Judy talks pollinators with renowned authority Mary Ellen Lemay, the originator of the Pollinator Pathway project. Learn more on the iCRV website.

Connecticut Sea Grant’s Judy Preston, who is the Long Island Sound Study Outreach Coordinator for Connecticut, is on the air and on online streaming! Judy is the host of a new radio show on the iCRV internet radio station in the CT River Valley. The “Gardening for Good” show strives to make connections between good gardening practices and protecting local streams and Long Island Sound.

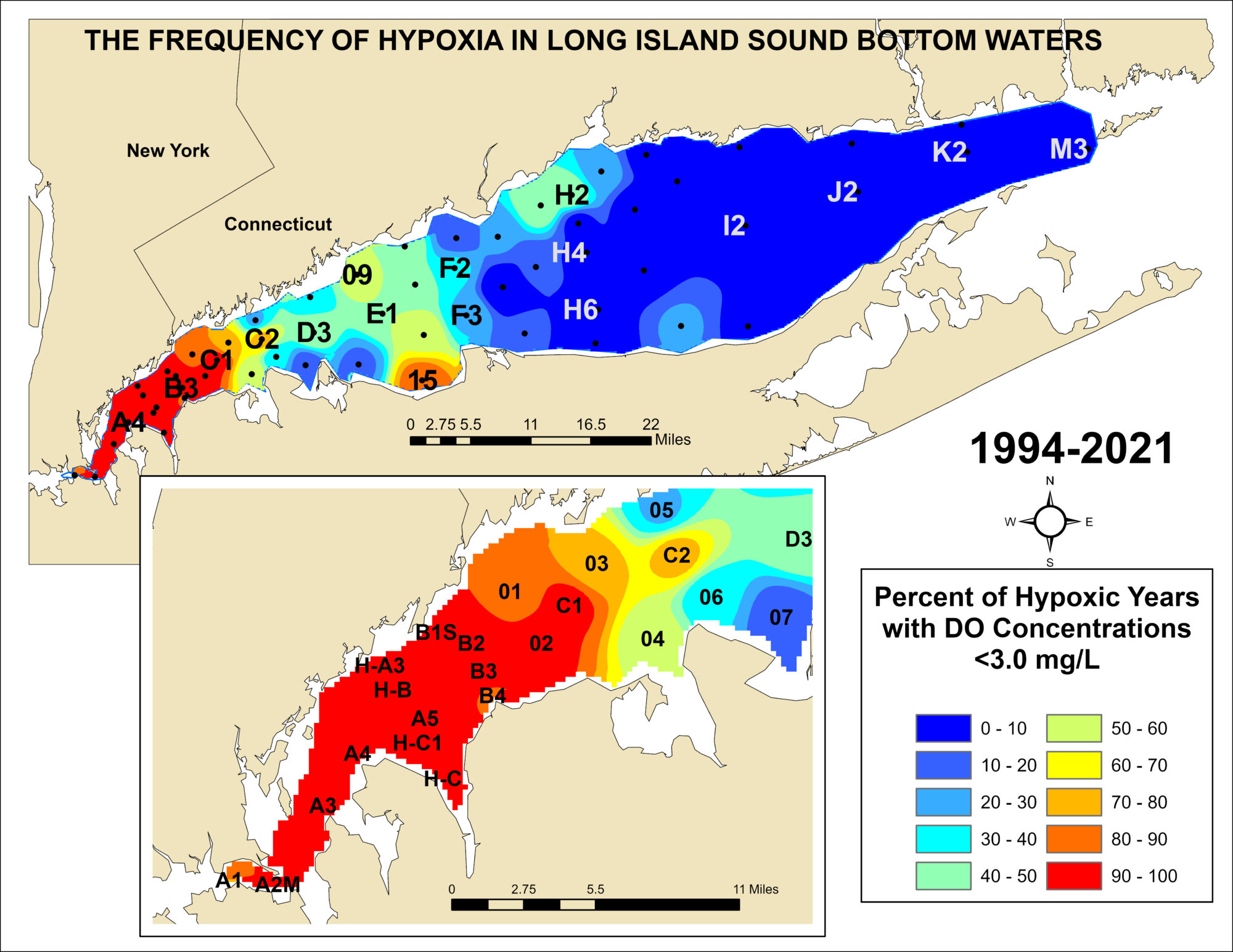

The map above illustrates the areas of Long Island Sound that are most frequently affected by hypoxia. The colors on the map represent the percentage of years in which hypoxic conditions have occurred in the bottom waters of Long Island Sound since the LISS Water Quality Monitoring program was instituted in the early 1990s.

Hypoxia is a condition that occurs in bodies of water as dissolved oxygen concentrations decrease to levels where organisms become physically stressed and ultimately cannot survive. Prolonged hypoxic conditions result in severe die-offs of animals that are unable to move out of hypoxic waters, mass migrations of mobile animals, changes in water chemistry and other adverse ecological effects. The Long Island Sound Study defines hypoxia as waters with dissolved oxygen concentrations less than 3 mg/L.

The bottom waters in the westernmost areas of Long Island Sound have experienced hypoxia virtually every year since monitoring began. Another area of regular hypoxic conditions is Smithtown Bay in Long Island (station 15).

The series highlights different Long Island Sound Study initiatives to help accomplish goals established in the Long Island Sound Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan.

- Restoring Long Island Sound: Snapshot 2021

- Restoring the Sound’s Coastal Habitats

- Restoring Migratory Fish Passage

- Long Island Sound Research

- A Healthier Long Island Sound: Nitrogen Pollution

- Long Island Sound Futures Fund (NFWF)

Sugar kelp is a cold-weather brown algal species of seaweed that grows in the winter and is harvested in spring. It also is being tested this year in three bioextraction projects to investigate if seaweed can be cultivated in Long Island Sound and other regional waters to improve water quality. Sugar kelp is useful as a ‘bioextractor’ in urban waters. Kelp extracts excess nutrients, such as nitrogen, from the water column and stores it in its tissues so there is less nitrogen available for spring algal blooms, which in excess can harm the Sound’s water quality. By harvesting the kelp in the springtime, the nutrients that cause excess algae growth are also removed.

This winter, three projects involving kelp farming that are also nutrient bioextraction pilot projects are taking place in Long Island and Connecticut waters. Two of those pilot projects, with funding provided in part by the Long Island Sound Futures Fund, are located in Long Island Sound. The third project is located in Long Island Bays (Great South Bay and Reynold’s Channel) and is being funded in part by the Long Island Community Foundation. Nelle D’Aversa, the Long Island Sound Bioextraction Coordinator, is providing technical expertise. Information on the three projects is available in the bioextraction web pages on the Long Island Sound Study website.

Home page photo: Sixto Portilla, owner of Open Water Enterprises, LLC, seeds long lines with juvenile sugar kelp at part of a nutrient bioextraction pilot study supported by the LISS Bioextraction Coordinator. Portilla is an experienced commercial shellfish grower who is interested in diversifying into seaweed aquaculture.

This article, a news release from Dec. 16, 2019, was written and distributed by Save the Sound, which is partnering with New York State to restore wetlands at Sunken Meadow State Park, a Long Island Sound Stewardship site in Kings Park, New York.

Restoration of 135 Acres of Salt Marsh Span More than 7 years

Save the Sound and the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (NYS Parks) have completed the final phase of improvements designed to restore and protect 135 acres of salt marsh in Sunken Meadow State Park, which is visited by more than 3 million New Yorkers a year. The project was laid out in the Sunken Meadow Comprehensive Resilience and Restoration Plan, a multi-million-dollar effort to restore the park’s long-compromised marsh ecosystem and enhance its ability to deal with coastal storms.

“This project broke new ground for us as an organization, and for restoration practices in the region,” said Gwen Macdonald, director of ecological restoration for Save the Sound. “This was a complex endeavor that required close cross-sector collaboration over many years to ensure that our interventions were appropriate to encourage restoration of this threatened ecosystem. The way Sunken Meadow Creek and the salt marsh have responded is a testament to the resilience of nature and the impact that competent, decisive, unified action can have on the ability of natural systems to restore themselves.”

In addition to continuing efforts to control the invasive Phragmites australis reed and restore native grasses to dominance, the final phase of work included the retrofit of 16.6 acres of a parking lot with green infrastructure (GI). These improvements included two constructed wetlands, eight bioswales, and several tree filter strips—totaling about 8.6 acres of permeable, green infrastructure that will capture and treat approximately 8.5 million gallons of stormwater each year. The entire parking area (known as Field 2) is now under Best Management Practices for stormwater.

Sunken Meadow Creek and adjoining saltwater wetlands were cut off from the tidal flow of Long Island Sound in the 1950s by a man-made barrier, turning the area into a freshwater marsh. This caused marsh die-off while drastically altering its ecosystem and species composition. After Hurricane Sandy breached the barrier and re-opened the channel to saltwater flow in 2012, Save the Sound began work to aid the marsh in its recovery, with support from federal grants.

Since then, more than 4.3 acres of marsh have been directly restored by engaging hundreds of volunteers in planting native grasses at carefully chosen places throughout the marsh, and/or regrading certain areas to create better habitat for those grasses. The parking lot retrofits will help to protect the restored marsh from harmful pollutants as native species return and begin to thrive.

Now that the parking lot transformation is complete, there is only one thing left to do— celebrate. NYS Parks will be installing educational signage around the Field 2 parking area ahead of a celebratory event next spring.

Meanwhile, Save the Sound is looking ahead to the next project in the area. Where Sunken Meadow Creek meets Long Island Sound, it also meets the mouth of the Nissequogue River. A little way upstream on that river, the Phillips Millpond Dam blocks the passage of migratory fish. In the coming months, many of the same partners from the Sunken Meadow State Park project will begin work on a project to restore access to spawning habitat upstream of that dam.

Funding for the Sunken Meadow State Park restoration project was provided by the U.S. Department of the Interior and administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation as part of the Hurricane Sandy Coastal Resiliency Competitive Grant Program, with additional funding provided by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

#

More information on the Sunken Meadow Comprehensive Resilience and Restoration Plan:

https://greencitiesbluewaters.wordpress.com/2015/02/09/resiliency-restorationat-

sunken-meadow-park/

https://greencitiesbluewaters.wordpress.com/2015/02/13/resiliency-restorationat-

sunken-meadow-park-part-ii/

- https://greencitiesbluewaters.wordpress.com/2015/02/09/resiliency-restorationat- sunken-meadow-park/

- https://greencitiesbluewaters.wordpress.com/2015/02/13/resiliency-restorationat- sunken-meadow-park-part-ii/

The April 28-29th workshop to learn how to develop effective environmental campaigns using Community-Based Social Marketing techniques was postponed because of the coronavirus outbreak. The Long Island Sound Study is looking forward to rescheduling the event soon.

Contact: Robert Burg, LISS Communications Coordinator

Phone: 203-977-1546/email: cbsm@longislandsoundstudy.net

Web: www.longislandsoundstudy.net

Stamford, CT, Feb. 18, 2020—Registration has opened today for an educational workshop targeted to environmental managers and advocates of Long Island Sound and its rivers and streams. The spring training focuses on developing effective environmental behavior change campaigns.

The two-day workshop, which will be held at the Beardsley Zoo in Bridgeport, is being led by Dr. Doug McKenzie-Mohr, an internationally known environmental psychologist. Dr. McKenzie-Mohr will explain the steps to conduct Community-Based Social Marketing (CBSM), a method that incorporates scientific knowledge on behavior change into the design and delivery of locally-based outreach campaigns. Attendees will learn how to select the most impactful behaviors, identify the barriers and benefits to change, pilot-test a campaign, and make improvements for broad-scale implementation. Lessons will be based on numerous case studies illustrating CBSM’s use. More than 75,000 program managers have attended Dr. McKenzie-Mohr’s workshops throughout North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. This will be his first in the Long Island Sound region.

Traditional environmental campaigns rely on information to try to persuade people to change their behaviors, such as providing a brochure explaining how over-fertilizing a lawn can lead to poor water quality.

“There is a lot of evidence that providing information by itself is not enough to motivate people to improve their environmental practices,” said Holly Drinkuth, co-chair of the Long Island Sound Citizens Advisory Committee and Director of Outreach and Watershed Projects for The Nature Conservancy in Connecticut. “We are excited that Dr. McKenzie-Mohr will be here to take us through the steps that lead to successful campaigns and meaningful change.”

“A CBSM pilot project conducted in the Niantic River watershed, led by the Long Island Sound Study in partnership with The Nature Conservancy and the Niantic River Watershed Committee, demonstrated that people are willing to change behaviors when they are asked to by a trusted local entity,” said Judy Rondeau, coordinator for the Niantic River Watershed Committee and Assistant Director of the Eastern Connecticut Conservation District. “Over 70 percent of homeowners agreed in the pilot to participate in our campaign, which encouraged homeowners to reduce or eliminate the use of lawn fertilizer.”

Workshop Details

Date: April 28-29, 2020

Location: Hanson Exploration Station, Beardsley Zoo, 1875 Noble Ave., Bridgeport, CT

Registration: $75 (Feb. 18-April 6); $95 (April 7-April 17). Registration closes on April 17 at midnight, or when capacity is reached.

A link to register is below, or find it on the Long Island Sound Study workshop web page (at www.longislandsoundstudy.net) where you can also find more information about the workshop, including an agenda and a biography of Dr. McKenzie-Mohr.

Attendance is limited to participants who work for organizations in the Long Island Sound watershed from CT and NY. If you work outside the region, please contact Audra Martin at amartin@neiwpcc.org before completing your registration.

REGISTER HERE

The Long Island Sound Study is pleased to offer this workshop at a reduced rate. Early registration is recommended as only 50 seats are available.

The Long Island Sound Study is a multi-jurisdictional ecosystem-based management program that works with federal, state, and local partners to restore and protect Long Island Sound. NEIWPCC, with support from The Nature Conservancy-Connecticut and the Eastern Connecticut Conservation District, is organizing the workshop.

This project has been funded wholly or in part by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under assistance agreement LI-00A00384 to NEIWPCC. The contents of this workshop do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the EPA, nor does the EPA endorse trade names or recommend the use of commercial products mentioned in relation to this workshop.

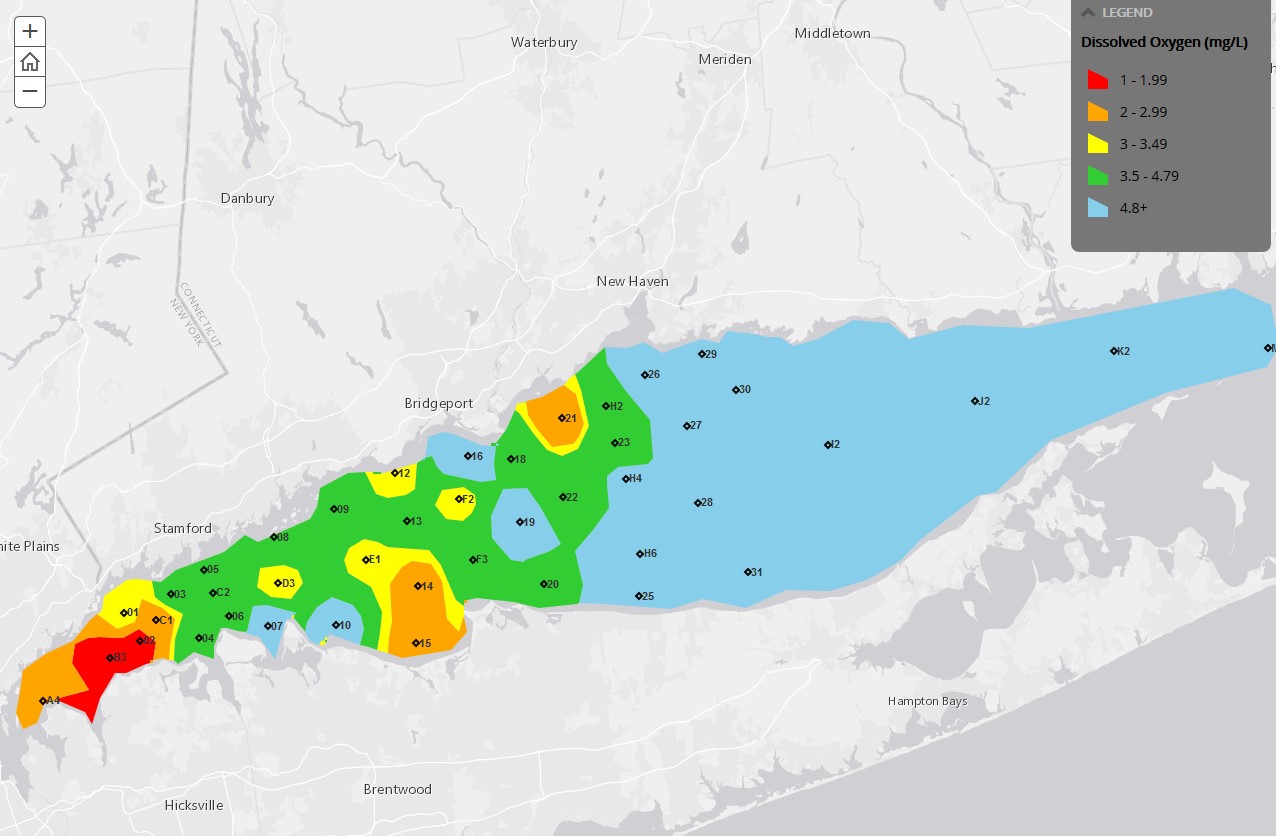

Throughout most of the year wind and tidal mixing bring much needed dissolved oxygen to the Sound’s bottom waters. However, rising summer temperatures coupled with increased respiration from microbes (a consequence of excess nitrogen in the water) can deplete the bottom layer, resulting in summer hypoxia (dissolved oxygen levels below 3 mg/L). The increasing temperatures also limit the diffusion of oxygen to the bottom waters and the amount of oxygen the bottom layer can hold. The resulting hypoxia stresses fish and other wildlife. Toward the late summer, when temperatures start to cool and winds mix the surface and bottom waters, oxygen levels rebound. Open the story map prepared by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection to see a time series of monthly changes to the oxygen levels of the Sound in 2014.

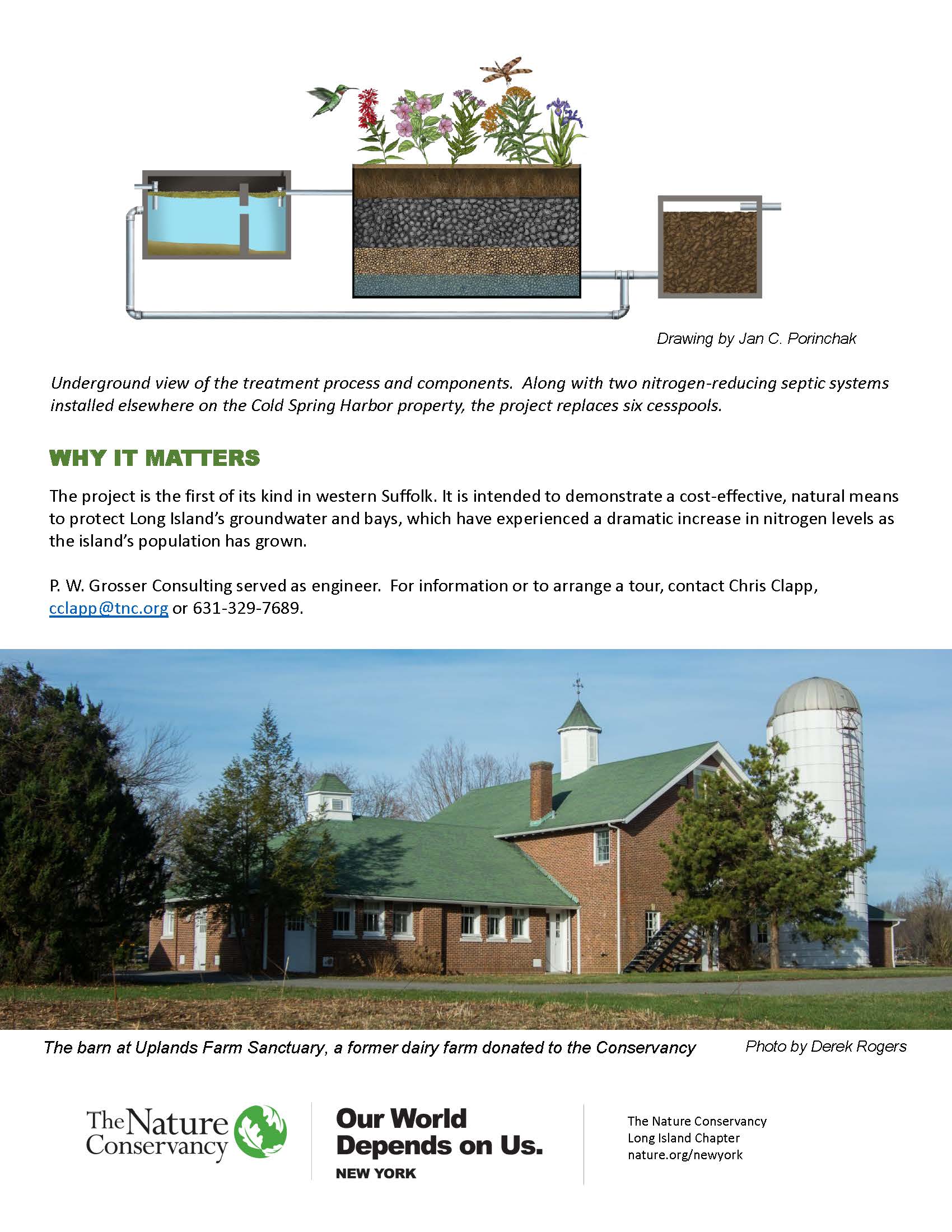

Building a Wetland to Capture Nitrogen and Improve Water Quality

A nitrogen-reducing wetland has replaced decades-old cesspools at the office and residential complex at The Nature Conservancy’s Uplands Farm Sanctuary in Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island. The plant-based wastewater treatment system will convert harmful nitrogen in raw wastewater into a harmless gas. Nitrogen pollution is to blame for numerous water quality issues on Long Island including harmful algal blooms that kill fish and make it unsafe to use affected ponds and lakes for recreation and shellfishing. Watch the video to see how it was done. To learn more, read a description of the project from TNC’s Long Island Sound Futures Fund award or read a fact sheet.

Project: Demonstrating Onsite Wastewater Treatment Systems for Clean Water at Uplands Farm Sanctuary

Grantee: The Nature Conservancy, Long Island

The Nature Conservancy, Long Island will construct and publicize the results of the first nitrogen-reducing vegetated wastewater treatment system in Cold Spring Harbor, Suffolk County, New York. The project demonstrates a system that treats wastewater in a natural manner, reduces nitrogen discharges, and safely removes pathogens providing an alternative to traditional waste treatment in cesspools which contributes nitrogen and other pollutants into Long Island Sound. The project will install a vegetated wastewater treatment system at an office and residential complex in Cold Spring Harbor, and publicize this attractive, plant-based treatment method in Suffolk County, New York. Excess nitrogen is a threat to the health of Long Island Sound. A Nitrogen Loading Model assessment found that nitrogen from septic systems/cesspools is the major land-based source of nitrogen in 12 of 13 Sound watersheds from Little Neck Bay to Northport Bay, including the Cold Spring Harbor watershed where Uplands Farm is located. The project will: 1) sample soil and groundwater pre-construction to assess the quantity of nitrogen leaving the current cesspools and determine baseline levels in the area where the new system will be located; 2) Sample post-construction to determine nitrogen reduction; and 3) install a hybrid moving bed bio-reactor and a constructed wetland using native plants to handle follows of 1,000 gallons per day. The system size can be adjusted to adapt to larger-flow homes, clusters of homes, or offices. The plantings provide botanical for nitrification, which will be followed by de-nitrification. A drain field for effluent will further absorb nitrogen; and 4) publicize through site visits, signage, short videos, social and traditional media, and conference presentations. The project will reduce nitrogen in the effluent to nearly zero, and by at least 90 percent resulting in a reduction of at least 150 pounds of nitrogen annually.

iCRV internet radio owner Dave Williams introduces LISS Outreach Coordinator Judy Preston as the host for the station’s new Gardening for Good show. Judy gives an overview of all she will cover in her new program and the resources available to advanced and beginning gardeners. Judy also talks about the role of the Long Island Sound Study and Connecticut Sea Grant in helping to protect Long Island Sound.

Connecticut Sea Grant’s Judy Preston, who is the Long Island Sound Study Outreach Coordinator for Connecticut, is on the air and on online streaming! Judy is the host of a new radio show on the iCRV internet radio station in the CT River Valley. The “Gardening for Good” show strives to make connections between good gardening practices and protecting local streams and Long Island Sound.

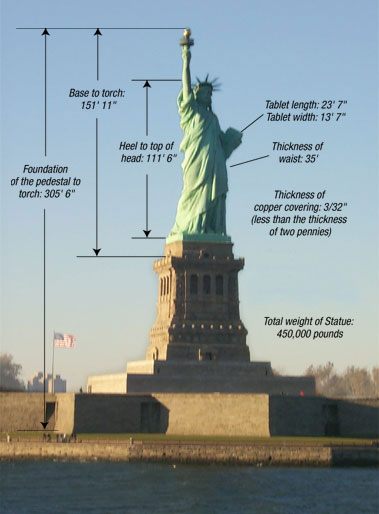

The average depth of Long Island Sound is a shallow 63 feet. If dropped into the Sound at this depth, the Statue of Liberty would still have 86 feet exposed above the water (not including the pedestal).

Why do we say that’s shallow? It’s shallow compared to the average depth of the Atlantic Ocean. It has an average depth, with its seas, of 10,925 feet (3,300 meters) and a maximum depth of 27,493 feet (8,380 meters) in the Puerto Rico Trench, north of the island of Puerto Rico. The Hudson Canyon, a submarine canyon, which runs from the Hudson River- New York/New Jersey Harbor to 400 nautical miles offshore, reaching depths of 3,500 meters (10,500 feet). Source: Marine Conservation Institute.

The depths of the Sound vary greatly by location. In the western Sound, with its smooth sandy seafloor, the depths can be well under 20 feet. In the central Sound, it’s around 65 feet, while the eastern Sound is deep, dipping to 350 feet at the Race with a bottom that is mostly rocky.

The height of the Statue of Liberty is 305′ 6″ from the foundation of the pedestal to the torch, but it is 151′ 11″ from the base to the torch. Source: Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation

The Sound Facts series is adapted from Sound Facts: Fun Facts About Long Island Sound, a Connecticut Sea Grant publication.