By: Maya Ray, 2024 Long Island Sound Study Intern

Shellfish are a staple part of Long Island Sound’s culture, playing a key role in recreational fishing, resident livelihoods, and are a star attraction of many beloved restaurants along the Sound’s coast. With the help of the Collective Oyster Recycling and Restoration (CORR), a recently launched non-profit, inventive efforts to recycle and restore shellfish are underway, allowing diners to help restore shell beds one five-gallon bucket at a time.

Oysters rely on the shells of their companions for reproduction. The “babies”, called spats, require hard surfaces to grow on. While they can grow on rocks, ceramics, and other solid materials, their favorite place to mature is on the old shells of other oysters, due to the added protection from predators. When more shells are available for them to latch on to, the survivability of the young oysters increases. With support from a $99,880 Long Island Sound Community Impact Fund grant, CORR is working with local restaurants to increase oyster populations along the shore.

Co-founders Tim Macklin, Todd Koehnke, and Eric Victor stay hands-on through every step of the shell recycling process.

“It’s a lot of time commitment, but we but we love it, said Koehnke. “We wouldn’t have picked anything else to do.”

Over 500,000 pounds of oysters have been recycled since CORR’s start in 2023. With hopes to recycle an additional 300,000 pounds next year, this massive restoration effort to bring shell beds back to the Sound is just getting started.

Increasing the area of shell beds in Long Island Sound is also important for crustaceans, small invertebrates, and fish populations, which use the beds as hunting grounds or shelter. Increased oyster populations also help keep the Sound’s waters cleaner, filtering out algae, as well as excess nutrients in the water, such as nitrogen from inland runoff. A single mature oyster can filter around 50 gallons of water a day. With the help of oyster recycling programs, waters all along the coast can have better water quality and more biodiversity.

“So overall, the more oysters you have in Long Island Sound, it’s just going to benefit it, and help keep it a healthy and clean environment,” said Macklin.

Recycled shells are being supplied by restaurants across the state. When people dine, they are encouraged to place used oyster shells in CORR buckets that line tables. Eateries then collect the oyster shell waste and prepare it in five-gallon buckets for transport to the recycling facility. CORR vehicles pick up the shells and take them to the recycling facility, where they are thoroughly cleaned and left to cure and sanitize for six months. While in the curing process, they are decontaminated by the sun and weather, while insects and wildlife remove any leftover residue. This ensures that the shells are bacteria-free and safe to reintroduce to the Sound.

“And the neat thing is, we step back with the pile [of shells] and we’re like, humans ate all of those, every one of these touched someone’s plate,” said Koehnke.

By tabling at events, and even hosting oyster festivals, CORR is hoping to draw attention to the importance of shellfish recycling. The non-profit also partners with the Sound School in New Haven, helping them with a living shoreline project using reef balls by lending them cured shells.

CORR members are also part of the Fairfield Shellfish Commission and the Mill River Wetlands Committee. Involvement in these groups has improved outreach efforts across the state and created more opportunities for connecting with key groups, including students. As more and more people learn about and engage in oyster recycling, CORR plans to incorporate educational programming into its work.

“Everybody loves to get their hands dirty and actually see things,” said Macklin. “It’s one thing to talk about stuff, but when you can actually physically see it, I think it engages people a lot more.”

In addition to creating education and engagement opportunities, the success of the project has CORR looking to collaborate with more restaurants, expanding into more counties in Connecticut. They have already established themselves in nine counties spanning from Greenwich to Guilford. They also partner with Southington and Hartford in central Connecticut. Future efforts will expand eastward toward Stonington.

“We need to prove our record here on the big stage, so we’re hoping that just comes in time,” said Macklin.

Multi-Year Pilot Study on Long Island Explores Use of Sugar Kelp as Fertilizer Amendment

From late winter to early spring, cold waters in Long Island Sound create the perfect environment for long dark-brown and green lasagna-shaped seaweed strands to thrive. Attached to a rocky seabed or flowing from a stretch of rope suspended between buoys is sugar kelp, Saccharina Latissima. Its ribbon-like strands can grow as long as twenty feet or more providing habitat for juvenile fish and small invertebrates.

In addition to being used as a sweetener and thickening agent in commercial products and a popular ingredient in restaurants and home kitchens, sugar kelp can supplement traditional nitrogen-based fertilizers while providing water quality improvements.

“Long Island Sound is impacted by nutrient pollution, namely nitrogen pollution,” said Kimarie Yap, the Long Island Sound Study’s Bioextraction Coordinator. “This causes water quality issues, such as algal blooms, the depletion of oxygen in the water that marine animals need to breathe (known as hypoxia), and large-scale fish die-offs.”

As it grows, kelp absorbs excess nitrogen and other nutrients in the water column, acting as a filter and preventing algae from using the nitrogen, which can result in harmful blooms. Nutrients are absorbed into the seaweed’s tissue, making sugar kelp a natural source of micronutrients which are important for the yield, quality, and flavor of agricultural crops. Seaweed aquaculture of farmed kelp can support bioextraction in the Sound—the process of growing and harvesting shellfish and seaweed species in order to remove extra nutrients from coastal waters. Previous work in the western and central Long Island Sound has estimated that sugar kelp can remove between 38–180 kg 1 of nitrogen per hectare in a growing season.

Part of the Long Island Sound Study (LISS) Bioextraction Initiative is a Sugar Kelp Fertilizer Pilot Study, which launched in the spring of 2020. Researchers and agriculture specialists are setting out to determine if sugar kelp can be grown, harvested, processed, and successfully used on Long Island to support water quality and agricultural growers.

“On Long Island, we have sandy soils,” said Sandra Menasha, Vegetable/Potato Specialist with Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County. “Because of that, our soil does not hold onto the micronutrients that a plant needs very well because sand is all negatively charged, and so are a lot of our nutrients. Sugar kelp is known to be full of a lot of micronutrients. So, it can kind of replenish the soil.”

“This is where bioextraction’s strength comes into play, said Yap in a recent article about the pilot published in the Long Island Nitrogen Action Plan newsletter. “It is a management strategy currently available that can remove existing nitrogen after it has entered Long Island’s embayments.”

First-phase trials using sugar kelp fertilizer amendment were conducted in greenhouses at the Long Island Horticulture Research and Extension Center in Riverhead, New York. Two trials were conducted on tomato seedlings and tomato and petunia plants.

“[Working in the extension center] allows us to do more closely watched, smaller plot replicated studies to get a sense about what treatments work, what doesn’t work,” said Nora Catlin, PhD, Agriculture Program Director and Floriculture Specialist and Menasha’s collaborator on the pilot. “Then we bring them on to the farm and try them out with a grower and do it on a bit of a larger scale. My interest was primarily in seeing if this sugar kelp, compared to other similar amendments on the market, could fit in that same space of how those are used.”

“If seaweed, such as sugar kelp, could be grown locally and used as fertilizer to impart the nutrients naturally taken up by the seaweed onto lawns and gardens, this could potentially help close that nutrient loop and would be a better, more sustainable option for both marine and agricultural industries compared to importing kelp fertilizer, and thus excess nutrients, from other states,” said Yap.

Sugar kelp in the first round of greenhouse trials was grown in Riverhead on the north shore of Long Island. Subsequent trials used kelp cultivated on mooring lines in the East River, located in the Bronx, New York. First rinsed thoroughly with fresh water and line dried, the kelp was then cut, crushed into small pieces, dried in an oven and ground into a course meal. In addition to the meal, an extract was made from boiling dried kelp with water. However, later iterations of the study have not included rinsing the seaweed as researchers found little affects in salt concentrations between rinsed and unrinsed samples.

“After hearing from other researchers, we tweaked that formula because we heard from other folks that they weren’t finding a lot of differences between their rinsed and unrinsed kelp,” Catlin said. “For the sake of time and thinking about if someone were to do this step as a grower, we took that into account.”

In June of 2020, field trials on tomato plants showed no significant difference between plants with or without the fertilizer amendment. In addition to observational data, soil samples were taken and evaluated for nutrient levels, pH, soil electrical conductivity (the ability of soil water to carry an electric current), and organic matter. Fruits were harvested and sent off for nutrient and sugar analysis, and data was collected on yield and quality.

“For field production, tomatoes are the king of most farms,” explained Menasha. “Most farmers are willing to spend more on amendments to increase production and quality of tomatoes, whereas something like radishes have a small profit margin…your benefits aren’t going to be as realized.”

Research thus far has shown some mixed but promising results. Fruit analysis testing showed higher sulfur levels in kelp amended plots compared to plots that did not receive any kelp amendments. Research from Rutger’s University finds that sulfur applications to some crops, including tomatoes, can enhance their quality and flavor.

“When we analyzed the tomato fruit from this trial, where we had sugar kelp, we had higher levels of sulfur in the fruit,” said Menasha. “So, I can infer based on the research from Rutgers that there is likely a better taste in that tomato. Taste and quality are what keeps people coming back, so that’s a huge impact.”

CCE’s specialists were not, however, able to measure many of the reported benefits that people believe kelp can offer. But comparable results were generated between the pilot’s fertilizer amendment and commercially available kelp fertilizers, a good sign that future fertilizer supplements could be produced from Long Island Sound grown kelp and used by local growers, bypassing the need to introduce kelp fertilizers (and thus nutrients) from outside the region.

Moving into the next phases of the study, Catlin plans to explore the utility of different amendment products.

“I definitely want farmer input to see what form they wanted to use,” said Catlin. “Do you want to use kelp extraction? Do you want kelp meal? The farmer I worked with felt the meal would work better for his production system. But broadly, you want to engage grower input.”

Caitlin and Menasha also plan to explore how tomato plants could react to double treatment: grown with the kelp fertilizer amendment in greenhouses and treated with the amendment at field planting.

This pilot is funded by the Long Island Sound Study. $54,643 was awarded to Cornell Cooperative Extension for the most recent phase of trials.

- Kim, Jang & Kraemer, George & Yarish, Charles. (2015). Use of sugar kelp aquaculture in Long Island Sound and the Bronx River Estuary for nutrient extraction. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 531. 155-166. 10.3354/meps11331. ↩︎

Water Quality Conditions in Long Island Sound Continue to Improve

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Anya Grondalski, Science Communicator

agrondalski@longislandsoundstudy.net

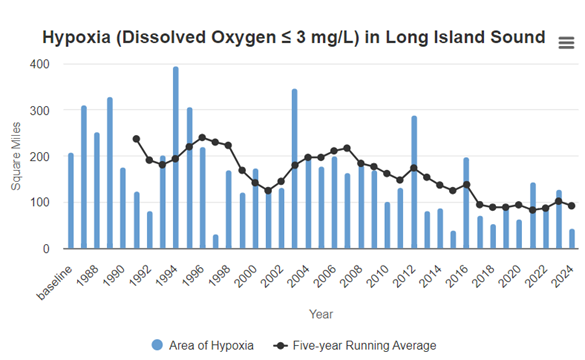

[STAMFORD, CT] — Scientists from the Long Island Sound Study (LISS) report the third smallest area of hypoxia—zones with low dissolved oxygen—since monitoring began in 1987. During the 2024 summer hypoxia monitoring season, the affected area measured 43.4 square miles, roughly the size of the Bronx, one of New York City’s five boroughs.

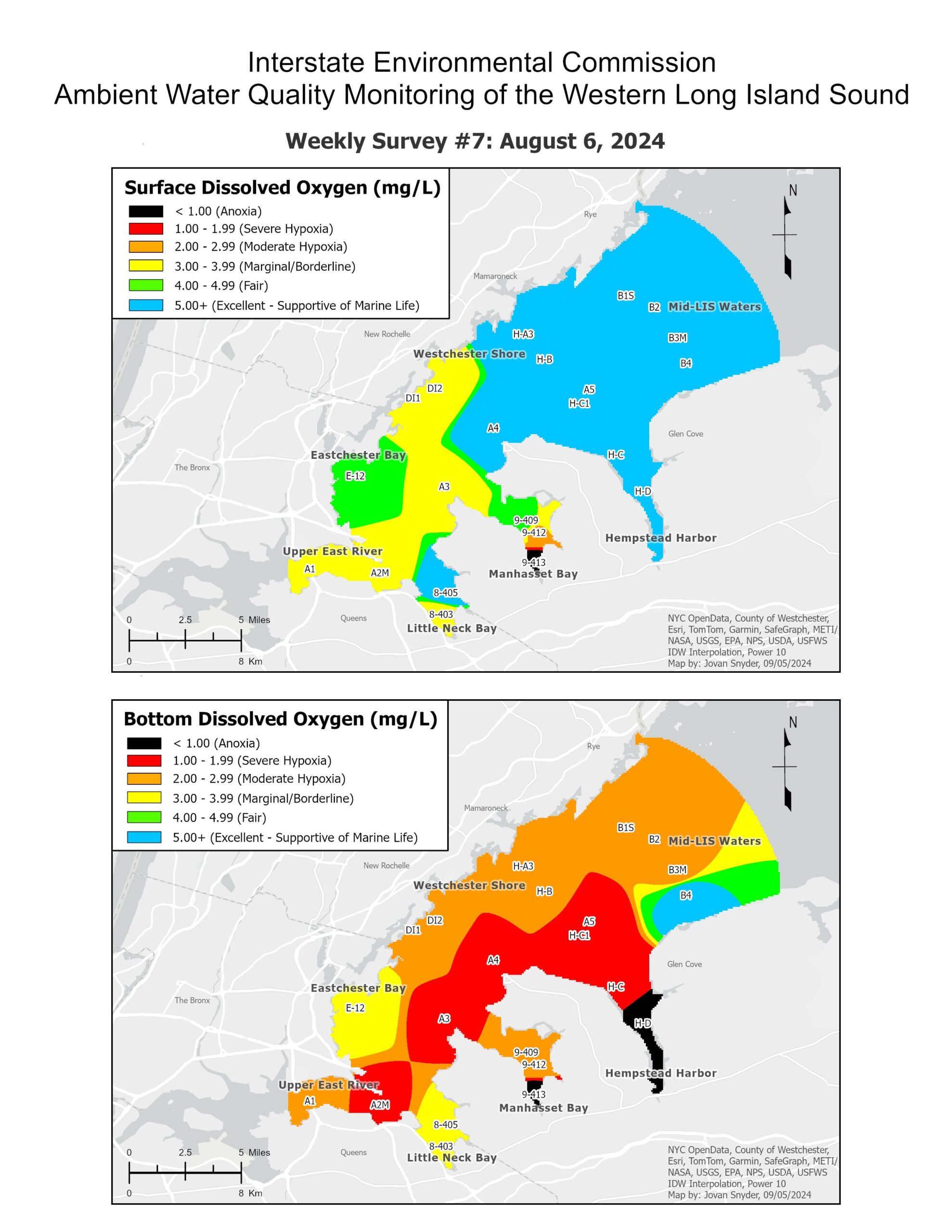

The duration of hypoxia measured 38 days, a decrease from 42 days reported for the summer of 2023. The minimum dissolved oxygen level observed during Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) open-water cruises reached 2.25 mg/L. In Long Island Sound, levels below 3 mg/L of oxygen have been considered the threshold for measuring hypoxic area. The minimum dissolved oxygen concentration observed during Interstate Environmental Commission (IEC) western Sound cruises was 0.76 mg/L in Manhasset Bay, New York, observed on August 6. Oxygen levels less than 1 mg/L are considered severely hypoxic and under these conditions, most marine life cannot survive even for short periods. Low levels of dissolved oxygen sometimes occur in bays due to reduced water circulation and high nutrient loads from runoff and wastewater, both associated with urban and suburban development.

The small area of hypoxia this summer has been attributed to weather conditions.

“Most of the summer through August was hot and wet, and repeated wind events mixed oxygen to deep waters which limited the area of hypoxia,” said Jim Ammerman, PhD, the Long Island Sound Study’s Science Coordinator.

Hypoxic areas, commonly referred to as dead zones, are places where water does not have enough dissolved oxygen to support aquatic life and are usually caused by nutrient pollution. Excess nitrogen, a nutrient that promotes algae growth, is a major contributor to hypoxia. When algae, fueled by these excess nutrients, die and bacteria decompose, any oxygen left in the water is used up. Excess nutrients can also increase the occurrence and severity of harmful algal blooms that can be toxic to humans and animals. A lack of oxygen in the water can lead mobile animals, like fish and crabs, to leave the area in search of healthier water. But species that can’t escape, like shellfish and worms, are either harmed significantly or die from suffocation.

Hypoxia can impact coastal waters, rivers, streams, lakes and estuaries like Long Island Sound, and happens most often in the summer when waters are naturally layered, or stratified, due to higher temperatures. Heat from the sun warms the top layer of the Sound, which floats on denser, cooler and saltier water beneath. When water stratifies, mixing of oxygen from the surface to bottom waters is less frequent. Hypoxia usually ends in September when temperatures cool and weather events, such as increased wind, mix water layers and redistribute nutrients and oxygen.

“Physical conditions in the estuary’s waters, such as stratification, create the potential for oxygen to decrease in deeper waters,” said Jim Hagy, PhD, an expert on coastal hypoxia with the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Research and Development. “However, hypoxia is primarily caused by excess nutrients, which increases the amount of organic matter that eventually sinks and decomposes, consuming oxygen faster than it can be replaced.”

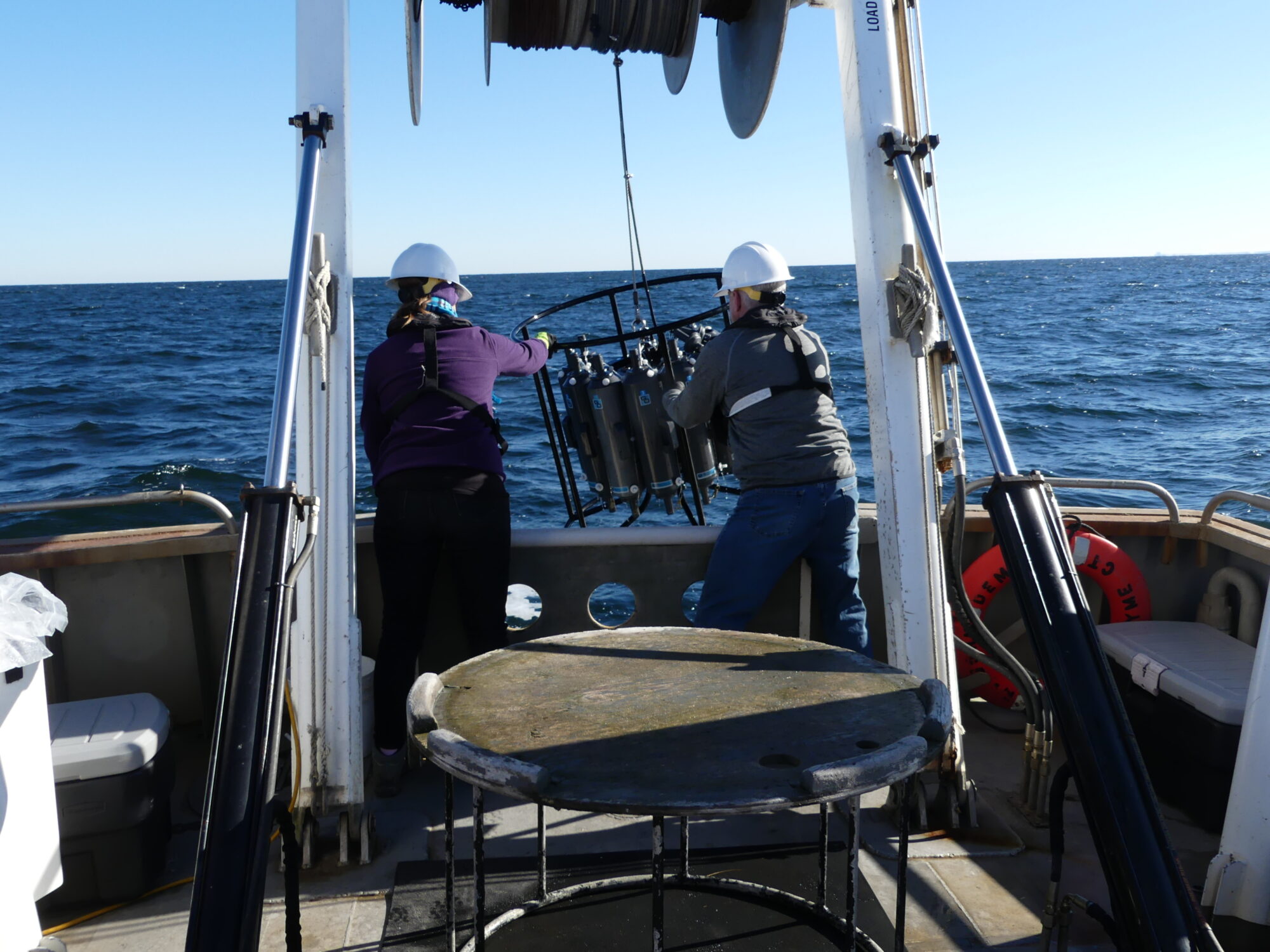

Environmental analysts with CT DEEP lead annual water quality monitoring in the Sound through the Long island Sound Water Quality Monitoring program, which is funded by LISS. Dissolved oxygen levels are measured at multiple stations across the estuary bi-weekly from June-September aboard the research vessel John Dempsey. You can find annual WQMP reports here.

Hypoxia is measured in the western Long Island Sound by the Interstate Environmental Commission (IEC), which monitors 22 stations weekly during the summer.

How Hypoxia is Being Reduced

LISS tracks both the extent (size) and duration (number of days) of hypoxia during summer months. Reducing hypoxia in Long Island Sound is a key priority for LISS and its partners. To address this issue, a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) agreement was established in 2000 between the EPA and the states of New York and Connecticut to limit nitrogen inputs into the Sound. LISS met its TMDL goal in 2016 and has continued efforts to reduce nitrogen loads by investing in wastewater treatment plant upgrades and addressing non-point source pollution from septic systems, stormwater, and agricultural runoff.

A 2021 research article by University of Connecticut scientists Michael Whitney and Penny Vlahos titled Reducing Hypoxia in an Urban Estuary Despite Climate Warming showed that decreasing trends in the size and volume of dead zones in the Sound coincide with reduced nitrogen loads. Water quality improvements have kept roughly 50 million pounds of nitrogen from polluting the Sound each year.

Predicting Dead Zones

In 2022, EPA Region 2, in collaboration with the EPA’s Office of Research and Development, launched the development of a Long Island Sound Hypoxia Forecast Tool, designed to predict the extent and duration of hypoxia in the Sound and its bays each summer. The tool, set to be released in spring 2025, will combine the work of scientists, researchers and communicators and will act as an engagement opportunity, increasing public awareness of hypoxia and its impact on water quality, habitat and wildlife. Stay tuned for more information about the tool’s release at longislandsoundstudy.net.

“Through consistent investments in research and environmental monitoring, the Long Island Sound science and management community has learned a great deal about hypoxia in Long Island Sound,” said Hagy. “The Long Island Sound Hypoxia Forecast will provide an opportunity to share and highlight that understanding with the public, thus increasing awareness of hypoxia and other nutrient-related issues in the Sound. While substantial progress has been made in reducing hypoxia in recent decades, there’s more work to do.”

The summer 2023 issue of Sound Update focuses on Long Island Sound Study’s Year in Review of 2022. It includes information on the latest round of Long Island Sound Futures Fund projects, and stories on some of the work advanced in 2022, including the expansion of the Sound Stewards educational program into NYC, the restoration of the Great Meadows Marsh in Connecticut, and the ongoing work to protect and restore eelgrass populations in the Sound. The publication also includes some words from LISS program director Mark Tedesco, who shares information on the first round of projects supported by Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funds.