant: $15,637

Grantee Matching Funds: $17,664

Total Conservation Impact: $33,301

The project will conduct a social marketing program for residents aiming to reduce or eliminate the use of fertilizer on lawns in the Niantic River watershed of Long Island Sound in East Lyme and Waterford, Connecticut. It will prevent 10,000 lbs. of nitrogen from fertilizer flowing into the Niantic River and ultimately Long Island Sound.

Long Island Sound – Stewards in Training (CT)

Sea Research Foundation, Inc.

Project Area: Schools in the following districts: Groton, New London,

New Haven, and Norwich, as well as programming in Stonington and

Groton, Connecticut

Grant: $9,654.92

Grantee Matching Funds: $8,935.69

Total Conservation Impact: $18,590.61

The project will provide 16 educational programs for middle and high school students and their teachers to expose them to Long Island Sound and STEM career resources, engaging them in hands-on scientific activities and mentorship from working professionals at Mystic Aquarium, Connecticut. It will open pathways for youth to achieve a better understanding of their connection with Long Island Sound and to green careers in the watershed.

Analyzing How to Increase Use of Reusable Bags to Reduce Plastic Pollution into the Sound (CT)

Citizens Campaign Fund for the Environment, Inc.

Project Area: Fairfield and New Haven County, Connecticut

Grant: $10,000.10

Grantee Matching Funds: $7,000

Total Conservation Impact: $17,000.10

The project will conduct an analysis in twelve towns to collect qualitative information about use of plastic, paper and reusable bags to determine the most effective ways to promote use of reusable bags in Fairfield and New Haven County, Connecticut. It will provide information about how to reduce the use of plastic bags among consumers and businesses to decrease one source of plastic entering Long Island Sound.

Bringing the Alewife Back to Alewife Cove (CT)

Connecticut Fund for the Environment/Save the Sound

Project Area: Fenger Brook, Alewife Cove, New London, Connecticut

Grant: $187,282

Grantee Matching Funds: $128,280

Total Conservation Impact: $315,562

The project will remove a barrier to fish passage, educating and engaging the community and students in project implementation and monitoring at Alewife Cove, New London, Connecticut. It will restore three miles of riverine migratory corridor benefiting alewife, sea lamprey and American eel that migrate between rivers and Long Island Sound.

Planning for Fish Passage on Beaver Brook (CT)

Town of Sprague

Project Area: Beaver Brook a tributary of the Shetucket River, Sprague, Connecticut

Grant: $48,900

Grantee Matching Funds: $48,499

Total Conservation Impact: $97,399

The project will develop engineered plans to remove barriers to fish passage on Beaver Brook, Sprague, Connecticut. The designs will address two barriers to fish migration at the mouth of the brook for alewife, blueback Herring, American eel, and sea lamprey along an important migratory riverine corridor of Long Island Sound.

Planning for Fish Passage at Papermill Pond Dam (CT)

Thames Valley Chapter of Trout Unlimited

Project Area: Papermill Pond Dam, Little River, Sprague, Connecticut

Grant: $53,500

Grantee Matching Funds: $63,280

Total Conservation Impact: $116,780

The project will conduct an engineering alternatives analysis, prepare designs, and commence pre-application consultations with federal and state agencies to advance installation of a fishway on the Papermill Pond dam, Sprague, Connecticut. It will set the stage for how to address a large barrier that has obstructed fish migration to Long Island Sound for over 150 years.

Planning for Fish Passage at the Dana Dam (CT)

Connecticut Fund for the Environment/Save the Sound

Project Area: Dana Dam, Merwin Meadows Park, Wilton, Connecticut

Grant: $75,000

Grantee Matching Fund: $75,000

Total Conservation Impact: $150,000

The project will develop plans to remove one barrier to fish passage on the Norwalk River, Wilton, Connecticut. It will set the stage to restore access to 6.5 miles of migratory riverine corridor for blueback herring, American shad, American eel and sea lamprey to Long Island Sound.

Planning for Fish Passage at the Highland Pond Dam (CT)

The Middlesex Land Trust, Inc.

Project Area: Sawmill Brook at tributary of the Mattabesset River, Middletown, Connecticut

Grant: $51,390

Grantee Matching Funds: $51,000

Total Conservation Impact: $102,390

The project will develop a design to remove one barrier to fish passage on the Sawmill Brook in Middletown, Connecticut. It will set the stage to restore access to one mile of spawning and nursery habitat along a migratory riverine corridor for alewife, blueback herring, American eel and sea lamprey to Long Island Sound.

Planning for Fish-Friendly and Flood Resilient Road-Stream Crossings in the Naugatuck Valley (CT)

Housatonic Valley Association, Inc.

Project Area: Naugatuck River Valley, Watertown, Beacon Falls and

Naugatuck in subwatersheds of Wooster Brook, Steele Brook, Fulling Mill

Brook, Beacon Hill Brook, and Hockanum Brook, Connecticut

Grant: $$67,097.56

Grantee Matching Funds: $45,750

Total Conservation Impact: $112,847.56

The project will create road stream-crossing management plans for three towns with historic runs of diadromous fish in the Naugatuck Valley, Connecticut. It will be officially adopted by each community as part of natural hazard mitigation planning and serve as a tool for securing support and financing for future road-stream crossing replacement projects.

Creating Thriving Habitats for the Shorebirds of Long Island Sound (CT)

Connecticut Audubon Society

Project Area: Long Island Sound Coastline of Connecticut

Grant: $75,000

Grantee Matching Contribution: $50,010

Total Conservation Impact: $125,010

The project will provide education and deliver targeted stewardship of American oystercatcher and other migratory shorebirds and habitat along the Long Island Sound coastline of Connecticut. It will increase public awareness about the value of sharing the shore with birds among recreational users and reduce disturbance to the birds’ breeding and roosting sites.

GRANTS IN BOTH CONNECTICUT AND NEW YORK

Coastal Habitat Restoration Planning for Salt Marsh & Nesting Birds in Long Island Sound (CT, NY)

National Audubon Society, Inc. (Audubon Connecticut and New York)

Project Area: Long Island Sound coastlines of Connecticut and New York

Grant: $50,497.85

Grantee Matching Contribution: $50,546

Total Conservation Impact: $101,043.85

The project will assess and identify priority high salt marsh restoration sites along the coast of Long Island Sound in Connecticut and New York. It will set the stage to restore salt marsh that buffers coastal communities from storms and provides habitat for nesting bird species such as salt marsh sparrow through effective coastal management planning.

Delivery of the Septic Improvement Program in Long Island Sound Watershed Communities (CT, NY)

The Nature Conservancy (New York and Connecticut)

Project Area: Long Island Sound Watershed of Suffolk County, and Nassau and Westchester Counties, New York and Connecticut

Grant: $175,000

Grantee Matching Fund: $118,562

Total Conservation Impact: $293,562

The project will support delivery of the Septic Improvement Program by engaging and assisting homeowners with all elements of the program to foster installation of modern on-site septic systems in Suffolk County; The project will share lessons learned with Nassau and Westchester Counties in New York and with one local government in Connecticut. It will expedite the installation of 40 advanced septic systems reducing nitrogen loads into Long Island Sound by 1,000 lbs. annually.

GRANTS IN NEW YORK

A Green New York City Playground for Public School 296Q and the Elmhurst Community (NY)

Trust for Public Land

Project Area: Public School 296Q, Elmhurst, Queens, New York

Grant: $191,755.39

Matching Funds from Grantee: $1,400,000

Total Conservation Impact: $1,591,755.39

The project will deploy green infrastructure on a school playground at Public School 296Q in Elmhurst, Queens, New York. It will enhance outdoor recreational green space and capture 1.5 million gallons of stormwater annually before it flows into Flushing Bay and Long Island Sound.

Developing a Management Plan for a Subwatershed of Long Island Sound in Westchester County (NY)

New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission

Project Area: Westchester County and Larchmont, Mamaroneck Town and

Village, New Rochelle, Pelham, and Pelham Manor in the subwatershed of

Pine, Stephenson and Burling Brooks and Larchmont Harbor

Grant: $100,000

Grantee Matching Funds: $67,000

Total Conservation Impact: $167,000

The project will update the Pine, Stephenson and Burling brooks and Larchmont Harbor sub-watershed management plan in Westchester County, New York. It will ensure that the causes and sources of nonpoint source pollution are identified, key stakeholders are involved in the planning, and restoration and protection strategies are identified that address local and Long Island Sound water quality problems.

Oyster Planting to Improve Water Quality in Long Island Sound (NY)

Town of Brookhaven

Project Area: Port Jefferson Harbor, New York

Grant: $92,473.56

Grantee Matching Funds: $102,000

Total Conservation Impact: $194,473.56

The project will plant 200,000 American oysters to assess their potential to remove nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon pollution from waters and repopulate a historic fishery in Port Jefferson Harbor, New York. Biofiltration by the oysters will remove 130 lbs. of nitrogen annually from a harbor of Long Island Sound.

Bioextraction of “Gold Coast” Kelp in the Oyster Bay Complex (NY)

Adelphi University

Project Area: Oyster Bay Complex: Town of Oyster Bay Marina, Laurel Hollow and West Harbor Beach, and Bayville, New York

Grant: $103,917.63

Grantee Matching Funds: $73,727

Total Conservation Impact: $177,644.73

The project will analyze growth of and the potential for bioextraction of pollution by sugar kelp in Long Island’s Gold Coast in the Oyster Bay Complex, New York. It aims to maximize the growth of kelp as a natural systems approach to bioextract pollution and enhance the marine environment in Long Island Sound and its harbors and embayments.

Hempstead Harbor 2020 Water Quality Monitoring Program-XII (NY)

The Incorporated Village of Sea Cliff/ Hempstead Harbor Protection Committee

Project Area: Outer and Inner Hempstead Harbor, Tappen Marina, and Glen Cove Creek, Nassau, County, New York

Grant: $75,000

Grantee Matching Funds: $58,572

Total Conservation Impact: $133,572

The project will conduct water quality monitoring in Hempstead Harbor, Nassau County, New York. It will inform management of Hempstead Harbor, an embayment of Long Island Sound.

Enhancing Community Education and Stewardship in Flushing Bay (NY)

Guardians of Flushing Bay

Project Area: Flushing Bay tidal embayment of Long Island Sound, Queens, New York

Grant: $48,250

Grantee Matching Fund: $41,425

Total Conservation Impact: $89,675

The project will construct a living dock and develop the Flushing Waterways Stewardship Kit in Flushing Bay and Creek, Queens, New York. It will engage environmental stewardship of Flushing Bay an urban tidal embayment of Long Island Sound.

Green Infrastructure and Coastal Resilience Planning in Long Island Sound Coastal Communities (NY)

Pace University

Project Area: Long Island Sound Coastal Communities, Westchester County, New York

Grant: $46,521

Grantee Matching Funds: $34,626.93

Total Conservation Impact: $80,877.93

The project will deliver a leadership education program for municipal officials focused on local land use planning to encourage the use of a combination of green infrastructure and coastal resilience practices in Westchester County, New York. It will integrate innovative planning that provides the co-benefit of improving local water quality and enhancing community resilience to storms, floods and sea level rise.

Sound Effects: A Public Conservation Education Program–II (NY)

The Whaling Museum Society, Inc.

Project Area: Cold Spring Harbor, New York

Grant: $9,864.94

Grantee Matching Funds: $5,050

Total Conservation Impact: $14,914.94

The project will design and host a public education series for 300 adults, families and elementary school students with hands-on learning and conservation activities in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. It will foster appreciation of Long Island Sound among a diverse range of people who will gain a stronger understanding of their impact on and need for stewardship of the Sound.

Long Island Sound’s Fresh Pond Festival (NY)

Salonga Wetland Advocates Network, Inc.

Project Area: Fresh Pond, Smithtown Bay, and Long Island Sound, Fort Salonga, New York

Grant: $5,700

Grantee Matching Funds: $3,800

Total Conservation Impact: $9,500

The project will conduct a festival and shoreline cleanup in Fort Salonga, New York. The event and hands-on cleanup will increase public awareness of and commitment to restoration and protection of the environment of Long Island Sound.

Students Working On-the-Water to Restore Tidal Wetlands along the Bronx River (NY)

Rocking the Boat

Project Area: Hunts Point Riverside Park, Story Avenue, Soundview and other sites in the Lower Bronx River, Bronx, New York

Grant Funds: $37,274.41

Grantee Matching Funds: $35,318.83

Total Conservation Impact: $72,593.24

The project will engage students to enhance nearby tidal wetlands including activities on the water in wooden boats constructed by them at the Rocking the Boat facility. It will educate community members of all ages about the ecological value of this natural habitat to the Bronx River and Long Island Sound in Hunts Point, New York and help develop an awareness of natural resources along a highly urbanized river and foster a community of local environmental stewards.

Restoring Native Plants to the Bronx River (NY)

Bronx River Alliance

Project Area: Bronx Park, Shoelace Park, Soundview Park, Muskrat Cove Lower Bronx River, New York

Grant Funds: $76,725

Grantee Matching Fund: $76,725

Total Conservation Impact: $153,450

The project will address the challenge of invasive plants and replant native plants, engaging volunteers from a newly created Riparian Invasive Plant Patrol (RIP) along the shoreline of the lower Bronx River, Bronx, New York. It will restore healthy, functioning riparian habitat along a river that feeds Long Island Sound.

GRANTS IN MASSACHUSETTS

Upgrading the South Hadley Wastewater Treatment Plant Decreasing Nitrogen into Long Island Sound (MA)

Town of South Hadley

Project Area: South Hadley Wastewater Treatment Facility, Chicopee, Massachusetts

Grant: $132,600

Grantee Matching Funds: $88,400

Total Conservation Impact: $221,000

The project will upgrade sensors and systems at the wastewater treatment plant in Chicopee, Massachusetts. The equipment and system enhancements will provide the most up-to-date and accurate monitoring and management of dissolved oxygen and nitrogen levels at the plant and decrease nitrogen discharge to Long Island Sound.

GRANTS IN VERMONT

Deploying a Nutrient Reclamation Project in the Long Island Sound Watershed-II (VT)

The Rich Earth Institute

Project Area: Windham County and adjacent counties in the Upper Basin

of the Connecticut River, Long Island Sound Watershed, Vermont

Grant: $80,000

Grantee Matching Funds: $184,750

Total Conservation Impact: $264,750

The project will deploy innovative nutrient reclamation technology in Windham County and adjacent counties in Vermont. It will divert 1,050 lbs. of nitrogen annually from entering the Connecticut River and ultimately Long Island Sound.

Advancing Deployment of the Nutrient Reclamation Project in the Long Island Sound Watershed-II (VT)

The Rich Earth Institute

Project Area: Windham County, Upper Basin of the Connecticut River, Long Island Sound Watershed, Vermont

Grant: $43,890

Grantee Matching Funds: $31,250

Total Conservation Impact: $75,140

The project will identify new sites to install innovative nutrient reclamation and recycling technology in Windham County, Vermont. The planning will expand the number of sites committing to install a technology designed to reduce nitrogen entering the Connecticut River and ultimately Long Island Sound.

The spring 2019 issue of Sound Update focuses on Long Island Sound Study’s Year in Review of 2018. Various clean water, habitat restoration, education, and science projects from Connecticut and New York are highlighted. Download Sound Update.